Acute care hospitals in Japan need to restructure their management strategies, says Hiroki Konno, Professor of College Economics at Nihon University

In April 2022, the biennial revision of medical fees took place in Japan. The recent revision of medical fees has increased the tendency to allocate resources, with an emphasis on acute care, regional packaged care, and home care. Therefore, acute care hospitals in the region need to restructure their management strategies.

For 17 years, acute care hospitals have been stratified according to hospitalisation fees based on nurse staffing levels. Over time, medical staff in the most heavily staffed acute care hospitals have developed a sense of pride in their status as regional acute care hospitals. However, the medical functions provided by hospitals are no longer viewed as a hierarchy but as a segregation of functions in the region. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) explicitly included a policy of segregation as a fee system for inpatient acute care in the 2018 revision of medical fees. The fee system that desegregates medical functions can be expected to promote efficiency in the provision of medical care and contribute to reducing costs. This study reviewed the fee system for hospitals and described its impact on thyroid cancer treatment.

Current medical fee system for inpatient care

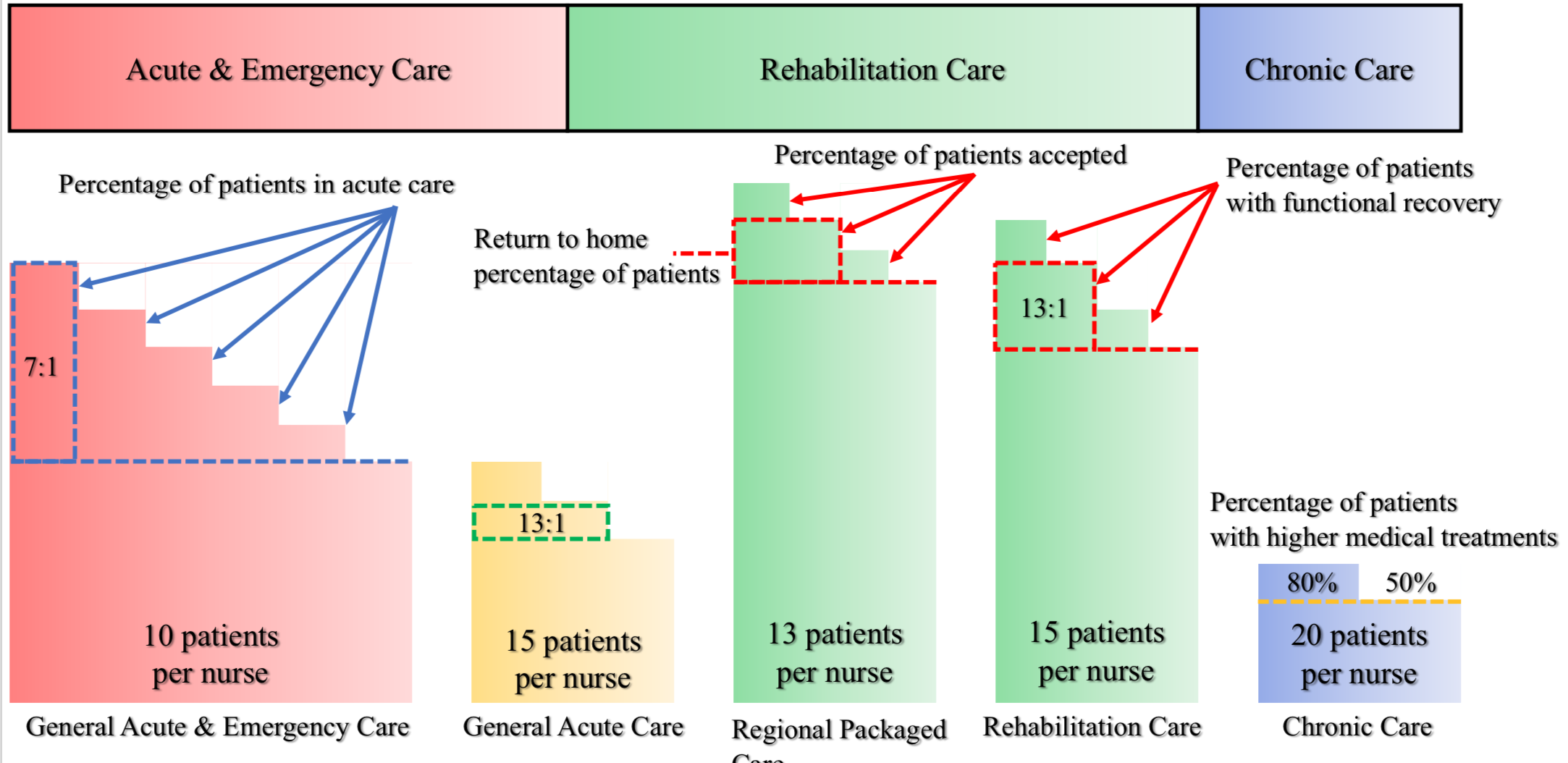

The MHLW has classified the medical fee system for inpatient care into five categories since April 2018; 1. General Acute & Emergency Care, 2. General Acute Care, 3. Regional Packaged Care, 4. Rehabilitation Care, and 5. Chronic Care. The fee system for inpatient care has combined ‘basic fee’ with ‘fee for percentage of patients’. The standard for nurse staffing level in acute care hospitals is based on ten patients per nurse (10:1).(Figure 1)

