Remodelling palliative and end of life care requires different ways of working, different partnerships and a sharing of power

Global ageing means that death is now most commonly an event of older age. For most older people, the nature of living and dying in later life will be frailty and multimorbidity (MM – the co-existence of two or more long-term conditions).

Frailty is age-related and describes the gradual loss of inbuilt physiological reserves that leads to sudden, potentially fatal health deteriorations following seemingly small events, such as a minor infection. Frailty and MM increase the risk of dying in older age; those with severe frailty are five times more likely to die within a year than non-frail elders. However, the fluctuating progression of frailty, often over years, can make it hard to proactively identify when an older person is in their last year of life which is often a marker used as a referral to palliative and end of life services. Access to palliative care for all people with life-limiting conditions is recognised as important at the highest policy level. However, the experience of older people nearing the end of their lives is often poor. Many older people risk over-treatment to prolong life, and under-treatment from palliative care; actively addressing quality of life and person-centred needs and care goals, when a cure is not possible, is too often poorly handled.

Providing end of life care for older people – moving beyond prognosis

Prognosis, estimating when someone is likely to die, can help to facilitate future care planning conversations and support patient-centred care goals and conversations with loved ones. However, the assumption that time to death should, and can, trigger end of life care is problematic. Evidence suggests accurate prognosis is difficult: overestimation is common and temporal estimates are mostly inaccurate. Prognostication is particularly difficult in older adults with frailty, where there are no standardised and evaluated models and markers to support end-of-life identification. Time-based approaches for referral to end-of-life/palliative care services are increasingly questionable. Rather, end-of-life care provision for older people should be focussed on a holistic formal assessment of need and tailored care. This is the focus of the University of Surrey’s Living and Dying Well research programme.

“Living And Dying Well” research

Our work is focused on the duality of older people living and dying well over a life long-lived. Currently, older people with frailty too often fall between services either focused on living independently or imminently dying. Our work has evidenced the centrality of any end-of-life care responses to take account of the strengths and capabilities of older people, including their social connections, as well as any potential and actual vulnerability. All too often, care interventions can leave an older person feeling trailer, experiencing a sense of being “done to” rather than “cared about”. We focus on older people living at “home”, the place of preference for most older people. Core Activities include:

