The Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester have been shedding light on how healthy brains multitask while walking

Using an MoBI – Mobile Brain/Body imagine system – the team combined virtual reality, brain monitoring and motion capture technology in order to monitor the ways in which participants brain activity changed.

“This research shows us that the brain is flexible and can take on additional burdens,” said David Richardson, an MD/PhD student in the Pathology & Cell Biology of Disease Program, and first author of the study.

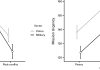

“Our findings showed that the walking patterns of the participants improved when they performed a cognitive task at the same time, suggesting they were actually more stable while walking and performing the task than when they were solely focused on walking.”

While participants walk on a treadmill or manipulate objects on a table, 16 high speed cameras record the position markers with millimetre precision, while simultaneously measuring their brain activity.

Neurophysiological differences

The MoBI system was used to record the changing brain activity of participants as they walked on a treadmill and were instructed on tasks to complete. To compare the ways in which the brain dealt with multitasking – the participants were also closely motioned whilst conducting the same tasks while sitting.

The results were able to show the neurophysiological differences between the easy and difficult tasks when both walking and sitting. Researchers highlighted the flexibility of a healthy brain and how it prepares for and executes tasks dependant on the level of difficulty involved.

What is the future for this research?

“The MoBI allows us to better understand how the brain functions in everyday life,” said Dr Edward Freedman, lead author on the study.

“Looking at these findings to understand how a young healthy brain is able to switch tasks will give us better insight to what’s going awry in a brain with a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s disease.”

Researchers are hoping to expand their work and undergo the same study on a more diverse group of brains.

“Understanding how a young healthy brain can successfully ‘walk and talk’ is an important start, but we also need to understand how these findings differ in the brains of healthy older adults, and adults with neurodegenerative diseases,” said Richardson.