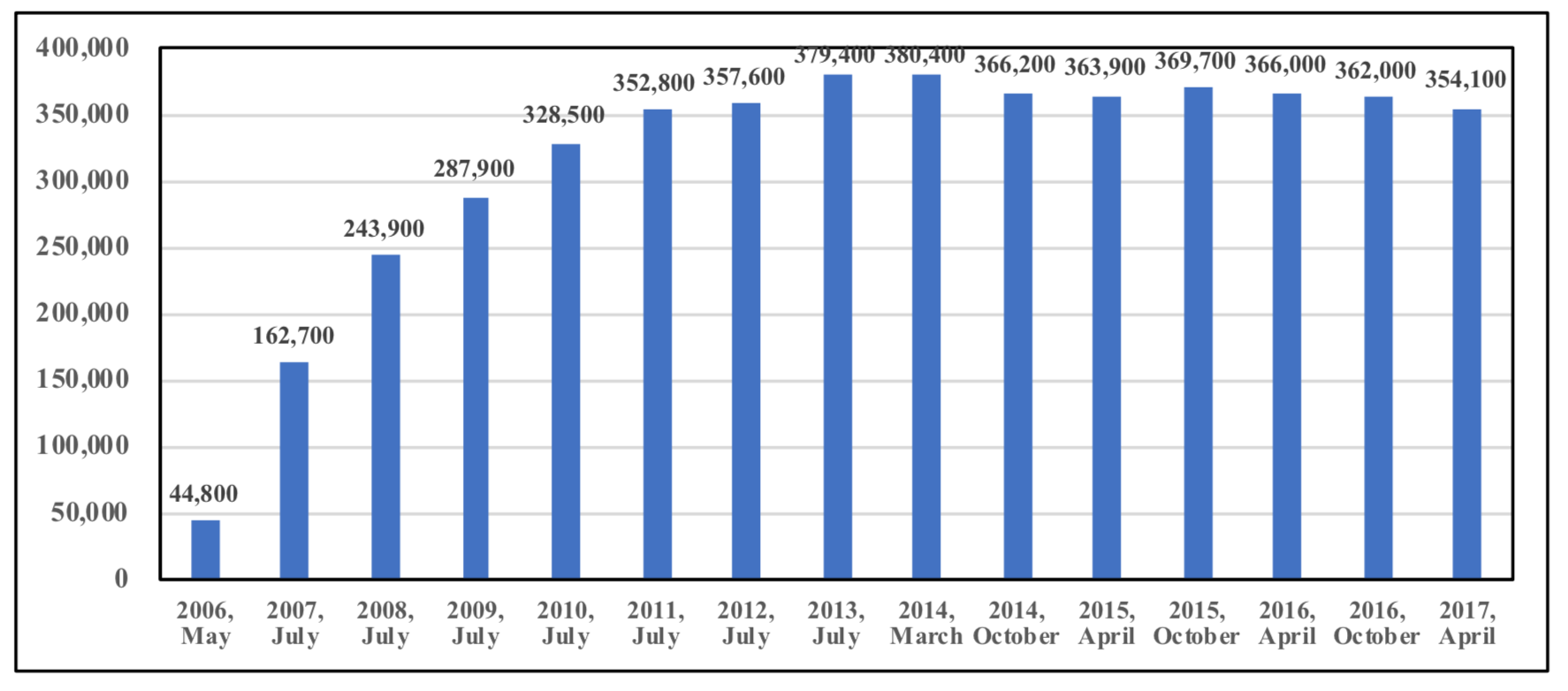

However, the nurse staffing level in acute care hospitals in Japan has generally been seven patients per nurse (7:1). The 7:1 nurse staffing level was established by the MHLW in 2006, while the other levels were categorised as 10:1, 13:1, and 15:1 or higher. Despite the MHLW’s policy objective that emergency hospitals deserved the 7:1 nurse staffing level, many acute care hospitals applied it because the requirements were not strict enough.

The MHLW responded to this situation by progressively tightening the requirements, resulting in an increase in the number of “7:1 hospital” over the nine years to 2014. (Figure 2) Over time, administrators and their staff at hospitals accredited as “7:1 hospital” have become increasingly proud of themselves, leading to delays in the segregation of medical functions in the region.

However, as acute-care hospitals have been able to voluntarily participate in the Diagnosis Procedure Combination/ Per-Diem Payment System (DPC/PDPS) since 2004, they have gradually joined this system and discharged patients earlier. The Length of Stay (LOS) of patients undergoing thyroid tumour resection has also been significantly reduced. The average LOS for patients decreased from 16 days in 2004 to 8 days in 2022. Acute care hospitals were thus forced to desegregate medical functions through stricter requirements for the 7:1 nurse staffing level and the introduction of the DPC/PDPS.

Directions in medical policy implies by the fee system for inpatient care

Three policy directions can be inferred from the fee system; 1. The “basic” nurse staffing level of acute care hospitals should be 10:1, 2. Although the fee levels for wards of regional packaged care and wards of chronic care are relatively high at present, once the number of wards has been filled, their fees will be reduced and will mainly be based on a graduated contingency fee, and 3. Patients admitted to wards of chronic care will be limited to those requiring higher medical treatments, while those requiring lower medical treatments will be transferred to a Nursing Care Medical Clinic.

• First, hospitals that have aimed to be accredited as “7:1 hospitals” will be freed from the effort to meet the requirement. At the same time, this implies that this requirement is likely to be further tightened in the future. Hospitals currently struggling to meet this requirement will soon find it impossible to do so.

