The intrinsic value of the partnership between agriculture and social welfare sectors can help us to enrich the way that we work, and how we think about work

As an equivalent to what is called “social farming” or “care farming” in the West, the term “partnership between agriculture and social welfare” has now entered the regular Japanese vocabulary. The advocates emphasize its advantage of linking the shorthanded agricultural sector with the people excluded from the existing labor market by offering job opportunities to them. The article in the preceding issue illustrated that the intrinsic value of the partnership between agriculture and social welfare is not limited to such an advantage, mentioning my own initiative targeted at homeless laborers and young trainees receiving employment support. However, I also faced several challenges, which may be inevitable when urban dwellers without rural background attempt farm work.

Source: Tsunashima, H. (2018) What is necessary to enhance autonomy of laborers in activities toward cooperation between agriculture and human welfare?, Japan. J. Agric. Educ. 49 (1): 1-13 (Transted from Japanese and partly modified).

What is it to grow crops?

What differentiates farm work from other occupations is interaction with life forms other than humankind for the purpose of growing them. This cannot be as easily managed as inanimate materials used in other industries, since even a flock of life forms has a variety of characteristics. Thus, the individuals have different responses to approach of their grower, which means that some, if not all, of them, will inevitably deviate from the grower’s intention. And moreover, it takes time for them to respond to the grower’s approach. To illustrate, the farm task of sowing is aimed at germinating seeds, but growers cannot but create a favorable environment for germination and then just wait for it. There is no guarantee that all of their seeds will be successful.

Therefore, growers will need to observe whether the aim has been achieved after a certain period of time. Without such an observation, they cannot make a decision on the following task in any detail. In other words, the act of growing crops repeats, execution of a farm task, observation of its result, and decision-making on the next, in a cyclical nature. If observation results accord with what the growers expect, they will deepen their self-confidence; however, the opposite sometimes occurs to require them to reconsider their prior activities. Either way, observation results evoke some emotion in them, leading to endless trial and error, with a sense of excitement as well as the development of their farming skills. As will be elaborated in later issues, something lurking behind this process has a potential for promoting the genuine well-being of citizens in urbanizing society.

