Nishat spoke to Ed O’Donovan, Head of Protection at Front Line Defenders, to dissect pandemic obstacles faced by human rights defenders – especially Indigenous communities in Brazil

Human rights defenders (HRD) work on the margins of society, to protect vulnerable groups and create political change. Often, this involves working against a Government that is indifferent or downright hostile. On the other hand, protective laws can already exist- yet the implementation of the law is as vividly unreal as a fever dream. This kind of work is difficult, mentally draining and isolating. It is also what the late politician John Lewis would describe as “necessary trouble.”

Ed O’Donovan works for an organisation that protects HRDs in trouble. As of 28 September, their website flags that 457 activists are currently at risk. The threat comes from their own Governments, but also from the wider community they are working to change. Front Line Defenders was founded in Dublin, in 2001.They work with non-violent HRDs to protect the rights that are written in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted in December 1948 by the UN General Assembly. The organisation won the 2007 King Baudouin International Development Prize for “their efforts to combat the isolation faced” by HRDs, and in 2018 the UN Prize in the field of Human Rights, awarded once every five years to winners like Martin Luther King and Malala Yusafzai.

In light of COVID-19, many Governments have made sweeping legal reforms and mostly redistributed resources to the containment of the virus. Visibility is one of the key weapons that HRDs have against the entities that want to stop their work. With the public understandably fixated on an omnipresent pandemic, we have collectively looked away from policy implications that aren’t immediate.

How are organisations like Front Line Defenders functioning in the semi-darkness of a global pandemic?

The flaws of online human rights work

Firstly, how is the mental health of the HRDs you’re working with? How are they ensuring their physical safety without access to in-person networks of support?

“I think that is definitely one of the biggest issues that we have heard. Numerous HRDs are in contact with us and they have found this quite anxiety-inducing, both in terms of the isolation and the fact that they’re not able to continue their work. Their work is what they’re passionate about and currently they’re not able to continue supporting and defending the rights of others. It’s the first time that a lot of people will be working from home, and perhaps using the internet so much to do this work.

“At the beginning of the lockdown in early March, we would provide for our HRDs, security – both physical, and emotional security about working from home, to see that could kind of help them as they adjust and to give them some directions about the type of tools they should be using, what security issues they should be aware of. A couple of weeks ago, we released a guide [here it is] as everyone has turned to Zoom to try and continue conversations with colleagues that were based in the field.

“HRDs who turn to insecure tools in order to continue their work, unfortunately in some cases are especially at risk because the authorities often know about technical vulnerabilities and will try to target HRDs.

“Your second point about danger facing people now that others can’t critically attend to them, unfortunately that is a big issue and at the moment it is difficult to address that. We feel that Indigenous communities are now much more isolated. Despite situations of lockdown or curfew, land development activities have continued to take place in the community and left those people much more vulnerable than before, because they don’t have access to the help.

“This also brings the additional risk of outsiders coming in and possibly carrying the virus with them, to Indigenous groups who unfortunately are more vulnerable to diseases than others. This carries a double risk to the community. I think something extremely worrying is that we have been trying to assist with the digital side of things as much as possible to ensure that people can be safer online.”

Are you thinking of a specific Indigenous community?

