In a study published in the European Heart Journal, researchers reveal that babies conceived through assisted reproductive technology, such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF), face a significantly higher risk of being born with congenital heart defects

The study, led by Professor Ulla-Britt Wennerholm from the University of Gothenburg, highlights a trend affecting many children born over two decades across several Nordic countries.

Congenital heart defects

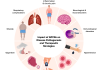

Congenital heart defects, which can lead to life-threatening complications, are already known to be the most common form of birth defects worldwide.

This new research emphasises the impact of assisted reproduction techniques on this issue. The findings indicate that babies born following assisted reproduction have a 36% higher risk of major heart defects compared to those conceived naturally. The risk was found to be 1.84% for assisted reproduction babies, compared to 1.15% for naturally conceived babies.

The study used data from over 7.7 million liveborn children in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, spanning births from 1984 to 2015. Researchers compared outcomes between children born through assisted reproduction methods like IVF and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) with those conceived naturally. Factors such as maternal age, smoking during pregnancy, and the presence of diabetes or heart defects were carefully considered to isolate the impact of assisted reproduction on heart health.

The increased risk was particularly visible in cases of multiple births, which are more common with assisted reproduction. Twins or higher-order multiples born through these methods faced even greater odds of congenital heart defects compared to singletons.

The link between assisted reproduction and congenital heart defects

“We already know that babies born after assisted reproductive technology have a higher risk of birth defects in general however, we have found a higher risk also in congenital heart defects, the most common major birth defect,” commented Professor Wennerholm.

The research also found that the type of assisted reproduction, whether using fresh or frozen embryos, did not significantly alter the risk, indicating a broader influence at play.

Dr. Nathalie Auger from the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre, in an accompanying editorial, emphasised that while assisted reproductive technologies have helped many couples achieve parenthood, they are not without risks. She noted that patients undergoing these treatments often differ from the general population, potentially contributing to both fertility challenges and heightened risks for birth defects.

This research is significant for clinical practice. Early detection and specialised care will be crucial for babies at higher risk of congenital heart defects. As assisted reproduction becomes more prevalent globally, understanding and addressing these risks will be vital in ensuring the health and well-being of newborns.

“In one of the largest studies to date, the researchers found that assisted reproductive technology was associated with the risk of major heart defects diagnosed prenatally or up to one year of age,” Professor Wennerholm concluded.