Penelope J. Corfield from Royal Holloway, University of London, explores the symbolism of handshaking throughout human history

How do you reassure another person? Studies repeatedly show that holding their hand, firmly but unobtrusively, is an excellent way of doing the trick. It presumably reminds people subliminally of parental hand-holding and the trust that little children have (unless horribly disabused) in those who are caring for them.

Touching hands, in the ritualised form of greeting known as the handshake, is another adult form of reassurance. The gesture signals that two people are saluting one another, not as equals in everything – but as social equals at the time of greeting. The touching of their palms together, together with the light grip of their fingers, provides a mutual bodily pledge.

Of course, as already acknowledged, things could and did sometimes go wrong. Concord did not inevitably follow upon every single handshake. Nonetheless, the convention of regular handshaking spread steadily, initially in commercial Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

And as that happened, the sign of two linked hands – with palms pressed together – began to appear in various forms of popular symbolism. In effect, people were inventing their own heraldic devices. And to do that, they drew upon the increasingly familiar and reassuring sign of the handshake.

A diplomatic handshake in marble

It’s not possible to tally all the symbolic images of the handshake that appeared across Europe – or even simply in one country. The visual representations were so many and varied. And far from all have survived.

But one beautiful image confirms that the handshake retained its power as a pledge of peace. It’s found within the dazzling inlaid marble mosaic floor of Siena Cathedral. Among the many panels devised by local artists from the fourteenth century onwards is one showing a diplomatic handshake.

So who are the peace-makers? One is a furry she-wolf, the other a majestic lion. Both these potential predators are looking amiable. And their right paws are held out and gripped together.

Symbolically, the wolf is taken to represent the city of Siena; and the lion is its nearby Tuscan neighbour, Florence. Long may these two great cities flourish peacefully together! A good maxim for all times, recorded in mosaic marble.

Literary handshakes in print

Shaking hands were also used to signal shared mental endeavour. Printers of early printed books liked to cheer their readers by inserting small signals at the end of sections and chapters. These cheery page decorations (known by the French term as fleurons) often took the form of floral patterns.

Sometimes, however, little pictures were inserted instead. One popular end-section decoration showed a pair of shaking hands in close focus. It was as though the printer was encouraging the reader: ‘Greetings, my friend! Come and join me – and let’s share this intellectual journey together!

Certainly, a handshake was adopted as the symbol for one mid-European Literary Society in the early seventeenth century. This group met in Sopron, a regional centre in north-western Hungary, where they discussed books – and, no doubt, the latest literary gossip as well.

Moreover, the Society commissioned an elegant ceramic plate, to celebrate their efforts. It recorded the Society’s initials and the date (1604). And it featured centrally two lower arms, stretched out in a mutual handshake – whilst holding between their palms a printed document – probably a pamphlet. The message is one of shared friendship, with the joyful affirmation: ‘Look, the world of print is within our grasp!’

Fraternal handshakes on banners

In eighteenth-century Britain, meanwhile, public images of handshakes began to appear with increasing frequency. For example, the London’s Hand-in-Hand Fire Insurance Society (founded in 1696) issued lead wall tokens (some still visible today). These featured a handshake – indicating mutual support – and a crown, signifying the Society’s commercial respectability.

Over time, meanwhile, one of the most visible uses of the handshake was on banners of the fast-growing trade union movement. Workers began to negotiate – sometimes peaceably, sometimes aggressively – with their employers.

Trade union slogans urged that ‘Unity is Strength!’. Activists used fraternallanguage, addressing fellow workers as ‘Brothers!’ And their banners, which were paraded through the streets as moving bill-boards, often featured handshakes. They symbolised not only mutual support but also the vital need for solidarity.

For example, the resplendent red-and-gold banner of the National Union of Mineworkers (Elsecar Branch, Yorkshire) showed two men shaking hands over the legend ‘We Unite to Assist Each Other’. Or take the red-and-green banner of the National Builders’ Labourers & Constructional Workers Society (Walworth Branch, founded 1889): it showed four men exchanging two crisscrossing handshakes, making a mesh of solidarity. And the legend? ‘Workers Unite for the Common Case! Solidarity Means Victory’.

The symbol image of two hands gripped together in friendship remained current in publicity for the labour movement, from its origins until today. A later twentieth-century poster, produced by the California Teachers Union, shows a close-up of a handshake – with rays of power emanating from the image. And the legend again? ‘The Union Makes Us Strong’.

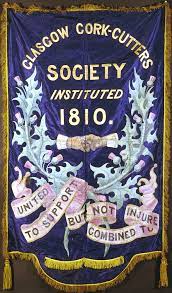

Interestingly, however, some activists were aware that power for one group might alarm others. Hence, the magnificent blue, silver and gold banner of the Glasgow Cork-Cutters Society (instituted 1810) [see Fig. in column 1, above] showed – yes – a handshake. But the legend explained soothingly that these workers were: ‘United to Support but Not Combined to Injure’.

Humanity’s handshake?

Needless to say, it’s hard to unite everyone. Nonetheless, the handshaking symbolism was sufficiently potent to be adopted in the 1790s by Britain’s campaigners to abolish the trade in enslaved Africans.

To arouse public opinion, the abolitionists wrote tracts, issued posters, and circulated small coin-like tokens. One of those showed a kneeling African, in chains, with his hands raised in entreaty. He asks: ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’

Appealing to common humanity was a bold move – and eventually, the abolitionists did swing British opinion against the trade. And the obverse of the token? Yes, it showed a handshake, surrounded by the words: ‘MAY SLAVERY & OPPRESSION CEASE THROUGHOUT THE WORLD!’ It is a great aim, even if hard to achieve. But let all humanity shake hands on that!