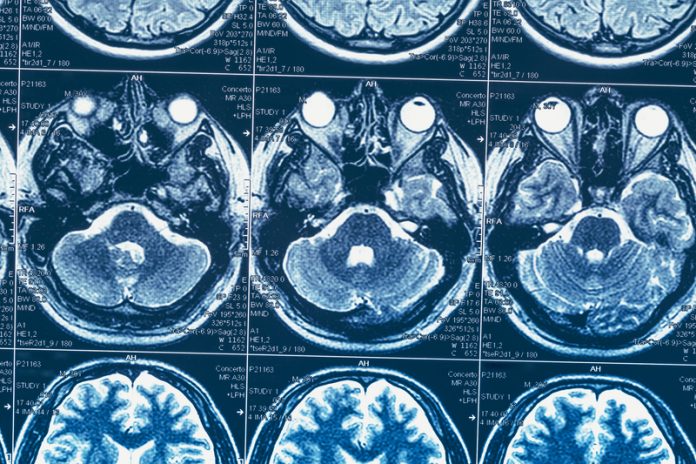

Research into curious bright spots in the eyes on stroke patients’ brain images could one day alter the way they are assessed and treated

A team of scientists at the National Institutes of Health found that a chemical routinely given to stroke patients undergoing brain scans can leak into their eyes, highlighting those areas and potentially providing insight into their strokes.

The researchers performed MRI scan on 167 stroke patients upon admission to the hospital without administering the chemical, gadolinium. They then compared them to scans taken using gadolinium two hours and 24 hours later.

Roughly three-quarters of the patients experienced gadolinium leakage into their eyes on one of the scans, with 66 percent showing it on the two-hour scan and 75 percent on the 24-hour scan. The phenomenon was present in both untreated patients and patients who received a treatment, called tPA, to dissolve the blood clot responsible for their strokes.

In healthy individuals, gadolinium remains in the bloodstream and is filtered out by the kidneys. However, when someone has experienced damage to the blood-brain barrier, which controls whether substances in the blood can enter the brain, gadolinium leaks into the brain, creating bright spots that mark the location of brain damage.

Richard Leigh, M.D., an assistant clinical investigator at the NIH’s National Institue of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the paper’s senior author said: “It looks like the stroke is influencing the eye, and so the eye is reflective of what is going on in the brain.

“Clearly these results are preliminary, so future studies will have to be attuned to this to fully understand its impact.”

MRI replacement

Gadolinium was typically present in the front part of the eye, called the aqueous chamber, after two hours, and in a region towards the back, called the vitreous chamber, after 24 hours. Patients showing gadolinium in the vitreous chamber at the later timepoint tended to be of older age, have a history of hypertension, and have more bright spots on their brain scans, called white matter hyperintensities, that are associated with brain aging and decreased cognitive function.

In a minority of patients, the two-hour scan showed gadolinium in both eye chambers. The strokes in those patients tended to affect a larger portion of the brain and cause even more damage to the blood-brain barrier than the strokes of patients with a slower pattern of gadolinium leakage or no leakage at all.

The findings raise the possibility that, in the future, clinicians could administer a substance to patients that would collect in the eye just like gadolinium and quickly yield important information about their strokes without the need for an MRI.

“It is much easier for us to look inside somebody’s eye than to look into somebody’s brain,” Dr. Leigh said. “So if the eye truly is a window to the brain, we can use one to learn about the other.”