Evidencing specific needs and tailored care for older people at end of life

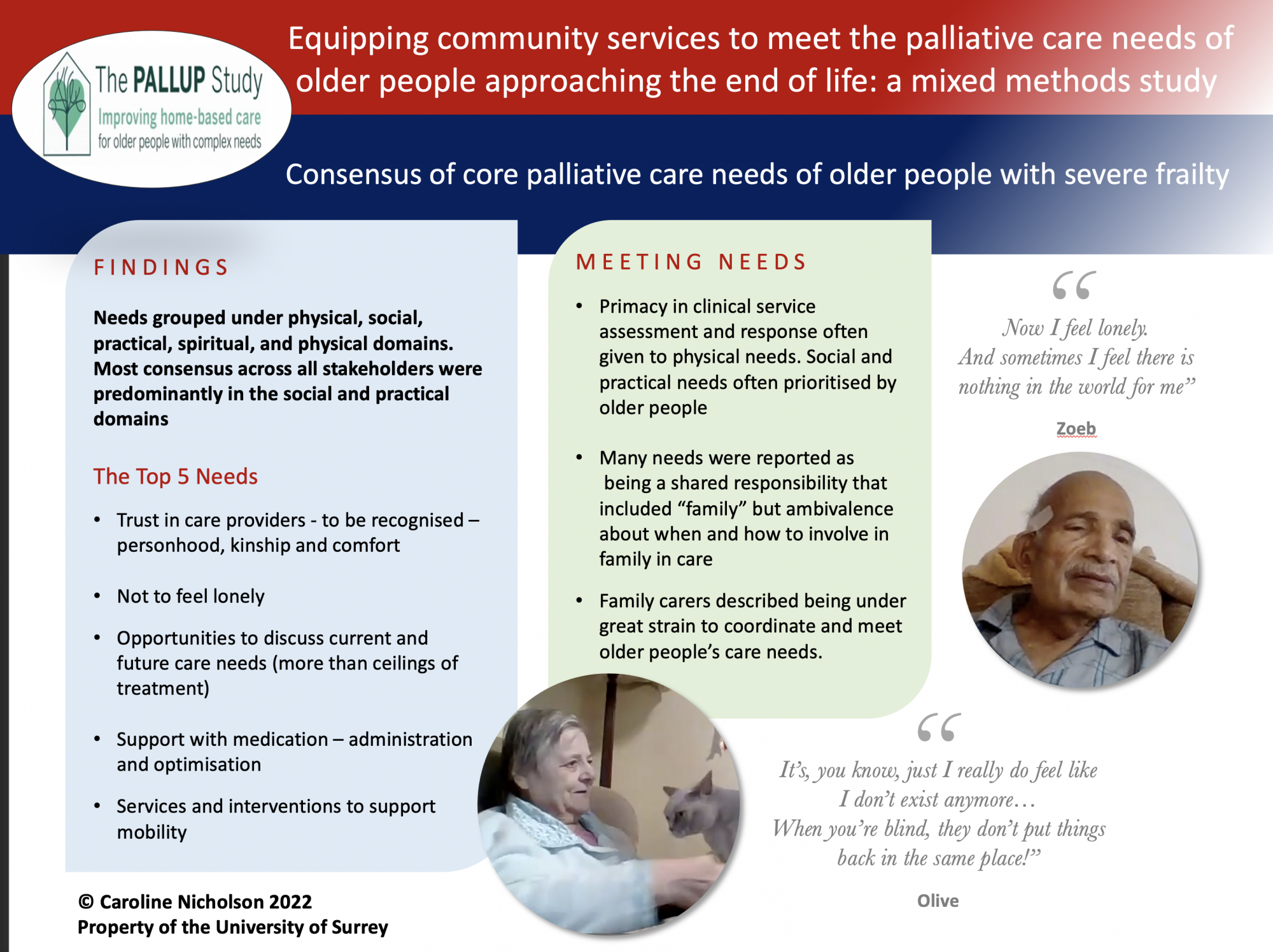

The HEE/NIHR funded PALLUP study evidences the specific end-of-life needs of older people with frailty and current service responses. This evidence will be translated with key stakeholders to develop a service framework and resources to support tailored care. A scoping review of published literature evidencing the perspectives of older people with MM supported a consensus exercise to gain agreement on the core needs of older people with frailty at end of life.

Data from facilitated virtual interviews with older people and their families and a two-round online survey with health, social and voluntary services and family carers was analysed. Needs were grouped under physical, social, practical, spiritual, and physical domains. Most consensus across all stakeholders were predominantly in the social and practical domains. The Top 5 identified needs were, 1) Trust in care providers – to be recognised as a person 2) Not to feel lonely 3) Opportunities to discuss current and future care needs 4) Support with medication – administration and optimisation 5) Services and interventions to support mobility. Key to meeting needs were the role of family carers who were often unsupported and under great strain.

The PALLUP film trailer can be accessed here and the full film by completing the film registration form here.

Reconfiguring and resourcing care services including “family”

