Professor Ingela Naumann at Fribourg University discusses the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on childcare arrangements and family wellbeing, and how it highlighted gendered care norms

The COVID-pandemic put a spotlight on a central conundrum of modern society: you cannot do your job while simultaneously looking after your child. Whatever you do, in the long run one or the other will suffer: You can park your child in front of the TV so you can do that online meeting (bad educational value!), or you pretend to be present in that meeting while, actually, you are stacking blocks with your child (and you might miss that important part in the meeting for your input!). Yet, during COVID-lockdowns when childcare services and schools were closed and employment moved online for many, scores of parents tried to do exactly that: juggle employment and childcare in their homes, all at once. How did they fare?

How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect the childcare arrangements and wellbeing of families?

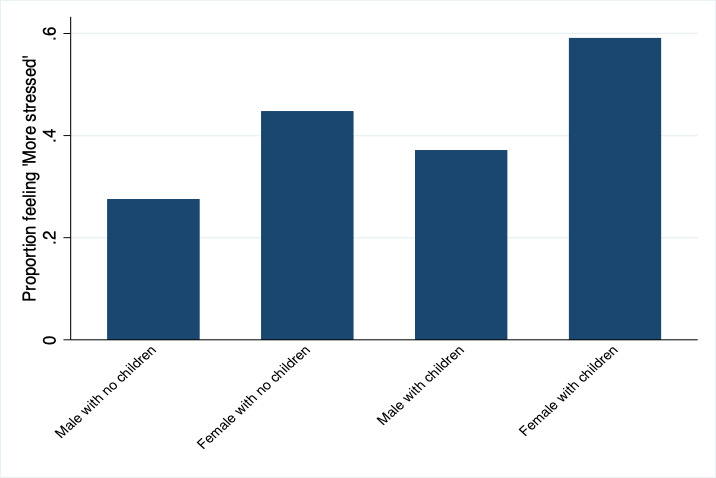

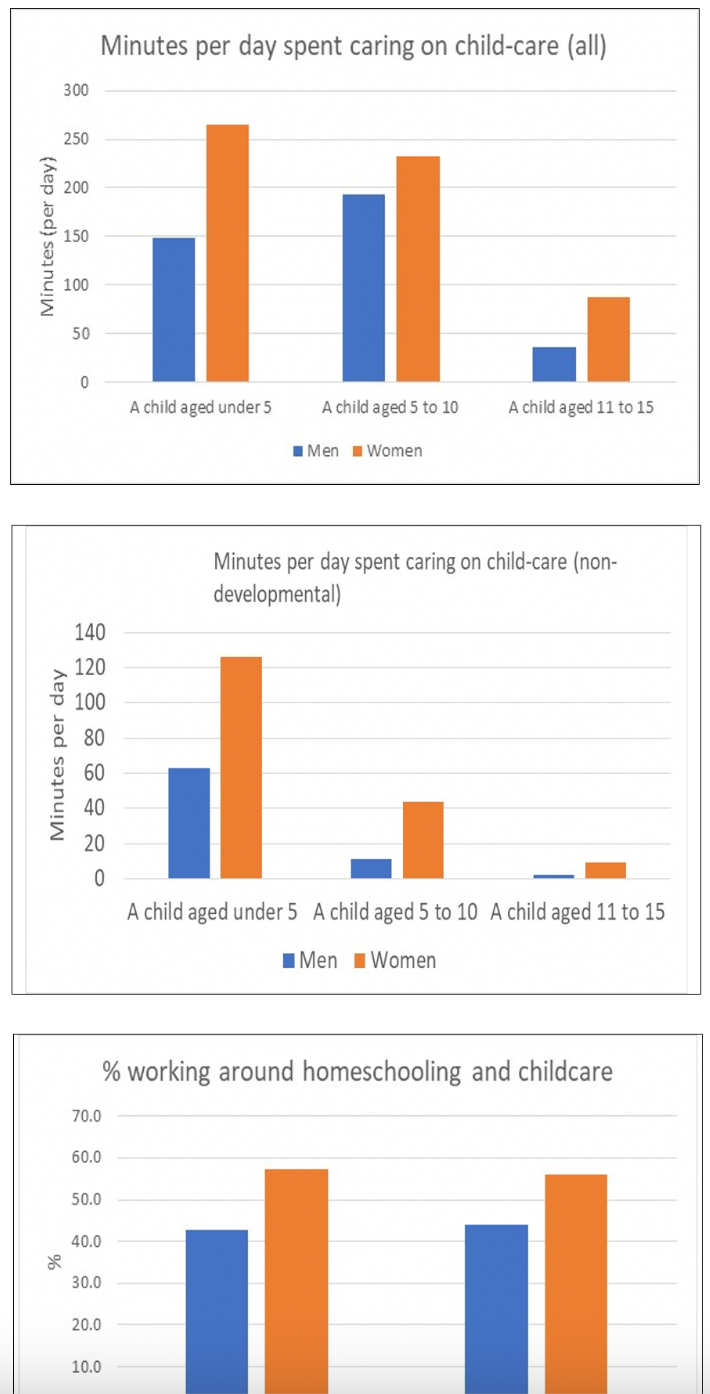

In a UK-based research project that analysed representative data from several longitudinal surveys and conducted interviews with a large number of parents on their experiences during the COVID- pandemic, we found that stress levels and exhaustion amongst parents rose significantly as a consequence of their continuous “multi-tasking”. Parents were more at risk of mental health problems during the pandemic than non-parents, and the worst affected were mothers (Naumann et al 2022).

