Tracey Wade from Flinders University, charts an implementation approach to early intervention in eating disorders

Eating disorders are a common public health concern among youth. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the most reliable statistics tell us:

- In adolescents and emerging adults (aged 13 to 25 years), DSM-5 eating disorders affected one in six females and one in 40 males.

- In females, the most commonly presenting eating disorders were anorexia nervosa (lifetime prevalence of 6.2%), followed by Other and Unspecified Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders (OSFED, 4.5%; UFED, 4.5%).

- Eating disorders and substance use disorders have the highest all-cause mortality of any major mental disorders.

- People with eating disorders are 3.5 times more likely to die than age-matched peers; one of the causes is suicide.

Over the COVID-19 pandemic, youth mental health was severely compromised. Increased prevalence of mental health problems among adolescents aged 12 to 17 was over-represented by eating disorders (50%) compared to depression (36%) and anxiety (31%).

It is predicted that sustained effects of the pandemic will continue to be experienced by youth. An urgent investment in early intervention for eating disorders in youth is required.

Early intervention for people presenting for treatment

Early intervention in eating disorders to date has been represented by the First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders or FREED. This is a model for emerging adults (aged 18 to 25) with an untreated eating disorder duration of less than three years. Rapid access to evidence-based treatment emphasises active engagement, nutritional improvement, and psychoeducation about the effects of eating disorders on brain development.

Attention is given to family involvement, social media use, and identity formation. This model has been disseminated in tertiary healthcare settings around the United Kingdom. Compared to a retrospective cohort, FREED patients with anorexia nervosa are three times more likely to reach a healthy weight within 12-months, and significantly fewer require intensive treatment. A derivative of FREED, based in low socio-economic primary mental healthcare settings (headspace in South Australia), has also shown robust improvements for participants and cost savings compared to treatment in tertiary settings.

What about people who don’t present to treatment services?

This early intervention approach misses many youth experiencing significant impairment:

- The three in four individuals with eating disorders who do not seek help.

- Adolescents.

-

Youths experiencing early signs and symptoms of an eating disorder who are not eligible for tertiary services.

What is required is an approach to early intervention that can be widely implemented. It should be able to both head young people away from developing an eating disorder and reduce the symptoms of an eating disorder. This need resonates with the 2024 The Lancet Psychiatry Commission call for a transformation in mental health implementation research, which seeks to understand what, why, and how interventions work (or do not work) in real-world settings and identify approaches to overcome barriers to scaling.

An implementation approach to early intervention for youth with disordered eating and eating disorders

