First patient-derived stem cell model for studying eye conditions related to oculocutaneous albinism developed by the National Eye Institute

Lead author of the report, Doctor Aman George from the National Eye Institute (NEI) stated that “this ‘disease-in-a-dish’ system will help us understand how the absence of pigment in albinism leads to abnormal development of the retina, optic nerve fibres, and other eye structures crucial for central vision,”

What is Oculocutaneous albinism?

Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA), is a set of genetic conditions that affects pigmentation in the eye, skin, and hair due to mutation in the genes crucial to melanin pigment production.

Oculocutaneous albinism reduces pigmentation of the coloured part of the eye known as the iris and the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye known as the retina. People with this condition usually have vision problems including: reduced sharpness, rapid, involuntary eye movements and increased sensitivity to light.

People with OCA lack pigmented retinal pigment epithelium (RPE),and have an underdeveloped fovea, an area within the retina that is crucial for central vision. The optic nerve carries visual signals to the brain.

People with OCA have misrouted optic nerve fibres. Scientists think that RPE plays a role in forming these structures and want to understand how lack of pigment affects their development.

How did the team create their model?

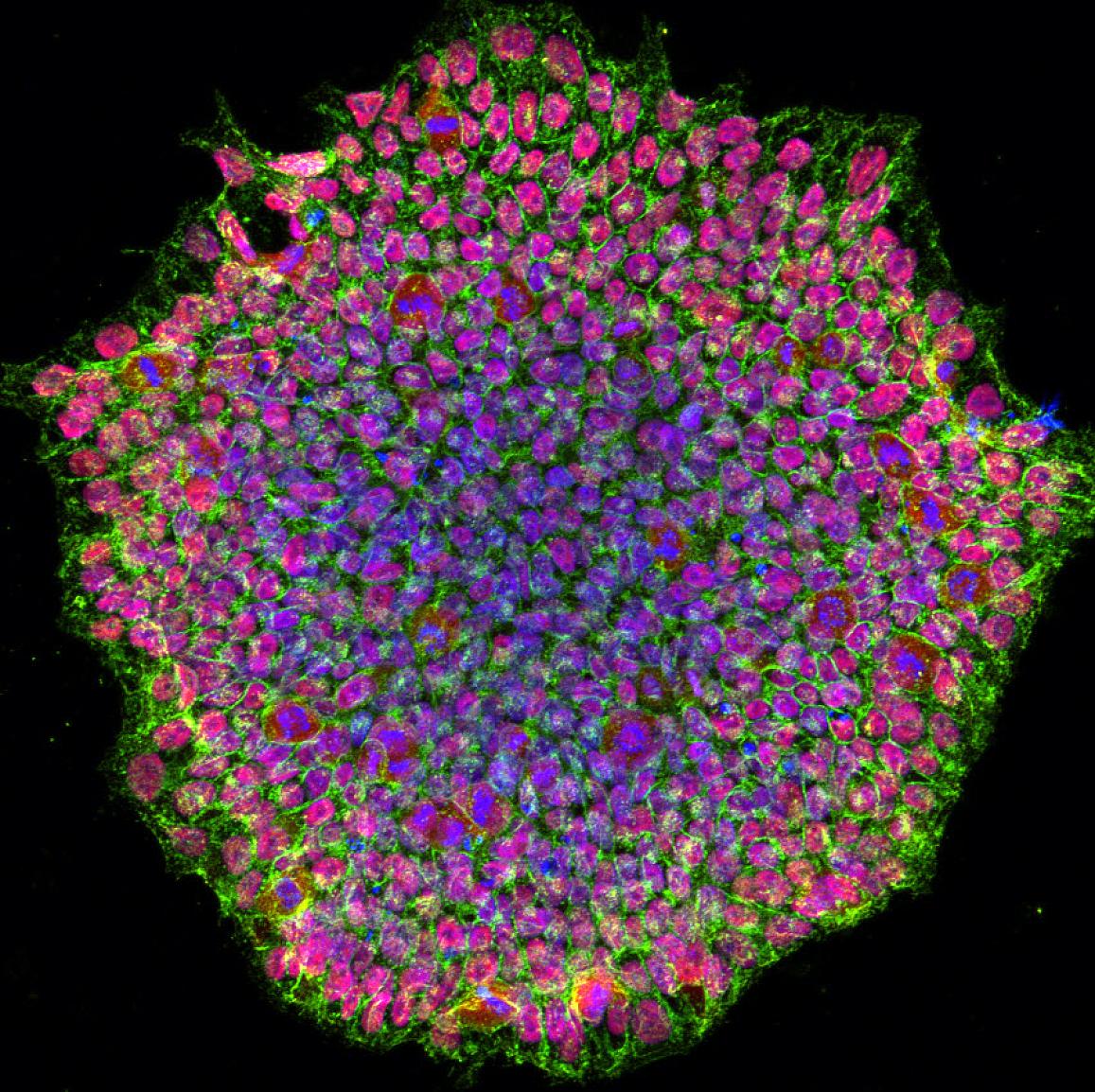

Researchers reprogrammed skin cells from individuals without OCA and people with the two most common types of OCA, into pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The iPSCs were then differentiated to retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells. The RPE cells from patients were identical to RPE cells from unaffected individuals but displayed significantly reduced pigmentation.

Following this, the researchers will use their model to study how a lack of pigmentation affects RPE physiology and function.

In theory, if fovea development (a tiny pit located in the macula of the retina that provides clear vision) is dependent on RPE pigmentation, and pigmentation can be somehow improved, vision defects associated with abnormal fovea development could be at least partially resolved, according to Doctor P. Brooks, NEI clinical director and chief of the Ophthalmic Genetics and Visual Function Branch.

“Treating albinism at a very young age, perhaps even prenatally, when the eye’s structures are forming, would have the greatest chance of rescuing vision,” said Brooks. “In adults, benefits might be limited to improvements in photosensitivity, for example, but children may see more dramatic effects.”