US pay champions are struggling to find a compelling positive story in the new pay versus performance disclosures; Stephen F. O’Byrne, President of Shareholder Value Advisors Inc., explains

There is a broad consensus among compensation consulting firms and proxy advisors that the conventional approach to US executive pay – providing a high percent of pay at risk withtargetpaysetatthe50th percentile – achieves the three basic objectives of executive pay. The high percent of pay at risk ensures a strong incentive to increase shareholder value, while setting target pay at the 50th percentile retains key talent (because target pay doesn’t drop below the 50th percentile) and limits shareholder cost (because target pay doesn’t rise above the 50th percentile).

A leading compensation consulting firm, Pay Governance, said in 2018 that ‘corporate governance in general and of executive compensation has improved dramatically over the past 20 years.’ (1) The proxy advisor Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), in its 2024 proxy review, noted that failed say-on-pay resolutions had fallen to a record low (<1% for the S&P 500) and added that ‘many compensation committees appear to be doing a better job at addressing investor concerns’ following a low say-on-pay vote. (2)

The conventional wisdom has been strongly embraced even though executive pay disclosures have not shown a high correlation between pay and performance. The correlation was low – according to conventional wisdom – because equity compensation was reported based on the stock price at the date of grant when all the incentive comes from post-grant changes in value. Limited studies, such as a Pay Governance study of 27 S&P 500 companies over the years 2007-2011, found that realizable (or ‘mark to market’) pay had a much higher correlation with TSR than grant date pay (0.70 vs 0.33). (3)

The need to rely on limited studies ended in 2023 when the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission adopted new ‘Pay Versus Performance’ (PvP) disclosure rules requiring companies to report a five-year history of CEO ‘mark to market’ pay and performance. For the first time, pay is reported on a mark-to-market basis, showing the value of current-year grants based on the year-end stock price and the change in value during the year of prior-year grants that were unvested at the start of the year.

Both Pay Governance and ISS have published studies arguing that the new mark-to-market pay demonstrates high levels of pay-performance alignment. Pay Governance calculated pay and performance ranks for 159 S&P 500 companies and found a much higher TSR correlation for mark-to-market pay than for grant date pay, 0.58 vs. 08. (4) ISS measured pay-performance alignment for 938 companies based on how often mark-to-market pay and TSR had the same sign, positive or negative. ISS found an alignment of 83% in 2022. (5)

These two studies don’t provide compelling evidence of pay- performance alignment. Neither adjusts for market pay or peer group performance. The correlation found by Pay Governance, 0.58, implies that performance explains only 33% of the variation in pay. A high frequency of ‘same sign’ alignment, the measure used by ISS, is consistent with a low correlation of the variables. In my analysis of 1,097 PvP disclosures for 2022, I found 68% ‘same sign’ alignment, but the correlation of mark to market pay and TSR was only 0.18.

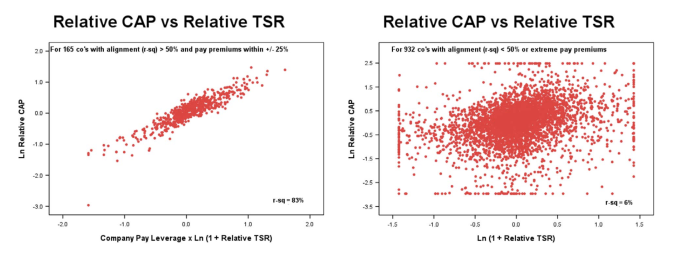

When we adjust for market pay and peer group performance, we get a result that really challenges conventional wisdom. Relative performance, measured by the natural log of (1 + relative TSR), explains only 7% of the variation in relative pay, measured by the natural log of (cumulative mark to market pay/ cumulative market pay). This finding is based on 4,388 observations, using 1, 2, 3, and 4-year cumulative pay and performance for 1,097 CEOs with 4+ years in office.

However, shifting to the values of relative pay and relative performance leads to three big insights. The first is that we can measure key pay dimensions at the individual company level. We get four pay dimensions when we calculate the regression trendline relating log-relative pay to log-relative TSR. The slope of the trendline is pay leverage, a measure of incentive strength; it tells us the percent increase in relative pay associated with a 1% increase in relative shareholder wealth. The correlation gives us a measure of alignment. The intercept is a measure of performance-adjusted cost; it’s the pay premium at peer group average performance. The slope divided by the correlation measures relative pay risk.

The second big insight is that only 165 (15%) of these 1,097 CEOs are good on two counts: relative performance explains 50%+ of the variation in relative performance, and the pay premium at peer group average performance is moderate, within +/-25%. The third big insight is that these 165 companies show high pay-performance alignment, unlike the other 932 companies (see charts above).

The big challenge for US pay champions is to figure out why the conventional wisdom only works for 15% of companies.

References

- Pay Governance, “CEO Pay As Governed by Compensation Committees: The Model Works!”, April 12, 2018, available at paygovernance.com.

- ISS Governance, “Board Elections and Executive Compensation in the 2024 U.S. Proxy Season”, July 31, 2024, available at issgovernance.com.

- Pay Governance, “Executive Pay At A Turning Point: Demonstrating Pay For Performance and Other Best Practices in Corporate Governance”, 2nd edition, November 12, 2012, available at paygovernance.com.

- Pay Governance, “SEC PvP Using CAP: Does CAP Continue To Demonstrate Strong Alignment with TSR in the Second Year of Disclosure”, July 29, 2024, available at paygovernance.com.

- ISS Corporate Solutions, “What the New Disclosures Say About Pay vs. Performance,” available at isscorporatesolutions.com.