Dr Mélanie Dufour-Poirier from the Université de Montréal and Dr Jean-Paul Dautel from the Université du Québec en Outaouais outline a new approach to preventing workplace mental health injuries and improving wellbeing

In Canada, it is estimated that mental health-related costs total approximately $50bn annually. In the province of Quebec, close to one out of two workers has experienced psychological distress since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Amongst its pathogens are the porosity of working time, isolation, competition among colleagues, and the demand for short-term profitability. New – more stressful – forms of work organization, including telework, have emerged, bringing with them excessive workloads, increases in the pace of work, growing job flexibility, precarious contract employment, and job insecurity. These issues have put workplace mental health back at the centre of the debate in Quebec. More generally, the crisis has called for a rethinking of management methods for better upstream protection of mental health, ideally through a collective and participatory approach that involves all the actors in a working community rather than one that aims at protecting against and treating such mental health injuries on the level of the individual, as is the current tendency. It is an issue of the utmost importance for unions, a subject we discussed in a recent article (Open Access Government, April 2024).

In light of these considerations, we have developed a research and intervention approach that is in line with the 2021 reform of Quebec’s occupational health and safety regulations. The reform now requires companies to set up prevention programmes to better protect workers’ mental wellbeing, including those working remotely. Such programmes must provide for the identification and analysis of risks that may affect mental health, measures and priorities for action to eliminate them, supervision, evaluation and follow-up measures, and the scheduling for their implementation. In addition, employers are obligated to prevent and combat any form of harassment and violence in the workplace. We believe these new legal obligations open the door to establishing a participatory process for co-constructing prevention tools based on workplace actors’ realities, insights and experiential knowledge.

The originality of our approach, compared with existing tools for identifying occupational risks or voluntary standards (limited by their undifferentiated, transversal and generic design, which does not take the specific characteristics and issues of particular workplaces into account), lies in the collaborative, developmental and capacity-building perspective fuelling it upstream. Based on the participatory paradigm, we build on the practical and experiential knowledge brought by all workplace actors at every level of a company to the identification and analysis of occupational hazards and the subsequent co-construction of a prevention programme. Because of its primary nature, truly upstream of the occurrence of mental health injuries, it is this multi-level collective intelligence supporting optimal prevention and management of them that we believe essential to marshal in workplaces. Such a philosophy is in keeping with the spirit behind the enactment in 1979 of the Act Respecting Occupational Health and Safety in Quebec, which relied upon the active, voluntary contribution of all the actors forming a working community to the design and implementation of preventive actions.

