Gabriela Borz, Cristina Mitrea, Anna Longhini, Thomas Montgomerie, Rémi Almodt and George Jiglău from the University of Strathclyde and Babeș-Bolyai University, investigate the relationship between digital technology and electoral democracy through the DIGIEFFECT project

DIGIEFFECT is a Next Generation European Union (EU) research project led by Dr Gabriela Borz (University of Strathclyde, Glasgow and Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca) which investigates the risks associated with digital political campaigning in the EU.

DIGIEFFECT applies a risk governance approach to studying digital political campaigning across European democracies. Each activity undertaken during online campaigning involving digital technology or artificial intelligence (AI) can have various positive and negative consequences (risks) for citizens, society and democracy (Borz and De Francesco 2024).

Risk governance for digital electoral politics involves the awareness, assessment, prioritisation, mitigation and prevention of online risks as assessed at three levels: by the regulator, addressees of regulation, deployers and consumers of digital politics (citizens). A mismatch of risk prioritisation and management across levels can result in higher levels of exposure to misinformation, disinformation or malinformation. Risk mitigation and prevention can take various forms, depending on the reference point: regulation (national and transnational), self-regulation (political organisations and private organisations), interventions (civic organisations) and digital political skills (individual).

Digital political campaigning: Instruments and effects across European parties

Are parties heavily involved in digital political campaigning? To understand the position of political parties, we field the DIGIEFFECT party survey across 27 European Member States and the United Kingdom during the second part of 2024. Respondents from 140 political parties with parliamentary representation recognise that digital campaigning is now a daily activity. The most popular platforms for political parties across EU are Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and Google. Most respondents state that their party posts unpaid ads on Facebook several times a day (41%) and paid ads once daily (30%).

On average, party respondents perceive digital campaigning as a good avenue for political engagement, which is understood as attracting new members, engaging with members and sympathisers, or mobilising voters. The most important declared benefit or positive risk of digital campaigning for parties is reaching a broader electorate, increased candidate visibility and microtargeting or reaching specific audiences with tailored messages (Fig.1).

On the positive side, the DIGIEFFECT party survey report (Mitrea et al. 2024) reveals increased engagement with party members, voters, and sympathisers. 55% of these parties declare that they offer an online membership option, which has increased in number over the past few years. Parties mobilise member support by encouraging intra-party online communication (emails/internal discussion forums/bulletin boards for members), creating party support pages on social media platforms (and online party campaign content/adverts, such as video content, across Facebook and Instagram). Some parties also run dedicated online events and targeted ads for voters living outside the country (17%).