Incompatibility with job creation and employment assistance initiatives

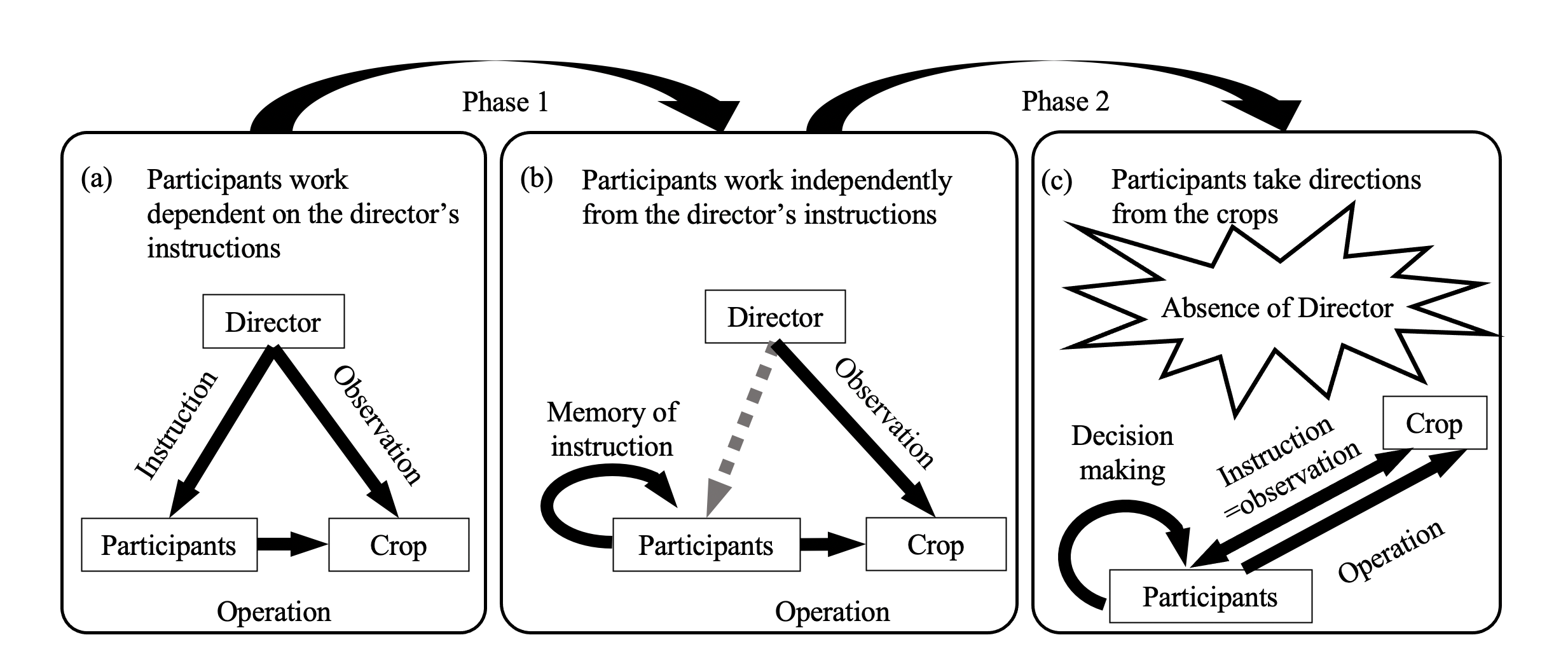

However, participants in my project appeared to consider that to work is to follow instructions given by their superiors. As was usual, their director in the farm should make such observations, and based on which, give them instructions. Apparently, they were flinching from becoming independent from their director. They always hesitated to observe various changes in the field to judge whether or not to execute every task. The series of hurdles was a two-step transformation of the tripartite association among participants, director and crops; the participants become independent from, or see ahead of, the director’s instructions based on their memories, in the first phase, and later on, they become able to read some signs in what the crops show, or “take directions from the crops” in the second one (Fig. 1). From this viewpoint, what remains unsettled at present is how to enter the second phase with a qualitative change in spontaneity.

Latent in this problem might be an ascetic attitude of participants toward paid work. During the interviews or when working with them, they suggested to me that they should not seek pleasure through wage labor because they were paid for toil. They would actively anticipate, rather than wait, their director’s instructions, sometimes reading his expression. This was the case, especially with the elder homeless, who had formerly worked as regular employees or day laborers. It seemed that they wanted to work for someone as wage laborers to the end. To put it differently, since they had been excluded from the ordinary labor market for many years, they were eager to follow someone’s instructions in a bid to restore the commercial value of their labor that had been denied for a long time. These findings demonstrate that it is extremely difficult to provide them opportunities to enjoy observation on the growth of crops while paying them wages at the same time.

Searching other cases for a clue resulting in a counterquestion

To address this new problem, some progressive partnership cases were examined in search for clues. For each case, I conducted an interview with the director, who was in charge of giving instructions. However, they did not expect participants to make observations explicitly. Some of them said that all they are required to do should be what they could do then, despite the fact that some participants exhibited their autonomy. Even on those exceptional occasions, the potentially autonomous farmers could not tell what constituted such autonomy. Looking this result from a different angle, I found myself the only one who was particular about autonomy – I am required to clarify the reason why I was.

My answer to the current counterquestion would be as follows: The salient characteristic of farm work consists in a simple fact that growers take directions from the crops or livestock, over which human beings should wield absolute power. The difficulty in farm work for urban dwellers mirrored the oppressive characteristics of the existing labor market and the manner in which they have tried to adapt themselves to it. Making close investigation into this challenge, we could enrich our ideas about how we can work. Once wage labor incorporates the aesthetic experiences which the other life forms offer to their growers, what we have been taking for granted cannot remain intact. And then, the intrinsic value of the partnership between agriculture and social welfare sectors will

become clear.

Acknowledgement: Publication of the present article was supported by the TOYOTA Foundation.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.