Associative mechanisms linking a defective minipuberty to the appearance of mental and non-mental disorders: infantile NO replenishment as a new therapeutic possibility

Preterm is defined as babies born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed. There are sub-categories of preterm birth, based on gestational age:

- Extremely preterm (less than 28 weeks)

- Very preterm (28 to 32 weeks)

- Moderate to late preterm (32 to 37 weeks)

One in ten babies is born too early before 37 weeks of pregnancy have been completed. Sadly, according to the WHO, preterm birth is one of the largest single conditions in the Global Burden of Disease analysis since an estimated 15 million babies are born prematurely every year, facing not only an increased risk of mortality but also a considerable risk of a lifetime of disability, including learning disabilities and visual and hearing problems brought on by altered minipuberty.

In 2019, there were 5.30 million deaths among children younger than 5 years with the leading cause of death being preterm birth complications (0.94 million; 17.7%) followed by lower respiratory infections (0.74 million; 13.9%), and intrapartum-related events (0.62 million; 11.6%).

Preterm birth: the truth in the numbers

In addition, preterm birth contributes to vast socio-economic consequences.

The statistical data collected from 14 European countries, presented in the EFCNI report, demonstrate the enormous, and increasing, financial burden associated with prematurity in U.S. and Europe: $25.2 billion per year in U.S., 1.4 billion in France, 3.2 billion in the UK, 500 million in Germany, with the rest of the European countries sharing a similar financial burden.

This lifetime cost estimates only include infants with major neurodevelopmental disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy, mental retardation, hearing loss, visual impairments).

However, infants born preterm are also at risk for other long-term morbidities including asthma, learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder, and emotional problems, while as adults, they also have higher rates of insulin resistance and hypertension compared to those born at term.

Measures to prevent preterm birth on a global scale in a clinically significant way have so far been ineffective. It, therefore, becomes increasingly important to improve outcomes in those preterm infants currently being born, in order to reduce the global burden of the preterm birth-associated multi-comorbidities. To this aim, a better understanding of the association between gestational age at birth and various mental and non-mental pathological phenotypes could help us implement new approaches to prevention, restricting the deleterious effects of premature birth that burden preterm individuals throughout life.

Understanding minipuberty and its consequences

The first 1000 days after our birth are critical for brain development, with a substantial amount of morphological development and acquisition of function taking place during that time through dynamic processes that stay highly vulnerable to environmental stimuli.

Interactions between a small region of our brain called the hypothalamus, and peripheral hormones have been increasingly acknowledged to play a fundamental role in shaping infantile brain development. This neuroendocrine crosstalk becomes evident for the first time already in the first months of our lives.

It is known as “minipuberty” because it is characterized by the transient activation of a hormone-regulating mechanism that will be re-initiated during puberty. Minipuberty will enable the coordinated function of three different component structures: the hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads (HPG) resulting in the hormonal surge initially responsible for the maturation of the ovaries in females and the testes in males, but also steroidogenesis, including the production of the gonadal-related steroid hormones estrogens that will feedback onto the brain to signal the end of the neonatal period and allow the initiation of the new phase of postnatal brain development.

Exacerbated minipuberty is the hallmark of premature birth, and pre- clinically it has been recently proposed to lie at the origin of many major neurological and psychiatric disorders, as well as disorders affecting reproduction and metabolism.

“NO” being the answer to reduce long-term complications in premature infants?

Efforts to better understand the mechanisms underlying minipuberty have led to the identification of a key molecule, a gas naturally produced by the human body, called nitric oxide (NO). Deficiency in NO production in both humans and mice has been associated with an abnormally exaggerated minipuberty profile accompanied by a series of reproductive and non-reproductive comorbidities, like fertility, metabolic, olfactory and learning disabilities. Remarkably, preclinical replenishment of the NO levels during the infantile period not only corrected minipuberty but also rescued sensory, and cognitive development in the long-term.

Interestingly NO is already given to the clinics for premature babies being under respiratory distress at birth. Hence, based on the above data the miniNO-project was set in motion along with a clinical trial aiming to verify whether preterm babies receiving NO will experience normal minipuberty and develop fewer sensory and neurological complications.