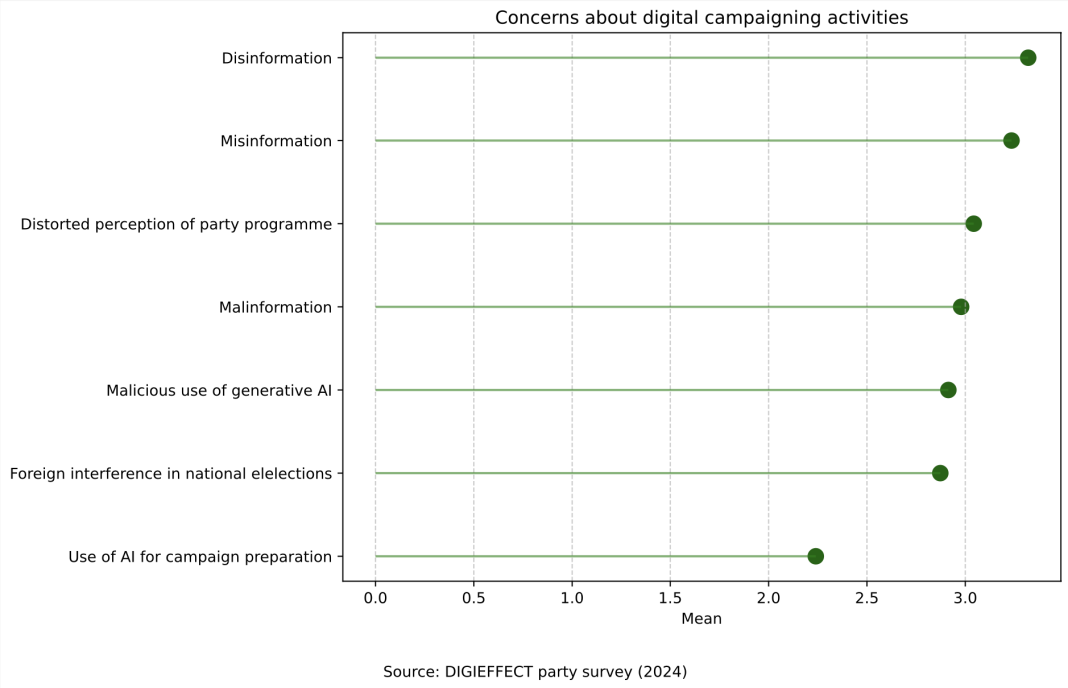

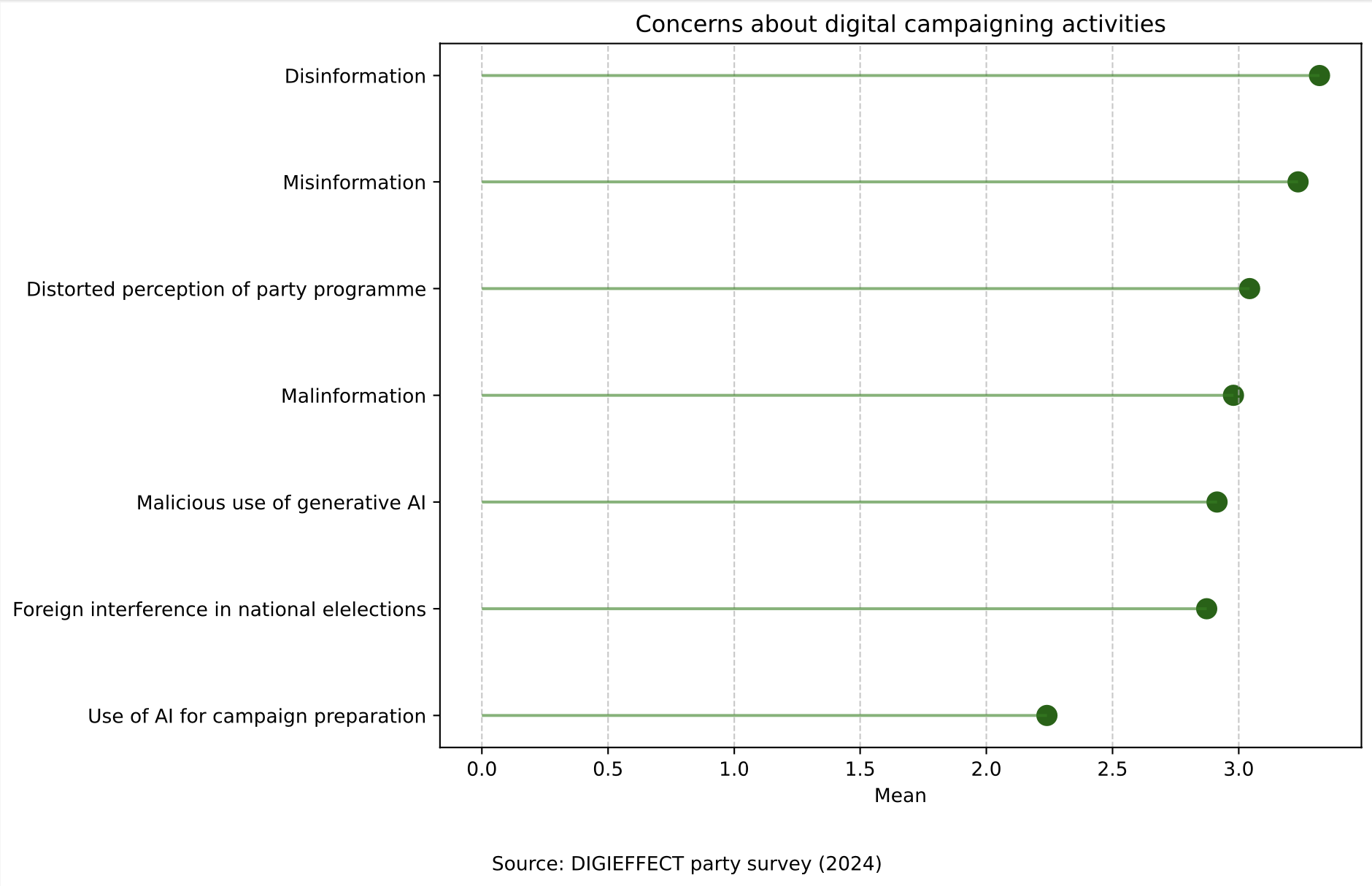

As far as the negative risks are concerned, party respondents are most concerned about disinformation (the intentional spread of false information with the intent to manipulate citizens), misinformation (the unintentional spread of false information on social networks) and distorted voter perception of the party program in the context of digital campaigning. The most common microtargeting practices acknowledged by parties (39%) include designing and producing online adverts specifically for groups based on location, political preferences, age and history of engagement with political content (Fig.2).

Other, more controversial targeting criteria, such as psychological traits or personality, have only been mentioned by few parties in our sample. Political parties address some of these risks internally by adopting internal codes of conduct (50%). Almost one-third of the parties in our sample (36%) show evidence of awareness of the need for disclaimers for their paid online adverts.

Citizens’ perceptions of digital electoral politics

Do citizens across different age groups understand the risks associated with online campaigning differently? Focus groups conducted in Germany, the United Kingdom and Romania investigate potential generational gaps. On one side, focus group participants show agreement concerning the high level of severity attributed to the risk of disinformation.

On the other side, disagreements arise concerning the preferred method for combating these risks. While younger generations point out to the individual responsibility to be informed and fact-check information, older generations consider that responsibility falls with governments when adopting the right measures against disinformation.

For example, citizens in countries like the United Kingdom express preferences for independent regulatory bodies. A forthcoming DIGIEFFECT cross-national citizen survey reveals citizen evaluation of risks, their mitigation and different levels of digital political literacy across Europe.

