Ragui Assaad, Professor from Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota, explores the upcoming resumption of demographic pressures on the Egyptian labour market and what can be done about it

Although unemployment rates have been falling in Egypt in recent years, this trend will likely reverse in the next five to ten years as the “echo” generation comes of age and starts entering the labor market and substantially increasing labor supply.

Exploring the Egyptian labour market

Unemployment in Egypt has always had a substantial structural component linked to demographics, as it is highly concentrated among young, educated new entrants to the labor market. When the growth of the youth population slows, as was the case in the past decade and a half, there is reduced demographic pressure on the labor market and unemployment tends to decline. As the growth of this group resumes from 2025 to 2035, labor supply pressures will increase, and there will be substantial upward pressure on the unemployment rate during this period (Assaad, 2022).

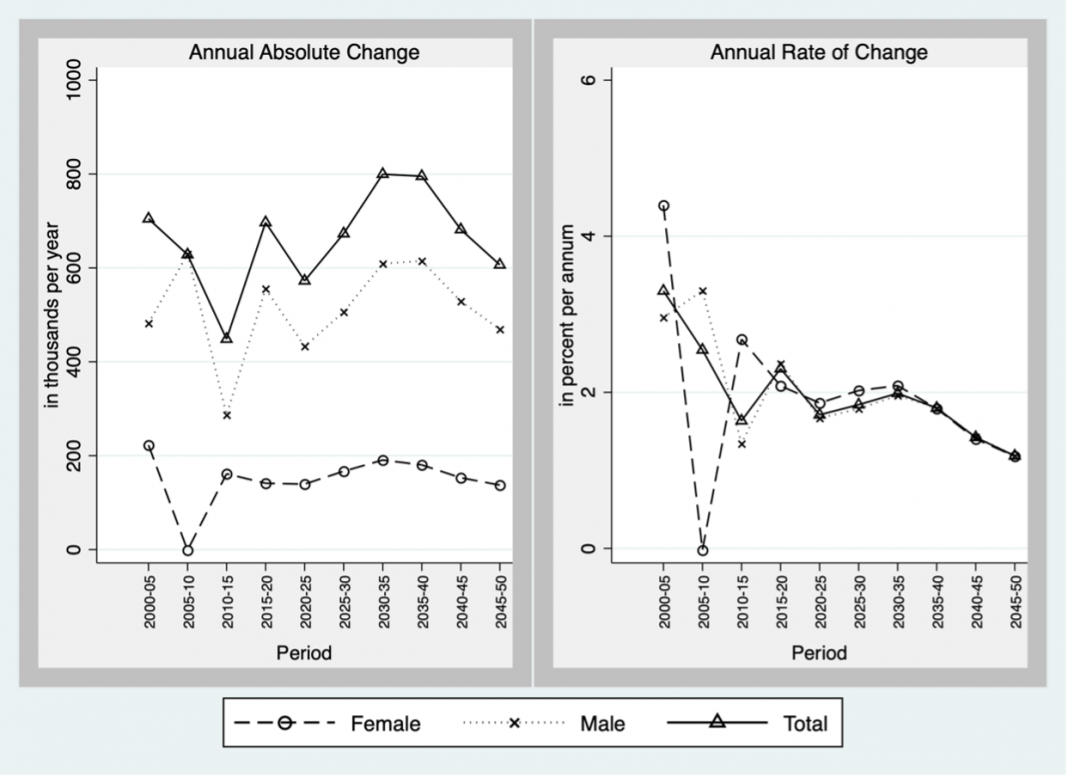

The echo generation comprises the sons and daughters of the “youth bulge” generation, which resulted from rapid declines in infant and child mortality rates in the early to mid- 1980s when fertility rates were still relatively high. The youth bulge generation reached child-bearing age from the mid-2000s to the early 2010s, also coinciding with a period of increased fertility from 2008 to 2014, resulting in a substantial baby boom that lasted roughly from 2005 to 2015. The echo generation, born during this interval, will be of age to start entering the labor market from 2025 to 2035, which will substantially increase the number of new labor market entrants and the rate of growth of the labor force. As shown in Figure 1, the annual increment to the labor force will increase from under 600,000 a year in 2020-25 to 800,000 a year from 2025 to 2035. This will also be a period of rising growth rates after the recent dramatic slowdowns in labor force growth.