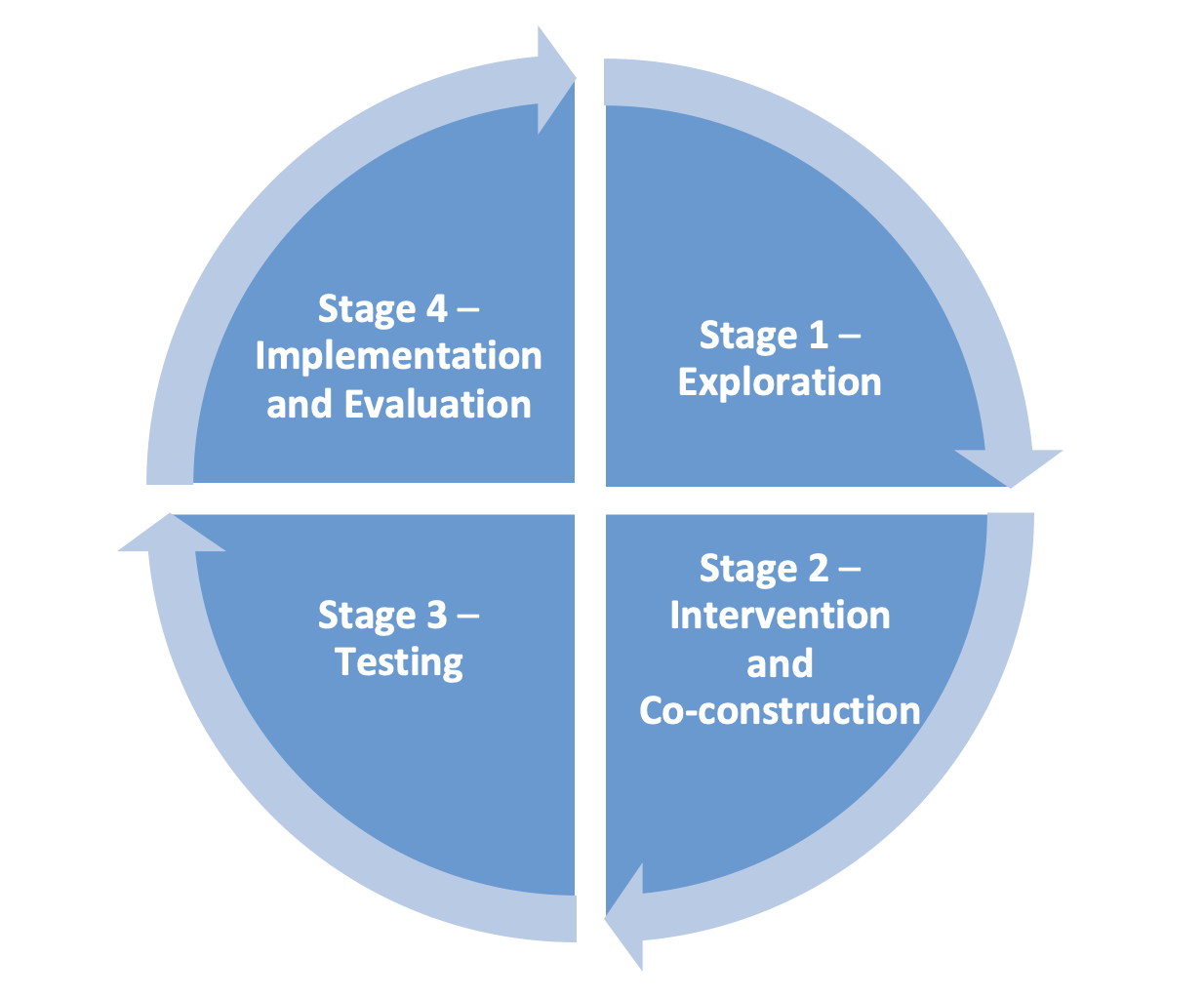

In operational terms, our ‘comprehensive and foundational’ approach—enabling an understanding and rethinking of work in order to better transform and heal it—can be broken down into four stages (see Figure 1).

- Exploration:

- The first stage involves carrying out the dual exercise of, on the one hand, understanding the work-related issues affecting workers’ mental health, which are very often connected to the design and organization of work and, on the other, cross-validating such issues with key interlocutors (employers, unions, and workers). The aim here is to create a collective and shared understanding of the current problems within the particular work setting—in short, to provide the actors involved with a common language with which to speak about them. This stage will result in a preliminary draft exploring potentially remedial, transformative actions for healing the workplace environment, which will then be tested in the field to determine their relevance and effectiveness.

- Intervention and co-construction:

- The second stage focuses on making an overall diagnosis of the issues involved by means of performing a detailed analysis of the work itself (through understanding those of its aspects that are prescribed and how they are translated into the real world of the activity) using semi- structured individual and group interviews with pre-identified key interlocutors, distributing surveys, and holding non-participant observation sessions (e.g., of meetings), to refine the understanding of the interpersonal dynamics prevailing internally. This will be followed by the co- construction of potential preventive solutions to be incorporated into an experimental protocol to test their operational capability. Key interlocutors will be brought together, on a regular and ongoing basis, in an inter-categorical monitoring committee and in working groups that have been designated for that purpose.

- Testing:

- This third stage is designed to further test the previously identified solutions. Its aim is to co-construct, together with the monitoring committee, a final version of the preventive solutions so that they can meet the legal requirements and be incorporated into a prevention programme that will be in line with the specific features of the participating workplace.

- Implementation and evaluation:

- The fourth stage consists of a final validation of the preventive solutions. It also includes the fundamental step of conducting a post-mortem of the entire process to help create a prototype for an action methodology that could potentially be replicated in other units or departments within the organization.

This approach has a number of advantages for those working in the field. Firstly, it highlights the experiential knowledge (both active and passive) of workplace actors and thus fosters more informed, collaborative, and responsive management of work-related mental health injuries. Secondly, it sparks consideration with respect to the dissemination of best practices and training measures in the area of preserving workplace mental health and primary prevention of injuries to it, notably by examining the ways in which work is performed and the relevance of the policies surrounding it.

Finally, this time, on a more general level, over and above the enormous human and economic cost that such injuries represent for employers and governments (here read absenteeism, presenteeism, and disablement), our work reiterates the importance of making mental health a positive social force for reshaping and renewing the strategies of workplace actors, and in doing so, underlines the glaring current need to turn such injuries into organizational and public health issues, wherever in the world they occur. And, as shown by the upsurge in the number and severity of mental health injuries related to it, the crisis in the workplace is, indeed, a global one.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.