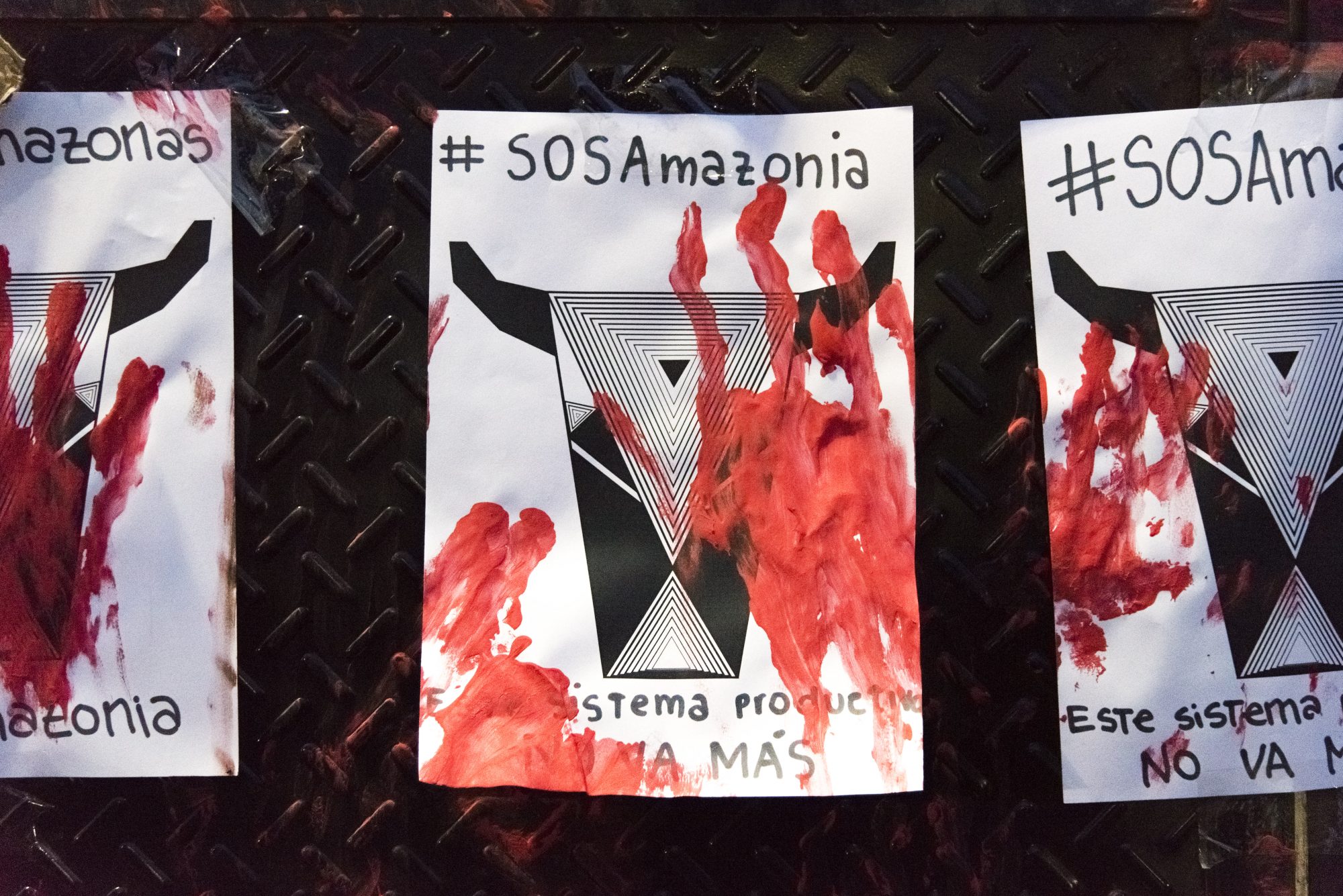

“Brazil for instance, is a country where we have a lot of contact with Indigenous groups there and we’ve worked with them on security for a long time. The situation there, as terrible as it already is in Brazil, because there has been a 25% increase in deforestation [according to the INPE data released in June], in the first few months of 2020 compared to the same time last year.

“This just shows how advantage has been taken of this situation, to carry out all of these activities that aren’t as possible when networks of support and protection are fully operational – which they can’t be during these times.”

New virus, same treatment

You work with human rights defenders, often they’re stateless, they don’t have recourse to public funds like the rest of us. When there is a vaccine, what can organisations do to make sure they reach HRDs?

“Within the context of COVID, it’s a huge challenge to enable them to continue their work in the first place, so while we wouldn’t necessarily be within our mandate to get vaccines to the community.

“We would treat our role as enabling those, making sure they’re able to work securely. Because in many countries, those who are trying to spread the word about vaccines, making sure those who are vulnerable can get it – they’ll be subjected to attacks, smear campaigns and then the other violations that we’ve seen right throughout the course of this pandemic. Those who have been trying to raise awareness and have been handing out PPE are constantly being attacked.

“So we do very much a continuation of the work we do along those lines, ensuring that those who most need the space, to educate, to raise awareness and to provide that protection.”