There is a clear gendered picture to the pandemic: it was women who shouldered the extra demands of increased childcare responsibilities, homeschooling and more hours of domestic work, many juggling these with paid employment. What’s more, many women experienced a “double whammy” with increased employment demands, for example as nurses and care workers. It was also mostly women who cut back on their working hours or quit their jobs where it was not possible to combine the multiple pressures, for example in large families with several children or in one-parent families. Notably, we also found that where mothers suffered a sharp decline in their mental health also their children were at risk of poorer mental wellbeing (Naumann et al 2022).

Women in the UK are not alone in their experiences, research from around the world corroborates these findings (Seedat & Ronda 2021). The gendered costs of the COVID-pandemic were experienced on a global scale.

Why good childcare services are so important for society

While the COVID-pandemic and the measures needed to contain the virus such as social distancing were new experiences for us all, the challenges involved in juggling work and care responsibilities are not, of course. The COVID-pandemic only exacerbated what is for many parents, particularly mothers, an everyday struggle – and thus reminded us of the importance of good, affordable, and accessible childcare services.

Good childcare services can support parents in engaging in gainful employment and thus bolster families against economic insecurity; they can mitigate that “double shift” that parents, particularly mothers, cope with, thus supporting better health outcomes for parents as well as for their children. And finally, good quality childcare services support early childhood development and can thus help address the educational attainment gaps often experienced by children from disadvantaged backgrounds. That is why “childcare” these days has been replaced by the term “early childhood education and care” (ECEC) – to emphasize this double function with respect to parental employment and early education.

Women are caught between employment ideals and gendered care norms

As mature welfare states have begun to model reforms to their social security systems around the guiding principle of the “adult worker model” which links social benefits closer to contributions made via gainful employment, well- developed universal ECEC provision becomes even more central. For those members of society who cannot fulfil the “adult worker norm” due to care responsibilities are disadvantaged and at risk of financial insecurity such as old age poverty. This affects particularly women due to providing the bulk of unpaid care in society.

Only few countries have universal ECEC provision fit to fully support parental employment

Across the OECD, countries have begun to recognize the importance of ECEC to society and expanded its provision over the last decades. However, to date, only a small group of countries can be said to have developed ECEC systems that are fit to fully support parental employment – led by the Nordic countries that acknowledged the systemic role of ECEC early on, in the 1970s. Meanwhile, in most OECD countries, there still exist considerable gaps in ECEC provision, particularly for children under the age of three and with respect to affordable full-time services (OECD 2020).

To take developments in the UK again as an example: while an entitlement to 30 hours of ECEC has been introduced for children aged 3 and 4 (in England, Wales and Scotland), no such entitlement exists for Under-3s. Parents who need childcare services for younger children or need more than 30 hours for 3-4 years olds to match full-time or longer part-time working hours have to rely mainly on private and expensive childcare services, with low public subsidies. The recent Coram Childcare Survey found that a full-time nursery place for a 2-year-old costs on average as much as 50.2% of average full-time pay in the London area (and 35.5% in Scotland) (Coram 2023). This is unaffordable for many families, and particularly mothers are being “priced out of employment” having to give up their job or reduce working hours.*

Why childcare is key to gender equality

In light of the persistence of gendered care norms in most societies that became so apparent during the COVID- pandemic, a lack of affordable and accessible childcare services remains a serious obstacle to gender equality, and negatively affects women, children and society at large. Further efforts to expand childcare provision and increase public funding are needed in many OECD countries.

References

- Naumann, I. et al (2022): “Child and Parental Wellbeing during the Covid-Pandemic”, Working Paper 1, 2022, UKRI Covid-19 rapid response project Childcare and Wellbeing in Times of Covid-19

- Seedat, S. & Ronda, M. (2021): “Women’s wellbeing and the burden of unpaid work”, BMJ 2021; 374: n1972

- OECD 2020: “Is Childcare Affordable?”, Policy Brief on Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, June 2020.

- Coram Family and Childcare, Childcare Survey 2023

* In acknowledgement of this situation, the UK Government just recently announced in its set to expand the 30 hours childcare entitlement to children aged 2 and 1.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.