When scientists study biodiversity in a country, state, province, city, or any region of interest, the first thing they typically do is count the number of species in that area. The number of species is one of many methods used to quantify biodiversity. Additionally, it is common for scientists to count the number of organisms, or individuals, for each species.

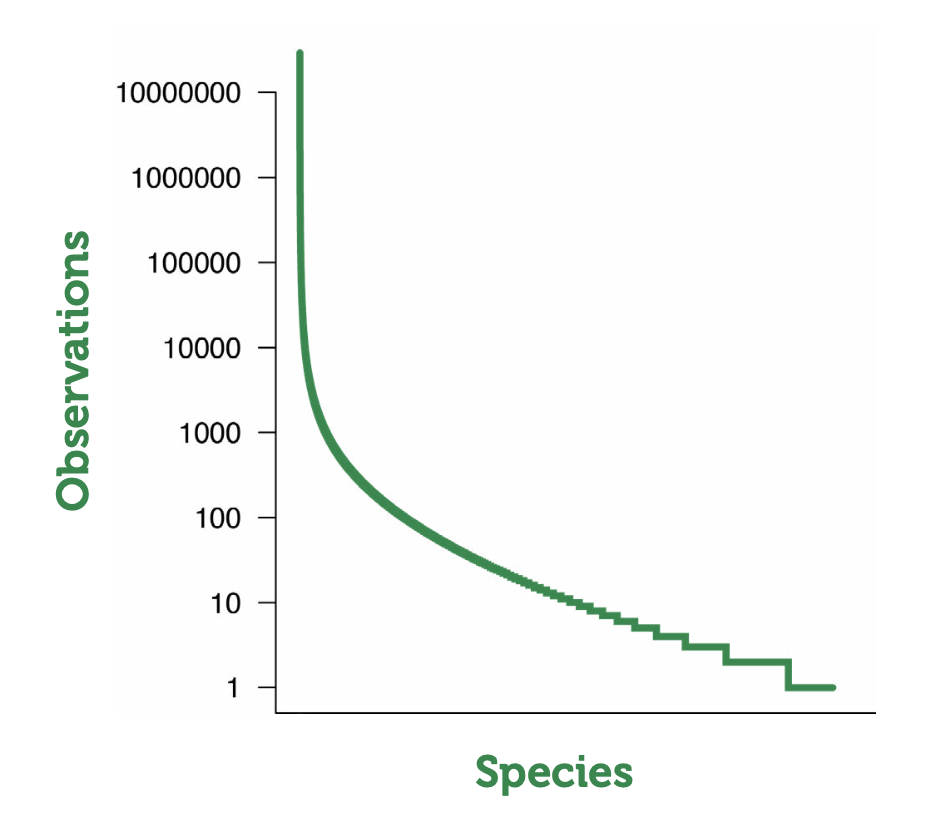

What they systematically find is that there are generally many more species with only a few individuals, while only a few species are common. This has led to the saying, “In biodiversity, there is commonness in rarity.”

How common are rare species?

To illustrate how common it is to discover rare species while studying biodiversity, we can reference data available through the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). This international network, funded by multiple world governments, is dedicated to providing free and open access to biodiversity data from anywhere on Earth. Currently, GBIF has compiled over three billion observations worldwide across all ecosystems, from the ocean depths to the heights of the Himalayas, encompassing all types of organisms, including mammals, insects, algae, and even bacteria.

The data collected by GBIF is impressive and it contains information on a huge number species, though not all species, known to science. A brief survey indicates that data is available on nearly five million species in GBIF. If we organize the GBIF biodiversity data to connect the three billion observations with the five million species, we can truly see how common rarity is (Figure 1).

In conservation biology, important resources are dedicated to protecting endangered species, which are, by definition, rare. As such, it is crucial to understand why a species is rare. This becomes even more important when considering the politics behind biodiversity protection. Typically, a species is protected using political boundaries as a reference. However, although political boundaries are significant for humans, they are irrelevant for other organisms. Consequently, a species might be rare in one country because that country is on the edge of the species’ distribution, while the species may be quite common in a neighboring country. A good example of a species that follows this pattern is the Siberian flying squirrel, which is considered at risk of becoming endangered in Finland and the Baltic countries but is known to be quite common in Russia.

Some general guidelines for conservation planning

It thus becomes important to have guidelines to understand why a species is rare. By knowing why a species is rare, we can make smarter decisions about how to allocate the limited resources available to protect and conserve biodiversity in the best and most efficient way possible. One approach to making these decisions is to study the species we want to protect from three related viewpoints: (1) the overall area where a species is found, (2) the different locations where the species lives within that overall area, and (3) the number of individuals (the abundance) that can be counted at the locations where the species resides. By examining individual species with these guidelines, we can gain a better understanding of why a species is rare and make better decisions about the actions to take for its protection.

To illustrate how this approach can be applied, let’s consider the wolverine, a species deemed vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Currently, the wolverine is primarily located in the northern countries of the world, including Canada, the USA (particularly Alaska), Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Therefore, the area it inhabits is vast, covering millions of square kilometers.

Similarly, the area covered by an individual wolverine, its home range, is typically very large. For example, in Canada, the wolverine occupies less than 0.5% of the total area where the species could be found. One reason wolverines maintain such extensive territories is that they are scavengers and primarily feed on the carcasses of dead animals. Additionally, it is highly unusual to find many individuals in one location at the same time, resulting in low abundance across the entire area they inhabit.

