Professor Anup Basu from Queensland University of Technology explains the process of delegating financial decision-making to spouses in old age

Ageing can cause cognitive abilities to decline, adversely impacting financial decision-making capacity. Although in many married households, one spouse is primarily responsible for managing household finances, discharging this responsibility can become challenging with age, and it may become necessary to share it with the other spouse.

Recognising when and how to share or delegate financial decisions to the spouse is crucial to prevent the risk of financial mismanagement and hardship in old age. This issue is further complicated as couples age. Despite years of research into factors that determine who takes charge of finances in the household, there needs to be more focus on how this responsibility shifts among older couples.

Financial management and responsibilities in ageing couples

Our recent research, funded by a Linkage grant from the Australian Research Council and Dementia Australia, sheds light on the influences that shape the distribution of financial management and responsibilities in ageing couples. We examined how older married individuals delegate financial decision-making tasks to their spouses. Gender imbalance in financial decision-making within households is a well-known phenomenon, with men traditionally having greater control over household finances.

We were particularly interested in whether such gender differences persist in the delegation of financial decision-making. Additionally, we wanted to learn about other factors that can potentially influence delegation to spouses. For example, if one spouse is more or (less) skilled with money management, do they tend to take on (or give up) more responsibility?

Sixty-four couples aged 60 years or older participated in the study. The couples were all married and living together. They first participated in a delegation experiment in which both spouses took part individually. Each couple was given ten financial decision-making tasks that are commonly encountered in daily life, like managing credit card payments or making investment decisions. They had to choose the best response from four options for each task.

For example, when choosing a deposit account to invest $4,300 for two years, the options included different accounts with varying interest rates and payment frequencies. All participants had the choice to attempt each task themselves or transfer it to their spouse. They earned points for selecting the best response, regardless of who answered, and scoring more points made them eligible for a lucky draw of prizes, which included iPads, Kindles, or Fitbits.

To understand how control over delegation influences an individual’s willingness to delegate, we randomly assigned couples to two groups. Participants in the first group were allowed to transfer to their spouse whichever tasks they wanted to. However, in the second group, once a participant chose to delegate a task, all subsequent tasks were automatically transferred to their spouse.

After completion of the above delegation experiment, participants also took a financial competence test. The tasks included:

- Writing cheques to pay bills.

- Analysing bank statements.

- Making budget-conscious shopping decisions.

Participants also answered questions about their financial awareness and knowledge. The results of this test were used to determine if having higher or lower financial competence than one’s spouse influenced the delegation of financial tasks. Finally, the participants completed a cognitive assessment in which they rated their spouse’s current mental abilities compared to what these were ten years ago.

We observed that initially, participants delegated fewer tasks to their spouses, but as the tasks became progressively more complex, they tended to delegate tasks more often. Still, a majority of participants (70%) chose not to delegate any task to their spouse, indicating a strong inclination to retain control over financial decisions. We found that in the vast majority of couples where delegation took place, only one spouse delegated to the other.

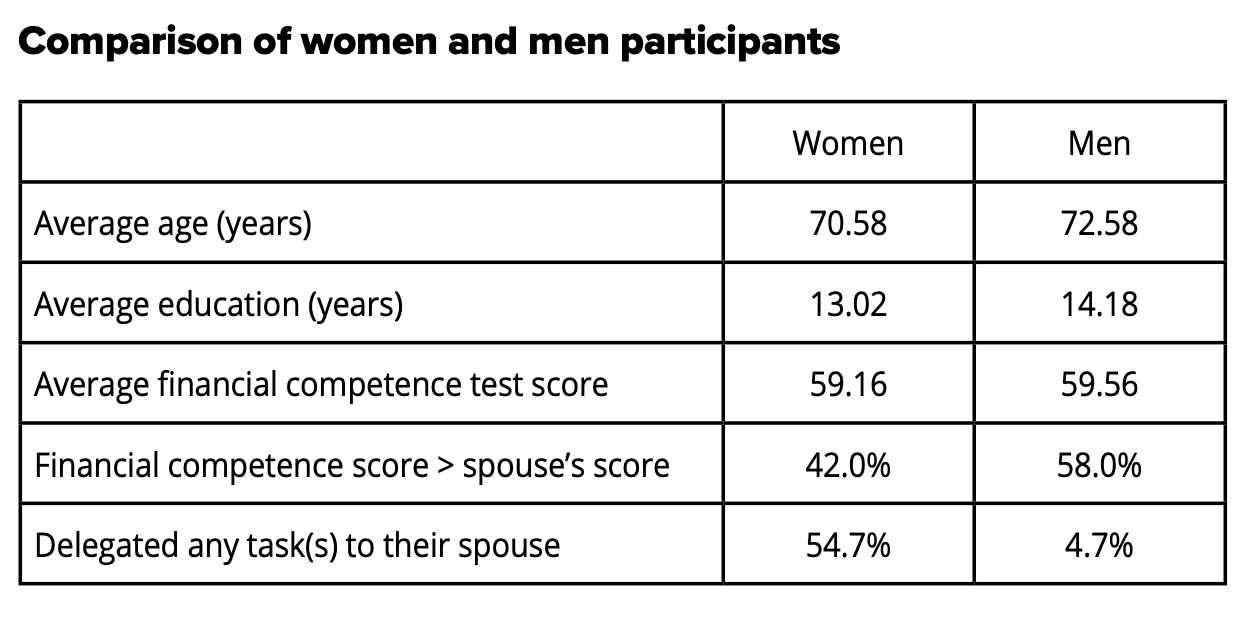

There was a stark difference in delegation based on gender. Approximately 92% of those who delegated tasks to their spouse were women. Less than 5% of men delegated any task compared to nearly 55% of women participants who delegated one or more tasks to their spouses. We found that the difference in financial competence or educational qualifications between the partners did not explain the gender difference in delegation behaviour. In our study, the average financial competence test scores were very similar for both genders. While financial competence relative to one’s partner influenced an individual’s willingness to delegate, its role was secondary compared to gender.

What the research results suggest about financial decision-making

Our results suggest that the most likely reason for the gender imbalance in the delegation of financial decision-making in ageing couples is the sense of identity and social norms – the perceived role of men as primary financial decision-makers within marriage. Delegation requires giving up control, and as financial decision-making has been traditionally viewed as ‘men’s work, delegating these tasks to their spouses leads to a sense of losing control and self-identity among men.

These results raise concerns about women’s financial well-being in old age since they often outlive their husbands and, therefore, disproportionately bear the adverse consequences of poor financial decisions. Suppose financial decisions are not delegated in a timely manner. In that case, women can find themselves unprepared to take over such responsibilities when their partners die or suffer from severe cognitive decline like dementia.

We also found that those with less control over delegation – those who could only make irrevocable decisions – were less likely to delegate tasks. They often wait until tasks become exceedingly difficult before passing them on. In contrast, those individuals who have the choice to revoke delegation or assign tasks to their spouse selectively are more willing to delegate.

These findings have important practical implications for substituted decision-making mechanisms, such as Power of Attorney, among older people. A better understanding of provisions such as the authority to revoke a Power of Attorney or use a ‘springing’ Power of Attorney (which becomes effective only upon the occurrence of specific events) may encourage older people to put such arrangements in place sooner rather than later.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.