On lingering legal limitations

Whilst some reforms are temporary, others have no sunset clause – as we’ve seen in the Philippines legislation set to continue until 2022. Are you worried about any policies specifically?

“The latest figure I’ve seen is 300 measures affecting 126 countries, affecting freedom have been introduced. Unfortunately, many don’t have expiration clauses, but some do. We’ve seen as you’ve said, in the Philippines, attempt to introduce legislation which just isn’t likely to be lifted.

“Similarly, in Niger, a bill that allowed the Government access to digital communications, which has a big knock-on impact. At the International Centre for Not-For-Profit Law they have established a really good tracker, where they go country by country, looking at the restrictions which have been introduced, which impact specific freedoms.

“It’s a good view of how broad this kind of executive overreach has become over the past three months.”

BLM as a HRD movement

We’ve seen that Governments are hesitant to label their own activists as HRDs, even if they applaud the same actions elsewhere. Do you think the HRD framework could support the Black Lives Matter movement within the US?

“Part of that is a broader question about how the US interacts with the human rights framework, internationally. And the reality is that, it doesn’t really.

“We’ve done a little bit of work over the past number of years, trying to reach out to the current administration where they are more at risk than they have been in the past. In answer to your question, taking the dynamic in the US at the moment and the polarisation, I don’t think it would make that much of a difference. I think it may make a difference more at the global level, where protests have been taking place and leaders of BLM have been attacked.

“You’re completely right, Governments are often very wary of referring to their own activists as HRDs. But I do think a HRD framework has evolved over the last few years and been recognised in more and more countries. At a mainstream level, there are really good organisations and allies in the US working on these issues. I think it hasn’t punctured the political bubble yet.

“From country to country there is definitely a possibility to use the HRD framework and I think that is going to become a much more common currency. Especially when the pandemic lifts, and there’s where I place my hope.”

On the role of the UK in Hong Kong

I’m going to come back to the UK, in relation to the Hong Kong protesters arrested a couple of months ago. What kind of foreign policy decision would you make in this situation?

“It’s difficult given China’s position now in the world, and that the UK is much weaker in the international stage because of Brexit. We have the inevitability of having to curry close favour with some countries to make trade deals.

“I can recognise that we’re coming from a very difficult starting point. Nevertheless, the UK has released updated guidelines on HRD earlier this year, which highlighted the importance of HRDs and that they make up a focus area for UK foreign policy.

“First of all, I do think being extremely vocal about it, about the ongoing arrests, the crackdown, about this new security law that’s been introduced – which eventually makes Hong Kong another part of China. Mainstreaming that vocalness across Government departments is important. Not just focusing on the Human Rights Ambassador, but also when those trade deals are taking place, and then delegations are going to China. Human rights should always be on the agenda. It shouldn’t be cornered off into one part of diplomacy but mainstreamed across the entire spectrum of UK diplomacy.

“I saw the proposals on offering Hong Kong residents who have had British passports a longer visa or route to citizenship in the future. One thing is also creating a specific stream for human rights defenders in Hong Kong who need to claim asylum – dedicated to journalists, and human rights defenders. In this situation, a substream specifically for Hong Kongers, given the history, to allow rapid processing into the UK would be a huge benefit. This is not to say that we want people to leave Hong Kong, we don’t – but there are times where leaving is unavoidable unless you want to be serving 10 years in prison as a result of the new Security law.

“Considering the history and the failure of the British administration since 1997 to hold China to account, there should be at least some kind of gesture to those who are still upholding traditional British values in Hong Kong today.”

Thanks for taking the time to talk to me. Is there anything specific you want us to remember?

“One last thing which I think is of note is the risk that Indigenous communities and other land rights protectors face.

“There is a danger that when societies come out of lockdown, that there will be continued increases in illegal mining and lobbying and deforestation, used as an excuse to kick-start economies. And there’s a real danger that some of the environmental protection legislation which has been introduced in various countries over the past number of years will be ignored or temporarily suspended – on the excuse of uplifting the economy.

“And that will have a knock-on impact of creating more conflict and putting more people working in these areas, putting whole communities at risk. And unfortunately, it seems to be already happening in Brazil.”