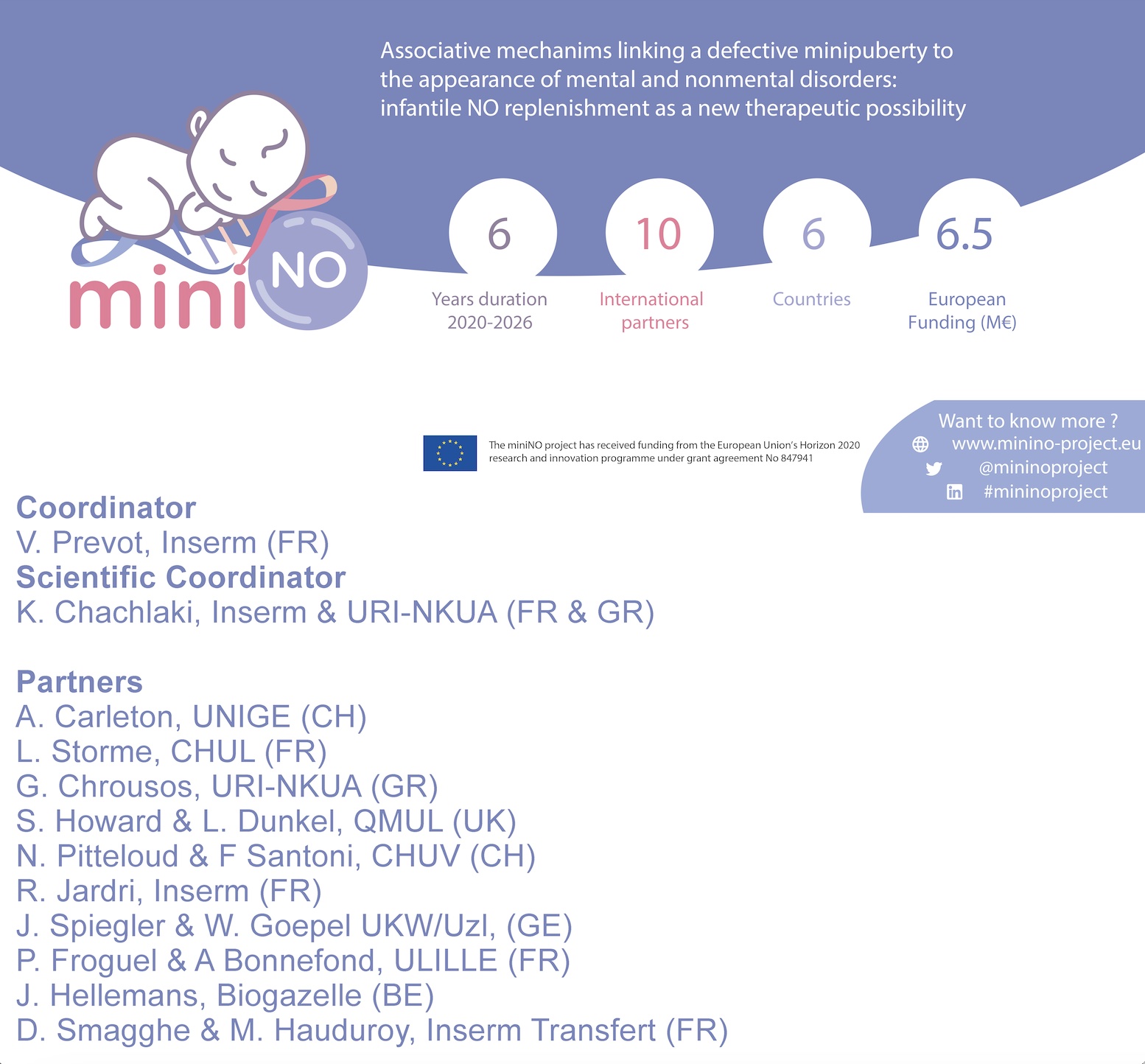

The miniNO-project

The miniNO-project, a European funded research initiative (H2020), is a high-impact project coordinated by Vincent Prévot, a neuroendocrinologist working for the French national health research institute (Inserm), in Lille, France, who along with the Scientific Coordinator Konstantina Chachlaki have put together an interdisciplinary and multinational consortium of neuroscientists, clinical scientists, paediatric and adult endocrinologists, psychiatrists and neurologists, geneticists, and genomic experts as well as a pharmaceutical company, committed to the same goal as a single functional unit. Together those 11 teams aim to provide the scientific and medical communities with a better understanding of how the physiology of the reproductive system early in life is linked to and affects other key neurological and bodily functions.

miniNO holds promise both for the early detection of premature infants at risk of developing mental and non- mental multimorbidity and for the development of a specific and harmless treatment for these conditions during a brief time window of infancy. If successful, miniNO will improve the quality of life of millions of prematurely born individuals, as well as alleviate a significant financial and societal burden in Europe and worldwide.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.