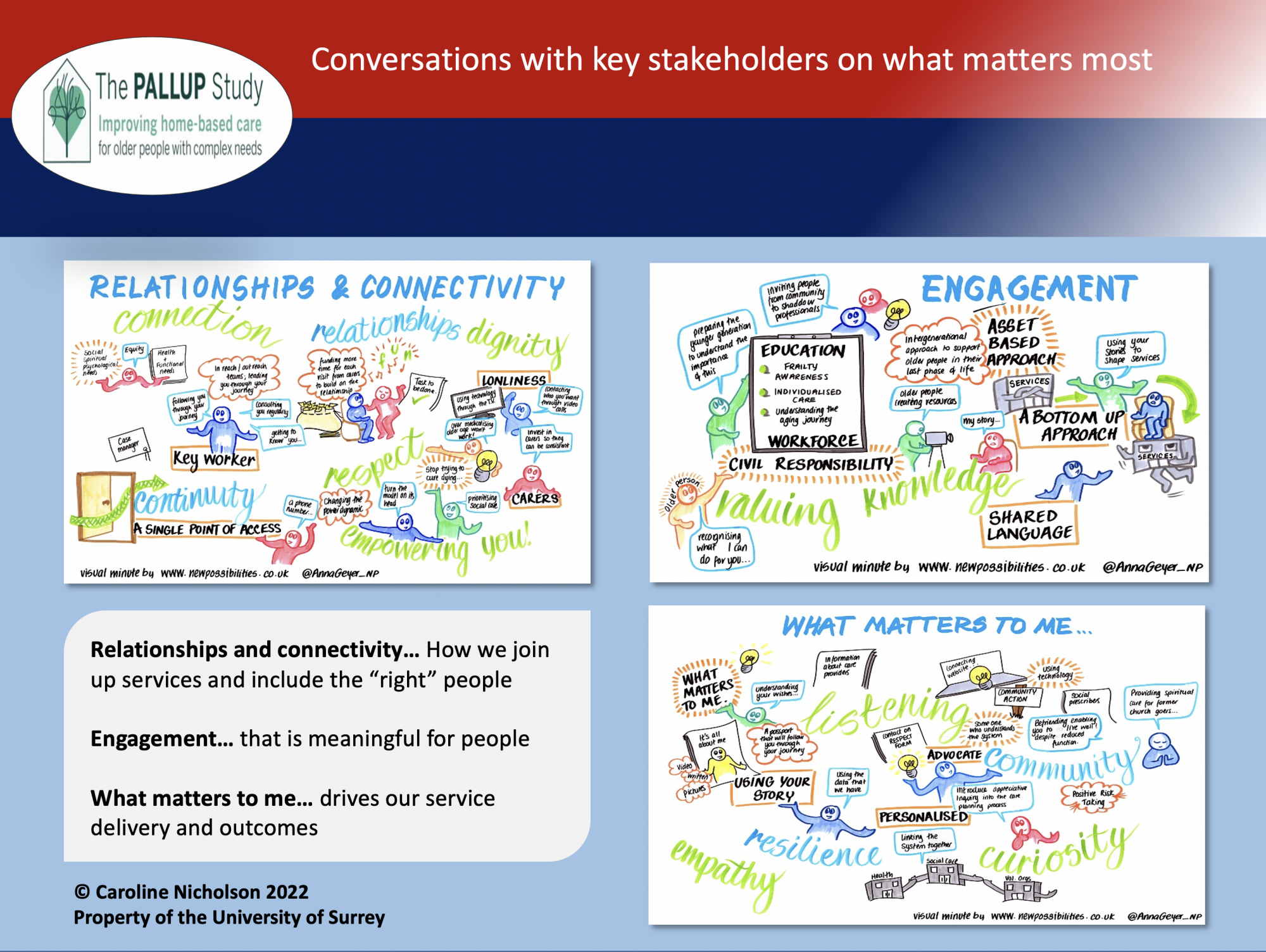

The NIHR Palliative and End of Life Care Research Partnership is working in 3

areas in England to grow a research partnership of care providers across sectors that will improve the coordination of end-of-life care for community-dwelling older people living with advancing frailty. Social, voluntary and health care, and representatives of older people and family carers are involved. Resourcing services includes developing tailored tools to support older people and their family to articulate their needs and for these to drive care provision. The Pro-frail study will develop a PROM/PREM specifically addressing the needs of older people with frailty in the community.

Our work is also developing resources to support the increasingly essential role that family or, perhaps more accurately, unpaid carers, play in the care of older living in the last phase of life. The dual expert study is supporting family decision-making at points of uncertainty.

In conclusion: end of life opportunities and challenges

It is a source for great celebration that most people will live and die in older age. In England, new legislation denotes that end of life care is no longer a sub-speciality, but a universally required service. There is a moral and clinical imperative for palliative care services to contribute to the support of people with frailty and MM as they near the end of their lives. Remodelling of palliative and end of life care services requires different ways of working, different partnerships and a sharing of power to enable a focus more on need rather than diagnosis and prognosis.

For references please see here.

Contributors – Dr R . Green, Dr, S Combes and Ms F. Howard – University of Surrey.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.