Tracey Wade, Matthew Flinders Distinguished Professor, provides an insightful examination of the significance of brief early interventions in the treatment of eating disorders

Longer interventions are not always better for mental health

Over the last ten years, it has become apparent that brief face-to-face interventions can be effective for some people with common mental health problems. Two distinctive groups of people receiving therapy can be identified: those who experience “rapid response” and those who experience “gradual response”. Rapid responders show signs of improvement by the fourth session of therapy. (1) Clinically significant change can be achieved over two sessions by 41% of these people. (2) There is a trend for diminishing gains the longer treatment proceeds, with gradual responders not showing benefit after session 26. (1)

This same phenomenon is observed in online treatments for depression and anxiety. Within four sessions, one-third of adults can experience a greater than 50% improvement in symptoms. (3)

Can single-session interventions be effective?

More recently, research has investigated the effectiveness of online single session interventions (SSIs), defined as ‘specific, structured programs that intentionally involve just one visit or encounter with a clinic, provider, or program’. Adults with elevated depression and anxiety were given one online module explaining behavioural activation principles with activity suggestions, a weekly planner, and daily text message reminders across four weeks. (4)

Behavioural activation is an effective intervention for depression that helps people to deliberately practise valued activities by themselves and with others to activate an improved mood. Treatment completion was high (92%), 66% of participants were satisfied with the treatment, and significant moderate reductions in depression and anxiety were maintained at the three-month follow-up. In another study, a comparison of an online five-session intervention and SSI for adults showed both significantly decreased depression and anxiety with similar effects. (5)

Jessica Schleider’s team (6) has been investigating a range of SSIs as a tool for early intervention in adolescents, showing that they can reduce and prevent youth psychopathology of multiple types over three to 12-month follow-up.

Relevance to eating disorders

Examination of brief interventions in eating disorders has been far less common, with concerns that these complex mental health disorders may require longer treatments. (1) This is despite clear evidence that early response is the most consistent and robust predictor of good outcomes across different eating disorders, age groups, and treatment settings. (7) We also know that ten-session cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for non-underweight clients produces improvements of the same magnitude as 20-session CBT. (8)

In 2023, a challenge was issued to the eating disorder field, saying: “The eating disorder field needs to embrace these innovations including developing a “single-session mindset” with greater attention paid to testing the relevance of SSI for eating disorders.” (9)

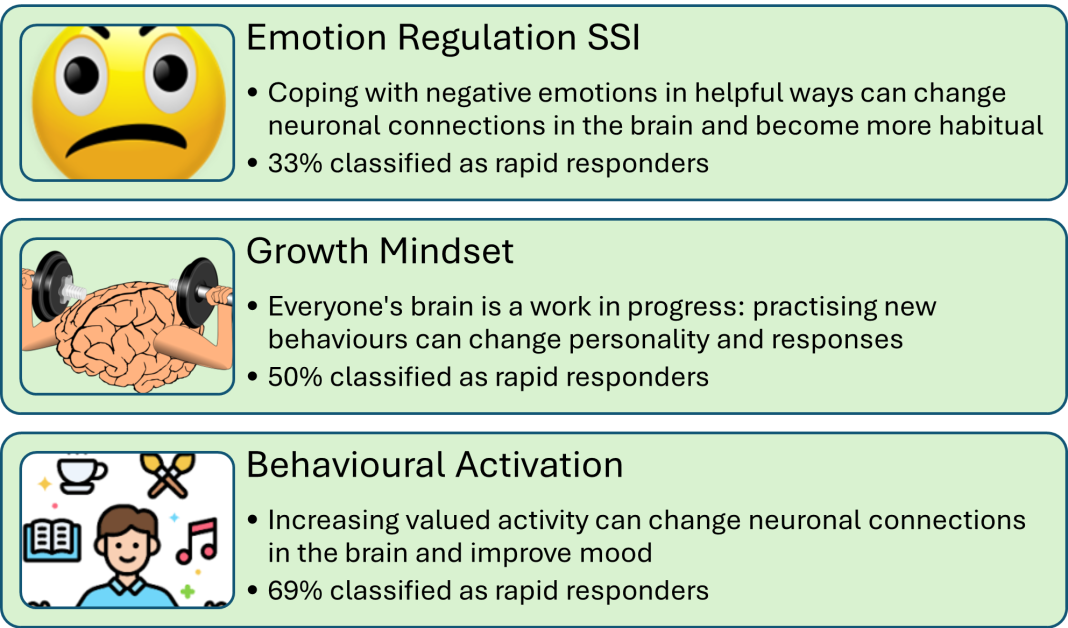

Our current research using SSIs with people with eating disorders (who are not underweight) shows that the use of these while people are waiting for treatment increases by three-fold the likelihood that they will complete subsequent treatment. (10) Further, in the two weeks between assessment and the start of treatment, our research shows that SSIs can identify rapid responders before treatment even begins. As shown in Figure 1, when randomised to receive one of three SSIs, 50% of people reduced dietary restriction by 30% or more before treatment commenced. This early change places them in a better position to do well in subsequent therapy.

What about SSIs in early intervention for eating disorders?

Digital mental health SSIs make sense for adolescents and emerging adults who are starting to experience the symptoms of an eating disorder. This is a group unlikely to come in for treatment, who prefer digital to face-to-face interventions, and many may be rapid responders at this early stage of the development of disordered eating.

Online SSIs have been evaluated in groups of emerging adults aged 18 to 25 years with disordered eating and who are at risk of developing an eating disorder. (12,13) The use of imagery rescripting for early unpleasant memories related to appearance has been shown to produce moderate effect size improvements in disordered eating, body image acceptance, and self-compassion over one-week follow-up. Additionally, psychoeducation on SSI related to the growth mindset and the link with nutrition produced significant reductions in disordered eating and improvements in body image.

Schleider and colleagues (11) have shown small but significant decreases in dietary restriction over three months using a growth mindset SSI or a behavioural activation SSI in depressed adolescents.

The future of digital SSIs in early intervention for eating disorders

Our research team, funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (2025665), is developing and evaluating a suite of app-based SSIs for youth at risk

of developing an eating disorder.

The targets of these apps have been chosen after consultation with people with lived experience of an eating disorder, significant others, clinicians and researchers. The interventions will be codesigned with youth, and evaluated across disordered eating, depression, anxiety and suicidality. If shown to decrease risk and prevent the development of eating disorders, widespread dissemination of these SSIs has the potential to reverse the increased prevalence of eating disorders observed in youth over the last ten years.

References

- Robinson L, Delgadillo J, Kellett S. (2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1566676

- Owen JJ, Adelson J, Budge S, et al. (2016). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.966346

- Bisby MA, Scott AJ, Fisher A., et al. (2023). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000761

- Bisby MA, Barrett V, Staples LG, et al. (2024). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2024.102882

- Bisby MA, Balakumar T, Scott AJ, et al. (2024). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172300260X

- Schleider JL, Dobias ML, Sung JY, et al. (2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.180/15374416.2019.1683852

- Vall E, Wade TD. (2015). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22411

- Keegan E, Waller G, Wade TD. (2022). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2022.2075257

- Wade, TD. (2023). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23930

- Keegan E, Waller G, Tchanturia K, et al. (2024). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2024.2351867

- Schleider JL, Mullarkey MC, Fox KR et al. (2022). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01235-0

- Pennesi J-L, Wade TD. (2018). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1022/eat.22849

- Zhou Y, Pennesi J-L, Wade TD. (2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23370