These dramatic increases in new labor market entrants will translate into substantial labor supply pressures in the Egyptian labor market. Given the gradual rise in educational attainment in Egypt in recent years, it is projected that more than two-thirds of labor market entrants in 2030 will have achieved at least secondary education. It is well established in Egypt that unemployment rates are usually highest for those with secondary education and above, resulting in further upward pressure on unemployment (Krafft, Assaad, and Keo, 2022).

Women’s participation in the labor market has been falling in recent years in Egypt. In fact, the female labor force participation rate has declined from 23% in 2012 to 21% in 2018 (Ibid.). This decline has been attributed to a degree of discouragement by educated young women, as public sector employment opportunities – their preferred form of employment – have contracted. If this declining trend stabilizes or reverses, there will be further labor supply pressures in the upcoming decade.

What can the Egyptian government do?

What can the Egyptian government do to address this coming surge in labor supply and avoid an increase in unemployment rates?

First, it must maintain a fairly rapid rate of economic growth. Assaad (2022) estimates that growth rates in excess of 7% per year are necessary to create sufficient employment to maintain stable unemployment rates. Second, it must strive to transform the growth pattern into one that generates higher quality jobs that are suited for educated workers, especially educated young women. Egypt has relied excessively in recent years on the growth of infrastructure and real estate as a primary engine of growth (Amer, Selwaness, and Zaki 2021). This growth pattern generates low-quality jobs that are particularly unattractive to young women. The second stage of Egypt’s National Programme for Economic and Social Reforms aims to increase the relative weight of three economic sectors, namely the manufacturing sector, the agricultural sector, and the information and communications technology (ICT) sector (Ministry of Planning and Economic Development, 2021).

The ICT sector employment and increased demand

If successful, these structural reforms can go a long way in creating the sort of employment that meets the expectations of educated new entrants. The ICT sector, in particular, has seen large increases in labor demand in recent years and has been particularly hospitable to women. According to Selwaness, Assaad, and El Sayed (2023), although the share of ICT jobs in total employment has been small (1.8% in 2021), private sector employment in such jobs grew rapidly, at a rate of 5.5% per annum, well above the 2.1% per annum growth rate of non-ICT jobs in the 2009-2021 period. While female employment in the private sector in non-ICT jobs has been declining at a rate of 1.4% per annum, it has been growing at the meteoric rate of 10% per annum in ICT jobs. Moreover, the educational composition of ICT jobs is much more heavily weighted toward educated workers, with up to 63% having tertiary education or above, and 28% having secondary or post- secondary education (Ibid.). This compares to 15% and 35%, respectively, in non-ICT jobs.

This suggests that the rapid expansion of the ICT sector, in particular, and the digital economy, in general, can create the type of employment that the large wave of increasingly educated workers soon to enter the Egyptian labor market would aspire to. Despite its currently small size, accelerating employment creation in this sector can help avert or at least mitigate the significant increases in unemployment that are the likely result of the echo generation reaching labor market in the decade starting in 2025.

References

- Amer, Mona, Irène Selwaness, and Chahir Zaki. 2021. “Labour Market Vulnerability and Patterns of Economic Growth: The Case of Egypt.” In Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa 2020. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- Assaad, Ragui. 2022. “Beware of the Echo: The Evolution of Egypt’s Population and Labor Force from 2000 to 2050.” Middle East Development Journal 0 (0): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17938120.2021.2007649.

- Krafft, Caroline, Ragui Assaad, and Caitlyn Keo. 2022. “The Evolution of Labor Supply in Egypt, 1988-2018: A Gendered Analysis.” In The Egyptian Labor Market: A Focus on Gender and Economic Vulnerability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ministry of Planning and Economic Development. 2021. “The National Programme for Structural Reforms: The Second Stage of the National Programme for Economic and Social Reform.” Cairo.

- Selwaness, Irène, Ragui Assaad, and El Sayed, Mona. 2023. “The Promise of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Jobs in Egypt.” Cairo, Egypt: GIZ, Egypt.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.