In the first of a series of five articles exploring the phenomenon of multilingual EU law, Dr Karen McAuliffe, PI on the European Research Council funded project ‘Law and Language at the European Court of Justice’, explains the importance of taking language into account when thinking about law

Law permeates almost every part of our lives. ‘The law’ governs what we can and can’t do in a society, regulating our rights and duties at local, regional, national and international levels. Often, non-lawyers (and indeed some lawyers) view the law as a definitive set of rules, perhaps somewhat complicated to navigate without specialist advice, but clear and precise, nonetheless.

However, examining the process and production of law through the lens of language allows us to understand ‘the law’ in a very different way. Language and law are inextricably linked – the law is an inherently linguistic construct: it is largely created, interpreted and applied through language. Language is, therefore, an extremely important part of, and has a significant impact on the development of any legal order.

While this link between law and language exists across all legal orders, at every level, it is more visible and arguably more important where the law in question is multilingual. In today’s globalised world, multilingual law permeates many aspects of our daily lives and is more important than ever before. The intense process of globalisation in the latter half of the 20th century has led to a rapid increase in the production of international treaties and agreements, the creation of international courts as well as a reliance on international arbitration.

Much of this globalised legal work is performed through translation and much of the underpinning law on which such work is based exists in a multi- or pluri-lingual sphere. Nowhere is this phenomenon of multilingual law more evident than in the context of the European Union, which produces law in 24 languages, with the aim of it being applied uniformly throughout (at the time of going to press) 28 member states.

The EU’s multilingual law consists of treaties, as well as secondary legislation (regulations, directives, decisions etc.), all of which are considered equally authentic in each of the 24 EU official languages in which they are produced. The multilingual nature of that legislation is generally evident to those coming into contact with such documents on a regular basis.

