Do you ever find yourself wanting snacks after a full meal? According to UCLA psychologists, this might not indicate an overactive appetite but overactive food-seeking neurons in the brain

Researchers have identified a circuit in the brains of mice that drives them to seek out food, even when they’re not hungry.

Why do we feel the need to have food constantly?

Lead researcher Avishek Adhikari and his team came across these insights while investigating a brain region known as the periaqueductal grey (PAG), usually associated with panic responses rather than feeding behaviours.

However, their experiments with mice revealed that stimulation of a specific cluster of cells within the PAG, known as vgat PAG cells, triggered intense foraging and a preference for calorie-rich foods like chocolate over healthier options.

Using techniques involving light-sensitive proteins and miniature microscopes, the researchers observed how activating these neurons prompted mice to seek food, regardless of their satiety levels.

The mice were willing to endure discomfort, such as foot shocks, to indulge in fatty treats. When the activity of these cells was suppressed, the mice exhibited reduced food-seeking behaviours, even when hungry.

“The results suggest the following behavior is related more to wanting than to hunger,” Adhikari said. “Hunger is aversive, meaning that mice usually avoid feeling hungry if they can. But they seek out activation of these cells, suggesting that the circuit is not causing hunger. Instead, we think this circuit causes the craving of highly rewarding, high-caloric food.”

Understanding how the human brain thinks of food

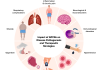

These findings hold significant importance for understanding eating disorders in humans.

Just as mice have similar vgat PAG cells, humans likely have analogous neural circuits that influence food cravings and consumption. If this circuitry is dysregulated, individuals may experience heightened cravings or diminished satisfaction from eating, potentially contributing to conditions like binge eating disorder or anorexia.

“We’re doing new experiments based on these findings and learning that these cells induce eating of fatty and sugary foods, but not of vegetables in mice, suggesting this circuit may increase eating of junk food.” remarked Fernando Reis, a postdoctoral researcher involved in the study.

The study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Science Foundation, emphasises the complex relationship between brain circuitry and behaviour. As researchers look deeper into the neural mechanisms controlling food-seeking behaviours, they hope to help develop effective treatments for individuals struggling with disordered eating.

In understanding the brain’s role in appetite regulation, this research may offer new routes for tackling the challenges of unhealthy eating and eating disorders that many people have to face daily.