• Second, although the current level of fees for wards of regional packaged care and wards of rehabilitation exceeds that of acute care wards, this is largely due to policy inducements. This is because the amount of medical resources required by regional packaged care and rehabilitation care does not inherently exceed that of acute care. It is for this reason, that the fee level will be inevitably lowered once these wards are filled. However, given the current tiered contingency fees, it is expected that in the medium term, the fee level will be reduced and will mainly be based on a graduated contingency fee.

• Third, the fee system for chronic care wards provides additional fees according to the proportion of patients receiving higher medical treatments. This system is related to the planned abolition of long-term care beds and establishing a Nursing Care Medical Clinic. As the medical resources required for patients in chronic care wards are not necessarily likely to be provided in hospitals, it is ideal that patients should be transferred to elderly care institutions or Nursing Care Medical Clinics. Therefore, patients in chronic care wards will be limited to those with higher medical treatments in the medium term, and the number of wards will most likely be reduced.

The fee system for acute care hospitals has been converted to an appropriate one based on reality

The fee system for acute care has shifted from a system based on nurse staffing levels to one based on the proportion of acute patients. Patients with early-stage thyroid cancer undergo thyroid tumour resection in an acute care hospital and are discharged within approximately a week, whereas patients with stage 3–4 thyroid cancer receive chemotherapy in an outpatient setting in an acute care hospital and are then treated at home.

The promotion of segregation of medical functions through inpatient fees is expected to reduce costs by keeping the provision of acute care to the minimum necessary and transferring patients to the next stage of their diseases. Although the reduction in LOS for thyroid cancer treatments is a remarkable achievement, the reform of medical provision in Japan is still in its infancy.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.