Regulatory instruments and practice across European countries and the EU

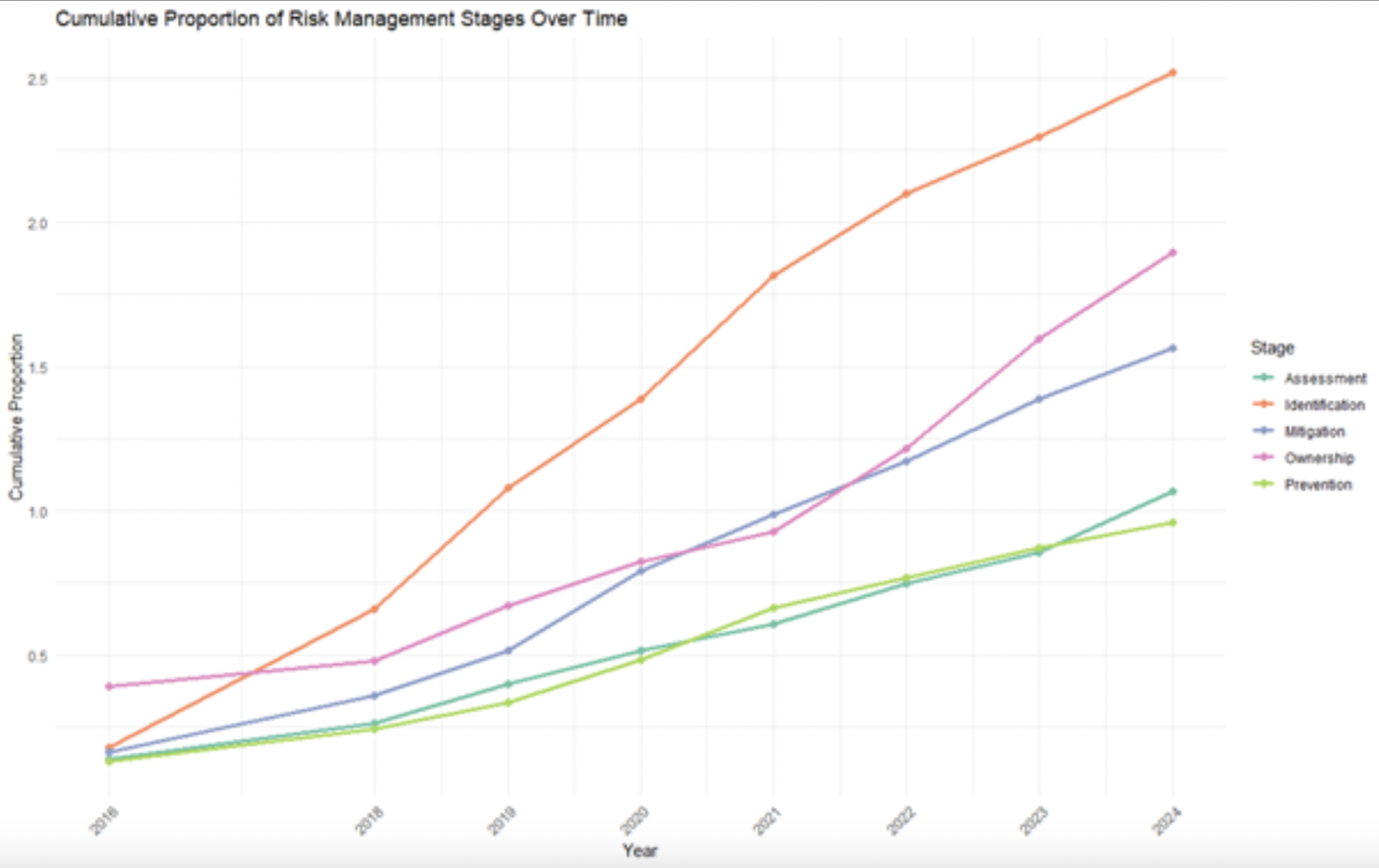

Positive and especially negative risks of digital electoral campaigning are not comprehensively embedded in national electoral laws or are non-existent. Out of 27 EU Member States, only 17 have legislation that references elements of digital campaigning. EU laws related to digital electoral campaigning have developed rapidly from 2016 to 2025 across a wide range of soft and hard laws. Overall, we observe an adaptaion from the EU as the regulator (Borz et al. 2025), in the sense of identifying the risks associated with digital campaigning but also in terms of mitigating risks. What needs more attention is risk prevention and risk ownership for increasing accountability (Fig. 3).

Bridging regulatory gaps in digital electoral politics

Understanding different perceptions, practices of digital campaigning by parties, compliance from platforms and evaluation from citizens helps address relevant regulatory gaps.

Firstly, as parties declare the use of alternative online platforms (Telegram, Viber, etc.) EU regulation could consider either reducing the cap for inclusion in the category of massive platforms (VLOPs) or adjusting its regulation accordingly to include smaller platforms. The category of risk owners needs to expand in line with the expanding plurality of actors involved in digital political campaigning.

Secondly, digital innovation in technology can go hand in hand with regulatory innovations: regulation needs to be adaptable to the new era of politics in the age of AI. Risk mitigation can work hand in hand with innovative policy designs, such as independent bodies, to check and monitor platform compliance with national and EU laws.

Lastly, as digital electoral politics will likely dominate elections in the future decades, the EU regulation could develop a uniform and less scattered digital electoral regulatory framework.

References:

- Borz, Gabriela, Longhini, Anna, Almodt, Rémi (2025) ‘Risk management and digital political campaigning: A computational analysis of European regulation’, DIGIEFFECT working paper, available at https://digieffect.eu/publications/.

- Borz, G., & De Francesco, F. (2024). Digital political campaigning: contemporary challenges and regulation. Policy Studies, 45(5), 677–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2024.2384145

- Mitrea, Cristina, Borz, Gabriela, Montgomerie, Thomas, Almodt, Rémi, Longhini, Anna (2024). ‘Digital Parties across Europe: Results from the DIGIEFFECT Party Survey’, DIGIEFFECT Research Report No. 1, available at http://www.digieffect.eu/publications.