Mice offer valuable insights into the mysterious world of daydreams and their potential impact on brain plasticity

The study led by researchers at Harvard Medical School, published in Nature on December 13, looks into the activity of neurons in the visual cortex. Revealing connections between daydreaming and the brain’s ability to reshape itself.

In the past, scientists have focused on the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped brain region crucial for memory and spatial navigation, to understand how neurons replay past events.

However, attention has shifted to the visual cortex’s role in forming visual memories. The research team, led by Nghia Nguyen, a PhD student in neurobiology at HMS, and senior author Mark Andermann, Professor of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, explored this brain region.

The cause of daydreaming

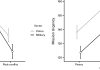

The study repeatedly showed mice two distinct checkerboard patterns, monitoring the firing patterns of around 7,000 neurons in the visual cortex. When the mice looked at an image, neurons fired in a specific pattern.

The discovery came when mice were relaxed, showing similar, not identical, firing patterns as a sign of daydreaming. These daydreams were more frequent at the beginning of the day and correlated with calm behaviour and small pupils.

Representational drift

The researchers noticed the “representational drift” observed in the neurons’ activity patterns throughout the day. The brain’s response to the same image changed, and early daydreams predicted this shift. This suggests that daydreams may actively participate in brain plasticity. Steering neural patterns associated with different images away from each other.

Nguyen explained, “Our findings suggest that daydreaming may guide this process by steering the neural patterns associated with the two images away from each other,” indicating that discerning between images improves with daydreaming, enhancing specificity in future responses.

The study revealed a synchronised activity between the visual cortex and the hippocampus during daydreams, indicating communication between these brain regions. This raises the possibility that daydreams shape the brain’s response to visual stimuli.

The potential parallels in the human brain

The study’s implications extend beyond mice, with potential parallels in human brain activity during visual imagery recall. Previous research by Randy Buckner at Harvard University showcased increased visual cortex activity when humans recalled detailed images.

While these findings open new avenues for understanding daydreams and their role in brain plasticity, the researchers emphasise the need for further confirmation. “There’s so much richness in the visual cortex that nobody knew anything about,” Andermann noted.

“If you never give yourself any awake downtime, you’re not going to have as many of these daydream events”

In a world saturated with constant stimuli, the researchers suggest the importance of quiet wakefulness, advocating for moments of daydreaming to boost brain plasticity potentially. Andermann stated, “If you never give yourself any awake downtime, you’re not going to have as many of these daydream events, which may be important for brain plasticity.”

As the study marks a significant step forward, future research will delve into visual cortex neuron connections, visualising their changes when the brain encounters new images. The implications for human cognition and the potential therapeutic applications of understanding daydreaming’s role in brain plasticity remain exciting frontiers for exploration.