Maxine Smeaton, Chief Executive of Epilepsy Research UK delves into the common yet complex connections between brain tumours and seizures

It is a common misconception that epilepsy is solely an inherited genetic condition. The truth is that in roughly 65% of cases, though epilepsy may be a dominant part of someone’s life, the underlying cause remains unknown.

What we do know is that anyone can acquire epilepsy, either through other medical conditions, head injury or changes in the structure of the brain, such as those caused by a brain tumour.

Seizures occur when electrical activity in the brain becomes unregulated and a burst of abnormal signals in one or more regions of the brain interrupt normal signals. It can be useful to think of seizures as a warning system and an indicator that something may be wrong in the brain. Like the pain we feel when burning our hand, in some cases, seizures are an indication of overall brain health.

The link between brain tumours and seizures

As many as two in three people diagnosed with a brain tumour will experience seizures. The nature and severity of these seizures will vary from person to person, depending on the region of the brain that is affected. Patients often report their seizures as one of the most debilitating symptoms of their brain tumour, having a big impact on their quality of life.

Unfortunately, seizures linked to brain tumours can be difficult to treat. Surgery remains the most common method for treating brain tumours, however, surgery to treat seizures themselves is limited because there are few reliable ways of locating where exactly in the brain they originate from.

Types of brain tumours called gliomas are known to increase the chances of a person developing epilepsy. The surgical treatment for epilepsy is the same as for the tumour – remove the part of the brain that’s causing the problems. However, finding the tissue around the tumour that is causing seizures can be difficult and highly invasive, posing other risks to brain health.

Pioneering approaches in surgery

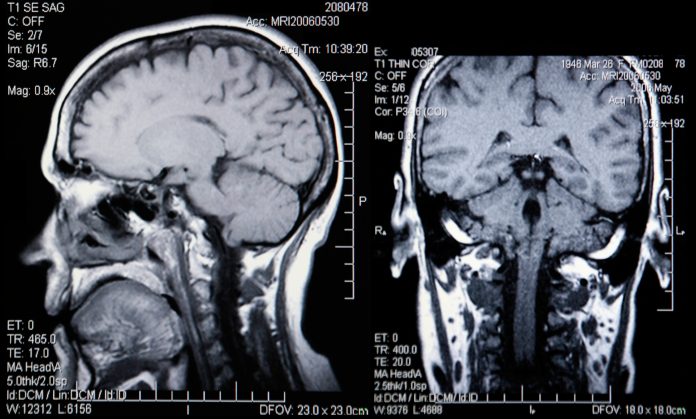

Epilepsy Research UK Emerging Leader Fellow and trainee neurosurgeon Mr Ashan Jayasekera has pioneered a new surgical method used to treat seizures in patients with brain tumours. Based at Newcastle University, Ashan’s research developed a non-invasive technique using MRI scans to pinpoint which parts of the brain tissue need to be removed to halt seizures, while causing minimal disruption to the rest of the brain.

Ashan said one of the things he found most notable when starting to treat patients with brain tumours was how affected they were by their seizures. “Seizures are very common in patients with a particular kind of brain tumour called a glioma, and they are often very difficult to treat, as well as having the biggest bearing on quality of life. The aim of treating gliomas has often been centred on trying to safely remove as much of the tumour as is possible, without injuring surrounding healthy brain to try and extend life.”

However, removing the tumour may not necessarily prevent seizures as they do not start in the tumour – they originate in the part of the brain next to the tumour. Ashan explains, “This poses a problem to the surgeon: which bits of the surrounding brain should they remove to render a patient seizure-free? How much do they need to remove? Traditionally surgeons have worked in conjunction with neurophysiologists to map the areas of seizure generating brain, by placing grids of electrodes around tumours and looking for any abnormal electrical activity. However, doing this involves another operation that carries risks and it’s not yet clear how effective this method is.”

“This is where my research – very generously funded by an Epilepsy Research UK Emerging Leader Fellowship Award – comes in. I wanted to demonstrate that areas of the brain around a tumour with high levels of glutamate could be responsible for generating seizures. As part of the research, patients would have MR spectroscopy scans prior to their surgery, and a sample of tissue would be taken to the lab to look for any spontaneous seizure activity.”

Through this project, Ashan discovered that tissue that had been connected to spontaneous seizures came from areas of the brain around a tumour with high glutamate levels. This is the first time this has been demonstrated in the lab and is an important step towards showing that MR spectroscopy could be used in mapping the areas of the brain responsible for seizures in patients with gliomas.

Ashan stated, “I am grateful to the hardworking and generous supporters of Epilepsy Research UK for funding this important area of research and me as an aspiring clinical academic. Working with patients who give up their time so generously to be part of research is an ongoing privilege and the driving force for me personally to carry on this work.”

As a charity, it is a privilege to fund research such as Ashan’s, which could lead to successful surgeries for more patients, resulting in more lives free from epilepsy and the interruptions caused by seizures.