Kati Rantala, Research Director at the Faculty of Social Sciences, analyses Regulatory Impact Assessment as a policymaking tool

Regulatory policy decisions intend to impact societies in far-reaching ways, affecting people and businesses, organisations and institutions, as well as animals and the environment. However, in an inherently complex world, unknown variables can influence the outcomes of regulations. This is why they do not always work as intended and can also produce harmful unintentional effects.

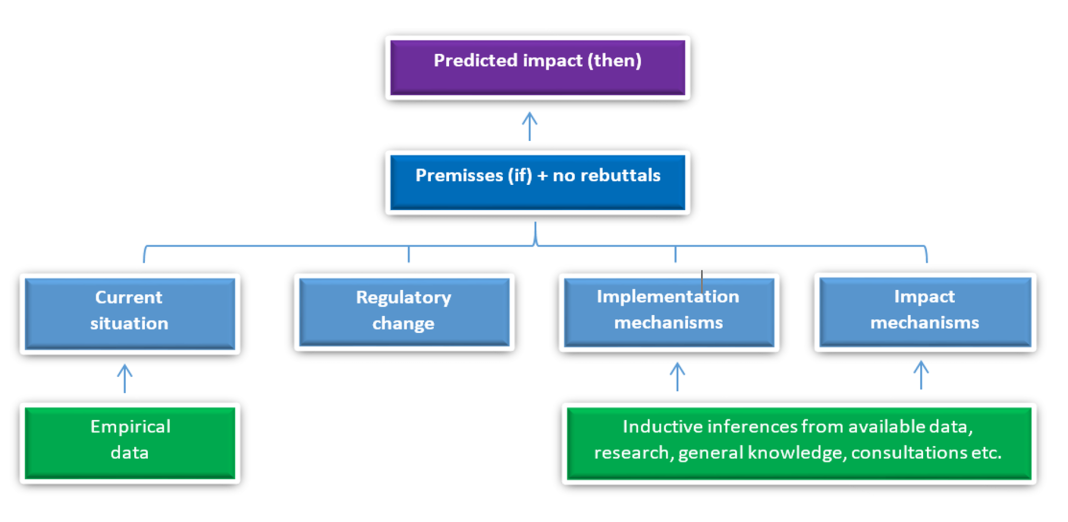

Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) is a tool to assess the likely outcomes of proposed regulations to ensure that choices are well justified. RIA is, therefore, about predicting the future, which is a difficult endeavour. To enhance the use of RIA and its practical utility, my colleagues and I have developed a model of RIA by examining its underlying logic. (1) It offers a realistic and robust framework to address the challenges of RIA.

At the heart of RIA lies evidential reasoning. While there cannot be evidence about the future, one can use evidence or available data to create scenarios about the impacts of regulations. RIAs can employ various sources of data, such as stakeholder consultations, statistics, previous research, and regulatory experiments, as well as methods of analysis, such as quantitative modeling, cost-benefit analysis, and scenario assessments, to name a few.

While it is not possible to predict the future with certainty, evidential reasoning allows us to make informed inferences based on the best available evidence, thereby enhancing responsible decision-making.

The challenge of uncertainty

As a whole, impact assessment is always inductive. This means that being grounded in empirical data, it can only deliver approximations, at best, of the unknown future. Applying Stephen Toulmin’s model of argumentation can significantly help in discerning what type of evidence backs the assessment, what possible counterarguments exist, whether the results are likely or just possible, and under which circumstances. (2)

Yet the overall argumentation of impact assessment can include deductive elements relying on logical relations, such as mathematical calculations or conceptual deduction. If the premises are true in deduction, the outcome is also true. Thus, when deduction is used in RIA, it is crucial to understand the validity of the premises.

As a heuristic tool for locating uncertainties, it is possible to reformulate inductive elements of RIA as deductively valid arguments. To put it simply, one can say that a) the regulation will protect workers unless companies break the law, or b) if companies comply with the regulation, it will protect the workers from inappropriate payment practices. In the former expression, a rebuttal in inductive assessment (unless…) becomes a premise in the latter, deductive argument (if…).

This switch now gives us a premise, the validity of which depends on inductive reasoning about the probabilities and contexts of companies not complying with the regulation. This could also lead to taking action to address non-compliance. The point is that this kind of switch helps us see what we need to know about the world (as premises) to make a credible argument about the future.

Accordingly, we need to understand the circumstances and structural limitations surrounding a proposed regulation in terms of its implementation and impact mechanisms to make meaningful inferences across different countries, areas, cultures, people, and businesses – depending on the case. This includes assessing whether the subjects of a regulation understand it, are capable of complying with its requirements, and are motivated to do so. (3) A large body of research acknowledges that difficulties in these aspects may result in dysfunctional regulation. (4)

Opening up the complexities inherent in RIAs may not directly help in deciding between regulatory options but perhaps that should not even be the point. Although it is challenging to account for all circumstances contributing to regulatory impacts against the real-life situations that regulations affect as interventions, by addressing uncertainties of different types, policymakers can improve the credibility and transparency of RIAs.

The prospects of policy research

One challenge in RIA lies in balancing knowledge production, with all its uncertainties, with political interests. It may occur that premises imply political commitments connected to desired viewpoints, which do not necessarily allow for a balanced consideration of impacts on different types of stakeholders. A commitment to evidential reasoning, as described above and supported by targeted research funding, could be beneficial.

Research is often used to assist in RIA, but perhaps the commissioning of such research could boldly require analysts to delve into the validity of the premises used and the logic and nature of the impact mechanisms presented. Openly acknowledging risks and potential dysfunctions could lead to heightened responsibility in decision-making and ultimately to more effective and well-grounded policy outcomes.

In support of regulatory policy design, it is crucial to understand that different types of regulations – whether controlling, guiding, nudging, or enabling, etc.– have distinct impact mechanisms to begin with. In addition to conducting ex-post evaluations of individual regulations, research could compare the impact mechanisms possibly identified in these evaluations. Identifying patterns of impact based on specific regulatory types would benefit those designing RIAs.

In addition, policy research guiding RIAs should take seriously the principle of inclusive stakeholder participation in knowledge production by acknowledging all affected groups. Many scholars have paid considerable attention to power dynamics and have discovered that those actively participating in regulatory policymaking tend to have the necessary resources, social status, and analytical skills.

However, ensuring balanced consideration of impacts on marginalised, inherently silent stakeholders in practice is often overlooked in policy and research. This is regrettable because regulations often affect these groups in powerful ways through controlling or paternalistic measures. Their practical knowledge of their own circumstances can provide valuable insight into impact mechanisms concerning them.

This would aid in modifying proposals to fit community needs and avoid unintended consequences as a way towards responsible and socially sustainable regulations.

References

- Rantala, K., Alasuutari, N., & Kuorikoski, J. (2024). The logic of regulatory impact assessment: From evidence to evidential reasoning. Regulation & Governance, 18(2), 534-550.

- Toulmin, S. (1964) The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press.

- Vedung, E. (1997) Public policy and programme evaluation. Transaction Publishers.

- For example Griffiths, J. (2003) The Social Working of Legal Rules. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 35 (48): 1–84.