Dr Gerard Sinovich, Lead Pain Specialist, provides an in-depth commentary on behalf of Cantourage Clinic concerning what we need to know about opioids and opioid dependence

Opioids are highly addictive, in large part because they activate powerful reward centres in your brain. Opioids trigger the release of endorphins, your brain’s feel-good neurotransmitters. Endorphins muffle your perception of pain and boost feelings of pleasure, creating a temporary but powerful sense of well-being, which can easily lead a person to opioid dependence.

Opioids have been regarded for millennia as among the most effective drugs for the treatment of pain. Their use in the management of acute severe pain and chronic pain related to advanced medical illness is considered the standard of care in most of the world. In contrast, the long-term administration of an opioid for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain continues to be controversial. Concerns related to effectiveness, safety, and abuse liability have evolved over decades, sometimes driving a more restrictive perspective and sometimes leading to a greater willingness to endorse this treatment. The past several decades in the United States have been characterised by attitudes that have shifted repeatedly in response to clinical and epidemiological observations and events in the legal and regulatory communities. The interface between the legitimate medical use of opioids to provide analgesia and the phenomena associated with abuse and addiction continues to challenge the clinical community, leading to uncertainty about the appropriate role of these drugs in treating pain.

How do people fall into opioid dependence?

Opioid dependence develops after a period of regular use of opioids, with the time required varying according to the quantity, frequency and route of administration, factors of individual vulnerability and the context in which drug use occurs.

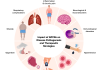

Physical and psychological dependence can develop within a relatively short period of continuous use (2-10 days). Brain abnormalities resulting from chronic use of heroin, oxycodone, and other morphine-derived drugs are underlying causes of opioid dependence (the need to keep taking drugs to avoid a withdrawal syndrome) and addiction (intense drug craving and compulsive use). The abnormalities that produce dependence, well understood by science, appear to resolve after detoxification, within days or weeks after opioid use stops. However, the abnormalities that produce addiction are more wide-ranging, complex, and long-lasting. They may involve an interaction of environmental effects – for example, stress, the social context of initial opiate use, and psychological conditioning – and a genetic predisposition in the form of brain pathways that were abnormal even before the first dose of opioid was taken. Such abnormalities can produce craving that leads to relapse months or years after the individual is no longer opioid dependent.

There are several risk factors for opioid dependence

- Having an opioid use disorder.

- Taking opioids by injection.

- Resumption of opioid use after an extended period of abstinence (e.g., following detoxification, release from incarceration, cessation of treatment).

- Using prescription opioids without medical supervision.

- High prescribed dosage of opioids (more than 100 mg of morphine or equivalent daily).

- Using opioids in combination with alcohol and/or other substances or medicines that suppress respiratory function, such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, anaesthetics or some pain medications; and

- Having concurrent medical conditions such as HIV, liver or lung diseases or mental health conditions.

Males, people of older age and people with low socio-economic status are at higher risk of opioid dependence than women, people of young age groups and people with higher socio-economic status.

Opioid-based medicine for pain treatment

Regarding pain treatment, opioid-based medicine is still the standard course of care, and opioids can arguably provide life-saving relief for patients. But opioid misuse and dependency is a debilitating problem, with opioid use disorder affecting more than 16 million people worldwide. In England, opioid prescriptions increased by 128% since 1998, and opiates were involved in almost half (2,219) of drug-poisoning deaths in England and Wales during 2021.

The number of opioid overdoses has also increased in recent years in several other countries, in part due to the increased use of opioids in the management of chronic pain and the increasing use of highly potent opioids appearing on the illicit drug market. In the United States of America (U.S.), the number of people dying from opioid overdose increased by 120% between 2010 and 2018, and two-thirds of opioid-related overdose deaths in 2018 in the U.S. involved synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and its analogues. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a further substantial increase in drug overdose deaths was reported in the U.S., primarily driven by rapid increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids.

Measures to prevent opioid dependence

Beyond approaches to reducing drug use in general in the community, there are specific measures to prevent opioid dependence and overdose. These include:

- Increasing the availability of opioid dependence treatment, including for those dependent on prescription opioids.

- Reducing and preventing irrational or inappropriate opioid prescribing.

- Monitoring opioid prescribing and dispensing; and

- Limiting inappropriate over-the-counter sales of opioids.

The gap between recommendations and practice is significant. Only half of the countries provide access to effective treatment options for opioid dependence and less than 10% of people worldwide in need of such treatment are receiving it.

Opioid tolerance, dependence, and addiction are all manifestations of brain changes resulting from chronic opioid abuse. The opioid abuser’s struggle for recovery is in great part a struggle to overcome the effects of these changes. Medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone act on the same brain structures and processes as addictive opioids but with protective or normalising effects. Despite the effectiveness of medications, they must be used in conjunction with appropriate psychosocial treatments.

Given the over-prescription of opioid-based pain management across traditional medicine and the (arguably) related opioid epidemic that is devastating communities around the world, medical cannabis could provide an alternative to opioid-based pathways and be used as a treatment for those struggling with addiction and substance use disorders.

Medical cannabis as an adjunct to opiates

Medical cannabis is currently being used as an adjunct to opiates, given its analgesic effects and potential to reduce opiate addiction. This review assessed if medical cannabis used in combination with opioids to treat non-cancer chronic pain would reduce opioid dosage.

Study eligibility included randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and case reports.

Nine studies involving 7,222 participants were included. There was a 64-75% reduction in opioid dosage when used in combination with medical cannabis. The use of medical cannabis for opioid substitution was reported by 32–59.3% of patients with non-cancer chronic pain.

As with a lot of real-world evidence coming out about medical cannabis, the optimal medical cannabis dosage to achieve opioid dosage reduction remains unknown. Therefore, more research is needed to elucidate whether medical cannabis used in combination with opioids in treating non-cancer chronic pain is associated with health consequences that are yet unknown.

According to two studies recently published in JAMAInternal Medicine, the rate of opiate prescriptions is lower in states where medical cannabis laws have been passed.

One of the studies, a longitudinal analysis of the number of opioid prescriptions filed under Medicare Part D, showed that when medical cannabis laws went into effect in a given state, opioid prescriptions fell by 2.21 million daily doses filled per year. When medical cannabis dispensaries opened, prescriptions for opioids fell by 3.74 million daily doses per year. These reductions in daily opioid doses were particularly notable for hydrocodone (Vicodin) and morphine prescriptions.

The other study analysed Medicaid prescription data from 2011 to 2016, and that analysis showed that states that have implemented medical cannabis laws have seen a 5.88% lower rate of opioid prescribing.

A 2014 study, also published in JAMA, showed that “states with medical cannabis laws had a 24.8% lower mean annual opioid overdose mortality rate…compared with states without medical cannabis laws.” The fact that opioid overdose deaths appear to be falling in states with medical cannabis laws complements this new research that suggests that fewer opiates are being prescribed.

References

1. WHO (2019). International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Eleventh Revision.

2. UNODC (2021). World Drug Report 2021. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/wdr2021.html

3. CDC WONDER (2020). National Centre on Health Statistics

4. CDC Emergency Preparedness and Response: Increase in Fatal Drug Overdoses Across the United States Driven by Synthetic Opioids Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic, 17 December 2020. Available at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00438.asp

5. Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Evans-Lacko S, et al. (2017). Estimating treatment coverage for people with substance use disorders: an analysis of data from the World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):299-307. doi:10.1002/wps.2045

6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7388229/

7. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/access-to-medical-marijuana-reduces-opioid-prescriptions-2018050914509