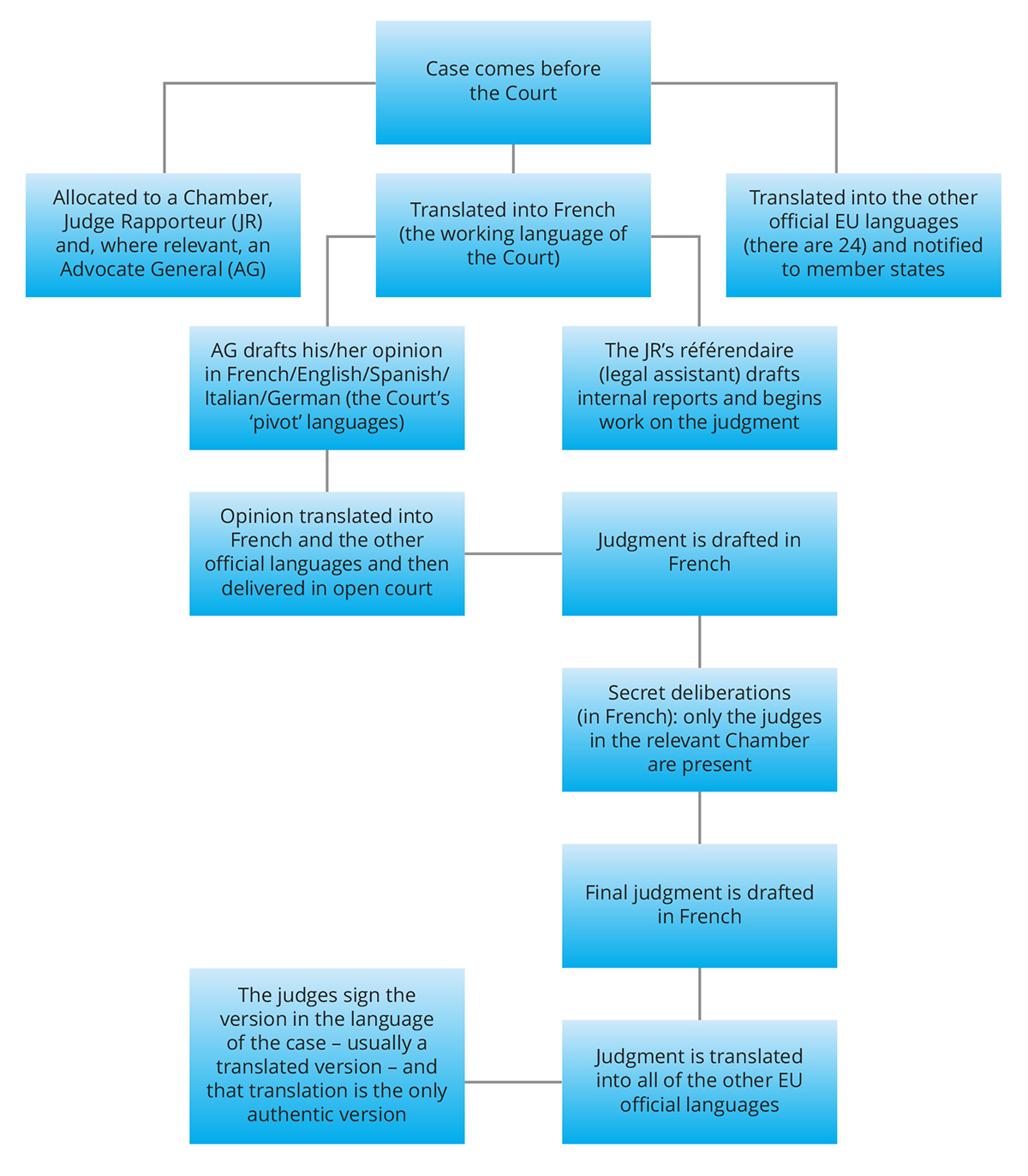

However, there is another source of EU law, the multilingual nature of which is not always so obvious: decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). When a member state or other legal party to an action before the CJEU engages with that court, it does so in its choice of one of the 24 EU official languages. Since all correspondence in relation to the relevant action, including notification of the ‘authentic version’ of the judgment, is carried out in that one language, the multilingual nature of the process behind the scenes is not always apparent. However, given the importance of CJEU case law as a source of EU law, its multilingual nature should not be ignored.

Although the CJEU produces case law in up to 24 language versions, it has a single working language: French. On the surface, that court is, in effect, a monolingual institution: working internally in French and producing translated case law in up to 23 languages. However, within that surface-level ‘monolingualism’ are layers of hidden translation. CJEU judgments are drafted by multiple authors in a language that is generally not their mother tongue. They then go through many permutations of translation into and out of up to 23 other languages. The final version of a judgment is a collegiate document and the authentic version of that judgment will usually be a translation. Exploring that multilingual production process and what it might mean for our understanding of EU law is the focus of an EU Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) project entitled ‘Law and Language at the European Court of Justice’ (LLECJ), based at the University of Birmingham, UK.

Based on the theoretical assumption that a linguistically ‘hybrid’ community, such as that of the CJEU, functions primarily through language interplays, negotiations and exchanges; and that the ‘process’ within any institution will necessarily affect its ‘output’, the LLECJ project investigates the cultural and linguistic compromises at play in the creation of the CJEU’s multilingual case law. The project aims to shed greater light on the development of EU case law and consequently on EU law more generally, by taking account of the multilingual nature of that law.

By clarifying the ways in which language plays a key role in determining judicial outcomes, we can challenge EU scholarship to look beyond more conventional approaches to the development of a rule of law which draw on law alone, and develop a fuller and more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon of multilingual EU law. The LLECJ project is comprised of three separate but interlinked subprojects investigating: the limitations of producing a multilingual jurisprudence; the linguistic construction of de facto ‘precedents’ in CJEU case law; and the linguistic aspects of the role of Advocates General at the CJEU. More information about the project, including publications and reports, is available on the LLECJ website: www.llecj.karenmcauliffe.com

This article is the first in a five-part series focusing on the LLECJ project and examining the phenomenon and impact of multilingual EU law. Forthcoming articles will examine certain research questions posed and results obtained in specific subprojects and will explore what such results may mean for our understanding of EU case law and EU law more generally.

Please note: this is a commercial profile

Dr Karen McAuliffe

Reader in Law and Birmingham Fellow

Law School, University of Birmingham

Tel: +44 (0)121 414 7269