Because the wolverine requires such a large territory in areas with low human density, it could benefit from the establishment of large protected areas in northern regions to better conserve this species. Interestingly, some of the world’s largest protected areas are located in these northern regions (a map of the current protected areas can be found at this website), which serves as an advantage for the wolverine. However, having protected areas within the general territory of the wolverine is only part of the solution, as protecting areas in locations with already minimal disturbances may not suffice for the wolverine’s survival. Considering what we know about this species, it may be worthwhile to propose various policies and actions aimed at reducing hunting and poaching. In the end, what matters is finding methods closely tailored to the species’ specific needs to enhance its survival and reproduction.

A key to success is to understand how species reproduce and survive

In ecology, there are modeling methods specifically designed to investigate the impact of various events on the reproduction and/or survival of individuals, depending on their life stage (infants, young adults, or older individuals). These modeling methods are typically referred to as “population models.” The idea behind population models is that if we can understand how a change affects the survival or reproduction of individuals at a specific life stage of a species, we may be able to address the various threats that impact survival or reproduction for that particular life stage.

To illustrate the benefits of using models like population models to propose and implement better and more efficient conservation strategies, let’s examine two very different endangered species: the Mojave Desert tortoise and the Copper Redhorse.

The Mojave Desert tortoise

The Mojave Desert tortoise is a critically endangered species residing in the Mojave Desert in the southern United States, east of Los Angeles and south of Las Vegas. Over the past few decades, this species has been steadily declining, with fewer than 20 known populations, most of which are considered to have a worryingly low number of adults capable of reproduction.

When examining how this species has changed over time, it is legitimate to wonder why the Mojave Desert tortoise is in such bad shape. Although we can point to many factors like forest fires, climate change, predators feeding on the tortoise, or urbanization as potential pressure points impacting the population of this species, using population models, ecologists and conservation biologists have taken a slightly different perspective. Namely, they have proposed asking the question: “Is the Mojave Desert tortoise endangered because it has trouble reproducing or is it because it dies prematurely? Since this species has been under threat for many years, it has also been studied with the goal of better understanding how it reproduces and survives.

Using population models, in the mid-1990s, ecologists were able to assess that the decline of the Mojave Desert tortoise was due to urbanization encroaching on habitat essential for the survival of this species. They also determined that the presence of predators, such as crows that eat the newborns, had little impact on the decline of the species. They reached this conclusion because they realized that Mojave Desert tortoises are more sensitive to events affecting the survival of reproducing adults. Findings like this one are valuable when the goal is to protect and conserve a species like the Mojave Desert tortoise because they provide important, precise guidelines on various actions to take to safeguard this endangered species. Specifically, to benefit the Mojave Desert tortoise, conservation efforts should focus on reducing fragmentation and urbanization in areas where the species is found, such as by decreasing the number of roads in these regions.

Of course, little can be done against events like the massive forest fires that recently burned vast areas around Los Angeles, where the Mojave Desert tortoise is found. However, the destruction caused by the forest fire may present an opportunity to rethink how to plan and rebuild the affected area with a broader perspective, for example, by accounting for species like the tortoise to prevent it from going extinct.

The Copper Redhorse

The Copper Redhorse is a fish species found only in Québec, Canada, and is known to reproduce exclusively in the Richelieu River; however, adults can also be found in the St. Lawrence River near Montréal. Currently, only two reproduction sites are known to exist, and the population has been declining for many years. In an effort to help save the Copper Redhorse population, significant measures have been in place for several decades to stock the Richelieu River with Copper Redhorse by artificially adding larvae and fry where the species is known to reproduce. Unfortunately, this initiative has had little success in increasing the population size.

In contrast to the Mojave Desert Tortoise, our understanding of how the Copper Redhorse reproduces and survives in its natural environment is far from complete. Nonetheless, a recent study allowed us to determine that events affecting younger individuals are likely to influence the Copper Redhorse population. Therefore, the idea of adding new individuals to the population through stocking was indeed a sound strategy. But why has the Copper Redhorse population not increased since we have been stocking it for over 20 years? It has been suggested that the number of individuals added during stocking was insufficient.

However, it was also shown that to increase the size of the Copper Redhorse population, hundreds of thousands to millions of fry and larvae would need to be added to the Richelieu River, a number far exceeding the capacity to produce these individuals. Since population models suggest that the best chance of helping the Copper Redhorse recover is by increasing the survival of younger individuals, we need to find clever ways to achieve this goal. One proposed idea was to stock slightly older individuals. These individuals are more resilient, and the population model indicates that far fewer individuals would be needed to recover the species; a number that is manageable to produce in practice.

The primary challenge in protecting and saving the Copper Redhorse is that the actions taken cannot solely focus on the species while disregarding everything else. We must consider the other living organisms found in the Richelieu and St. Lawrence rivers, where the Copper Redhorse resides, as well as how these rivers are used for recreational, social, or commercial activities. Therefore, it would be politically challenging to establish a protected area in the waters around Montréal, which is one of the major trade routes in North America. Consequently, conservation biologists need to find innovative ways to prevent species from becoming extinct that take into account not only the biology and ecology of the species they wish to protect but also the society that inhabits this area.

Conclusion

Conservation approaches are challenging mainly because the goal of conservation biologists is to protect biodiversity while maintaining a good relationship with the people living in these areas. Therefore, it involves practices that focus not only on the species that need protection but also on the communities that interact with those species. Only when biodiversity and society respect each other and can benefit from one another can we truly find effective solutions.

Additional reading

If there is an interest in learning more about why species are rare, a recent scientific article entitled “How and why species are rare: towards an understanding of the ecological causes of rarity” would be a good read (it can be found here).

To learn more about the Mojave Desert tortoise. Two scientific articles expand the brief presentation I made of this species, the first one is entitled “Modeling Population Viability for the Desert Tortoise in the Western Mojave Desert” and the other is entitled “Move it or lose it: Predicted effects of culverts and population density on Mojave desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) connectivity”.