Andrew Brodbelt, Consultant Neurosurgeon at The Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust, describes what we need to know about brain tumour diagnosis & therapy

‘You’ve got a brain tumour’ is probably one of the scariest things one can hear. A diagnosis could lead to a life-changing disability or even death. There is also the possibility that the tumour or its treatment will change who you are and what makes you, you. Over the last 50 years, there has been no revolutionary change in the management of people with brain tumours, but there has been a slow, steady improvement in all aspects of treatment and care, and there is hope for the future.

After a new brain tumour diagnosis, the first person who really understands the condition and can offer treatment is often the oncology neurosurgeon. This gives us an opportunity, and a responsibility, to provide enough information for people to start understanding what this means for them, their family, what their options are and maybe in the future.

Treating brain tumours

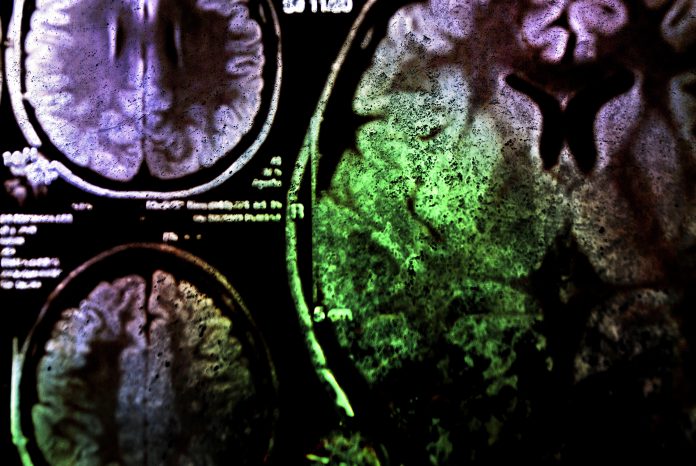

Operating on a person with a brain tumour can be challenging. New techniques are regularly developed to help take as much of the tumour out as possible, whilst the chance of causing life-changing damage always remains a factor. It has often been predicted that neurosurgery for brain tumours will become unnecessary, but in reality, techniques continue to progress exponentially. The popularity of computer gaming has led to developments in 3D and virtual reality, which has improved brain tumour operative planning software. This information can be integrated into the operative guidance and visualization systems and holds hope of further progress. However, advancing in neurosurgery often comes with significant costs, and ongoing investment in new technology is essential.

Radiotherapy uses ionizing radiation to kill cancer cells and may be used after surgery. Stereotactic radiosurgery (a single very focused dose) and conformal radiotherapy (multiple contoured doses) are now standard and commonplace. Proton beam (multiple focused doses) access is expanding, but more excitingly, boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) may further improve outcomes whilst minimising the cognitive side effects of more extensive radiation treatments. BNCT is in the early stages of development but allows for the targeting of treatment of all the cancer cells at a cellular level, whilst minimising adjacent radiation exposure. This could help transform the way we approach cancer treatment in the near future.

Brain tumour research

Enormous effort has gone into research that targets the tumour cells through chemotherapy or immunotherapy, and there has been some progress. One of the challenges is that brain tumours may have different cell molecular mutations (in their DNA or cell receptors, for example) in different parts of the tumour. Some cells can adapt to treatment, leading to more resistant areas growing during or after therapy. Clinical trials (usually a study comparing a new treatment to the standard treatment) provide hope and guidance for the future but can take a long time and are expensive. ‘Adaptive clinical trials’ offer an alternative, as the standard treatment can change during the trial or other new treatments can be offered and integrated, but the challenge is making them statistically significant and meaningful. A small trial of cannabis compounds, the results only recently published in February 2021, has led many people to take cannabis oil, which may not be the same compound as that used in the trial. A new trial, ARISTOCRAT, of cannabis for people with brain tumours is due to start recruiting in 2022.

Tumour treating fields

A more unusual brain tumour treatment is tumour treating fields. Electrodes fixed to the scalp and attached to a portable battery deliver an electric current to the tumour for at least 18 hours a day. Randomised controlled trials have shown significant benefits when added to conventional therapy. Patients tolerate this treatment well, although they do get some skin irritation. At €20,000 per patient per month, they are prohibitively expensive for the NHS. Discussions are urgently needed between the company, Public Health England, and NICE to look at ways of making this more affordable and available for NHS patients.

A cure for brain tumours?

COVID-19 has affected so many aspects of our lives, and the same is true of people with brain tumours. During the early days of the pandemic, there was an increased risk of complications and death in people who had treatment for their brain tumour if they caught COVID-19. The chemotherapy was stopped or reduced for some patients. Patients were forced to self-isolate for extended periods of time and could not see their families and friends. Hugging became a dangerous activity. Thankfully, as the vaccination programme progresses, the risks are reducing.

Despite progress in treatment and care, having a brain tumour is pretty rubbish. Many people with brain tumours will still die of the disease, and/or be disabled. Understanding this, and being honest, when asked, from the beginning can help people to understand and cope with their diagnosis. Integrating people early into the palliative care network, hospices and extra income support is essential. Rehabilitation and progress in augmented mobility systems and developments originally designed for patients with spinal cord injury offer exciting avenues for further research work.

A cure for brain tumours remains the objective of everyone working and researching in this field. Exciting developments continue in all areas of this work, and although improvements continue, a major breakthrough is long overdue. Neurosurgeons will continue to have a major role in research and these people’s multidisciplinary care.