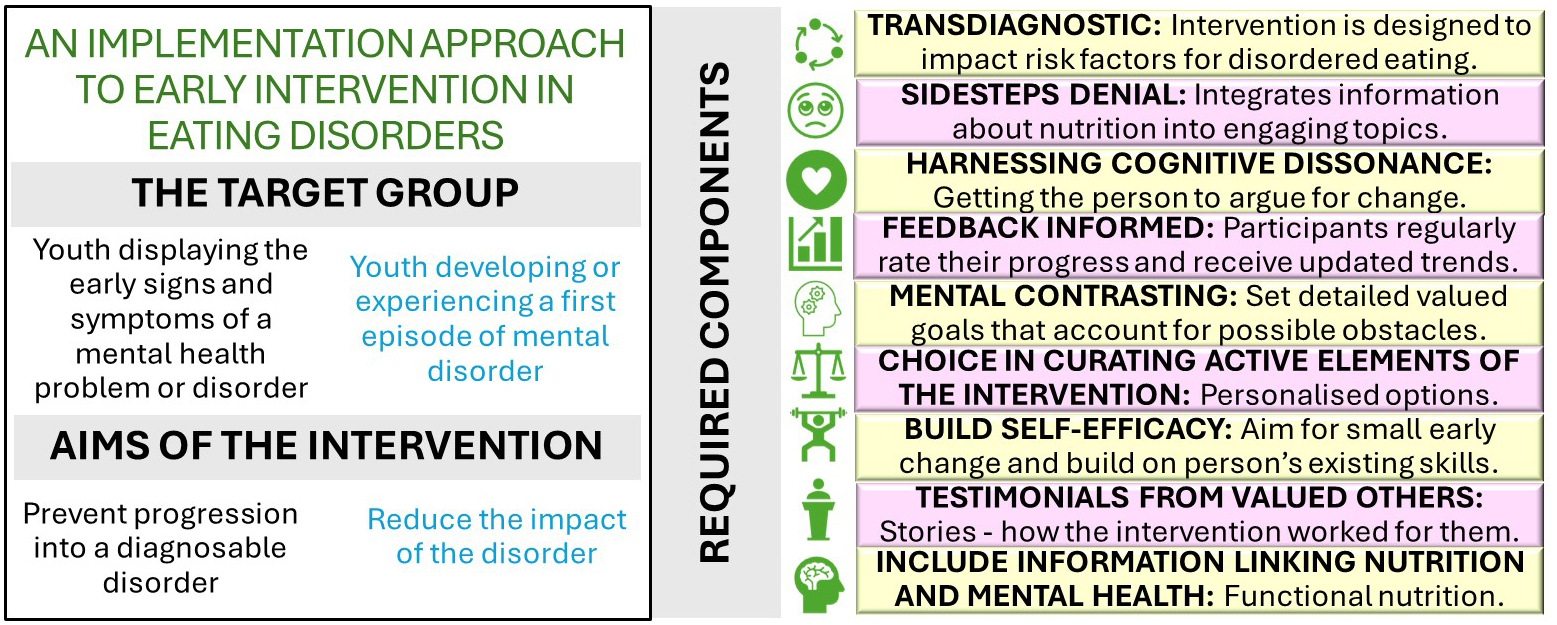

The National Health and Medical Research Council has funded a five-year research program of early intervention in eating disorders (Investigator Grant 2025665). The foundation of this approach is development and testing of brief app- and web-based interventions co-designed with youth to ensure maximum engagement. These interventions will be made freely available. Development will integrate nine evidence-based components (see Figure 1) which have been shown to boost engagement and effectiveness of mental health interventions.

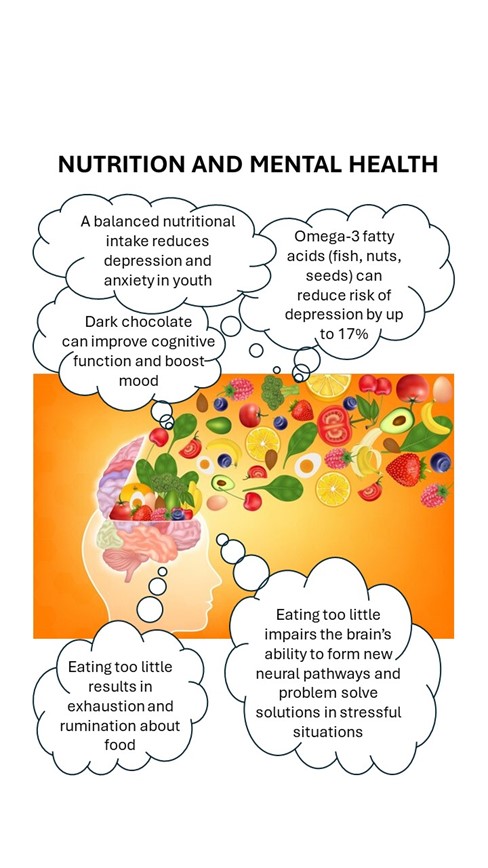

These interventions will be designed to target transdiagnostic processes, defined as mechanisms that are present across disorders and are either a risk or a maintaining factor. This approach is preferable given diagnostic instability and comorbidity, and evidence indicating that mental health problems are best conceptualised along a series of continua rather than as discrete categories. An advantage of using this approach is that it can sidestep the denial that is typical in eating disorders and engage youth in helpful interventions. What is often missing in such approaches, however, is psychoeducation about the beneficial impact of good nutrition on youth mental health (See Figure 2).

For too long, eating disorders have not been seen as a “core mental health business” but rather outsourced to specialist care. This special early intervention in eating disorders focus in Open Access Government reflects the imperative to intervene early in a way that can reach large numbers of young people effectively across the various stages of eating disorder development.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.