In this first of a four-part series, Kati Rantala from the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Helsinki examines silent stakeholders in regulatory policy – identifying who they are, explaining their significance, and exploring ways to enhance their involvement

The article begins a series of four pieces focusing on silent stakeholders in regulatory policy: who they are, why their position matters, and what can be done to improve it. Generally, silent stakeholders are individuals and groups who remain outside the participatory processes involved in creating regulations that impact them. Insofar as silent stakeholders are affected by regulations, they are relevant stakeholders despite their social status.

Reflecting on the ideal of participatory governance and the normative foundations of regulatory policy – such as human rights conventions and Better Regulation guidelines from organizations like the OECD and the European Commission – those affected by regulations should have the opportunity to voice their concerns on the matters at hand. However, despite the overall emphasis on inclusive participation in policy documents and notions of tailored consultation approaches in regulatory toolkits, participation in regulatory matters tends to involve mostly public officials and strong interest groups, while individuals rarely participate. (1) One might assume that civil society organizations fill the gap by speaking on behalf of silent stakeholders, but many of these organizations claim to represent them without proper authorization. (2)

The contents of this article broadly apply to public policymaking, but they are particularly significant in the context of national lawmaking. Legislation can have profound implications for the lives of silent stakeholders, whether with supportive or controlling intentions. Regulations that impact many disadvantaged individuals are often found in areas such as health and social care, childcare, policies concerning older adults, persons with disabilities, immigration, and criminal justice, to name just a few.

The issue extends beyond the ideal of participation. Consultation procedures are also essential for gathering relevant knowledge to prepare regulations, including conducting regulatory impact assessments. If the knowledge base is skewed or insufficient, policy decisions risk not working as intended, which is particularly unfortunate if the aims are meant to benefit silent stakeholders. Moreover, policies may end up working in the wrong direction, producing unintentional harmful effects. The term ‘silent stakeholders’ thus underscores the exclusion from participatory processes despite having significant stakes involved.

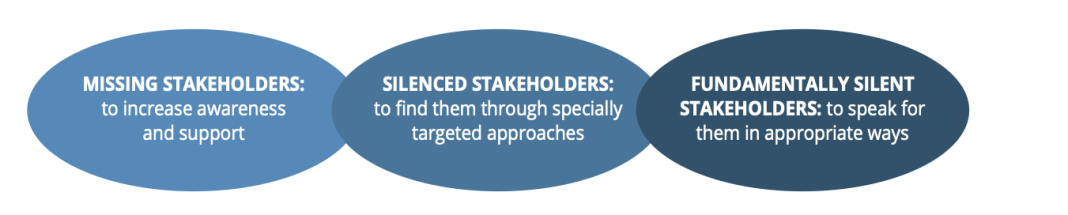

We can identify three types of silent stakeholders. Most of the public appears to fall into the category of ‘missing stakeholders,’ referring to individuals who may lack knowledge about which policy processes to comment on, even if they are interested, and who are unaware of opportunities for participation. (3) These individuals often have limited literacy regarding participation procedures and policy documents, which can lead to information overload and hinder their engagement. In many cases, increasing awareness of participation opportunities combined with appropriate support could be beneficial.

Silent stakeholders in the second group have the capability to express their concerns, but they may not be recognized as legitimate stakeholders by policymakers due to paternalistic or controlling intentions. This lack of recognition may be compounded by stereotypical perceptions of these individuals as irresponsible, threatening, irrational, or possessing some other type of personal deficiency. For these groups, targeted methods can help lower the barriers to participation. In Finland, the SILE project (4) has engaged in consultation procedures with prisoners and former asylum seekers alongside lawmakers from the relevant ministries. These consultations have yielded valuable insights that would not have been possible to attain otherwise. (5,6)

Thirdly, the concept of ‘silent stakeholders’ acknowledges a broader range of socio-cultural, biological, and psychological obstacles to engagement. These obstacles can include challenging daily conditions, illness, cognitive disabilities, extreme marginalization, and past trauma or stigma, which may lead to internalized barriers to participation stemming from feelings of inadequacy or unworthiness. Consequently, some silent stakeholders may remain fundamentally silent despite outreach efforts.

Nevertheless, all silent stakeholders possess crucial insights derived from their lived experiences, which are invaluable when formulating policies that impact them. This includes their understanding of personal circumstances, such as potential socio-cultural obstacles, driving factors, abilities, immediate environments, social norms within their communities, and the bureaucratic systems they navigate – all of which shape how regulations influence their lives. Nonetheless, they often lack the ability to overcome structural obstacles, such as traditional participatory frameworks, to effect change. As a result, due to their marginalized position, silent stakeholders are vulnerable to epistemic injustice. It involves the exclusion, systematic distortion, or misrepresentation of relevant knowledge in policy-making processes by undermining or disregarding potential contributors. (5)

Of course, in the case of fundamentally silent stakeholders, direct consultation is not possible. However, one can consult those who live or work with these individuals in their everyday lives, such as close family members, implementers of regulations, service providers, and grassroots-level civil society organizations. Too often, these actors are also among the silent stakeholders themselves.

In the upcoming articles, we will delve deeper into the structural forces that contribute to the position and silence of silent stakeholders and explore whether their overall situation could be improved. Individual success stories, such as those involving prisoners, are a good start. However, achieving significant change ultimately depends on the will of those in charge.

References

- Alasuutari, N. & Rantala, K. (2025) Stakeholder engagement in regulatory policymaking in a neo-corporatist setting: Assessing diversity and balance in open consultations. Interest Group and Advocacy.

- Urbinati, N. & Warren, M. E. (2008) The concept of representation in contemporary democratic theory. Annual Review of Political Science 11: 387–412.

- Farina, C. R. & Newhart, M. J. (2013) Rulemaking 2.0: Understanding and getting better public participation. Cornell e-Rulemaking Initiatives Publications 15.

- The SILE project is funded by the Strategic Research Council (SRC), which is an indepedent body established within the Research Council of Finland.

- https://www.hiljaisettoimijat.fi/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/CONSULTATION-OF-PRISONERS-ON-THE-REFORM-OF-THE-IMPROSONMENT-ACT.pdf;

- https://www.hiljaisettoimijat.fi/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ASYLUM-SEEKERS-AS-INFORMATION-PROVIDERS-IN-LAW-DRAFTING.pdf

- Fricker, M. (2007) Epistemic injustice. Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press.