Associate Professor Mariken A.C.G. van der Velden at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam discusses how political compromises can hinder affect a functioning democracy

Key to a functioning representative democracy is political parties competing based on alternative policy ideas to improve society during campaigning periods and the very same political parties cooperating outside these campaign times. While this holds for all forms of democracy, the tension between conflict and cooperation is particularly acute in Europe’s multiparty democracies with coalition governments.

On the one hand, political parties in a coalition government must maintain a degree of loyalty to their own supporters to remain viable political entities. This means that they must advocate for policies and positions that are consistent with the values and beliefs of their core constituencies.

On the other hand, parties in a coalition government must also be willing to compromise and work collaboratively with other parties in the coalition. This often requires them to make compromises on policy issues by supporting policies that may not align perfectly with their own party platforms. Compromises are thus a defining characteristic of representative democracy.

Political compromises do not come without their challenges

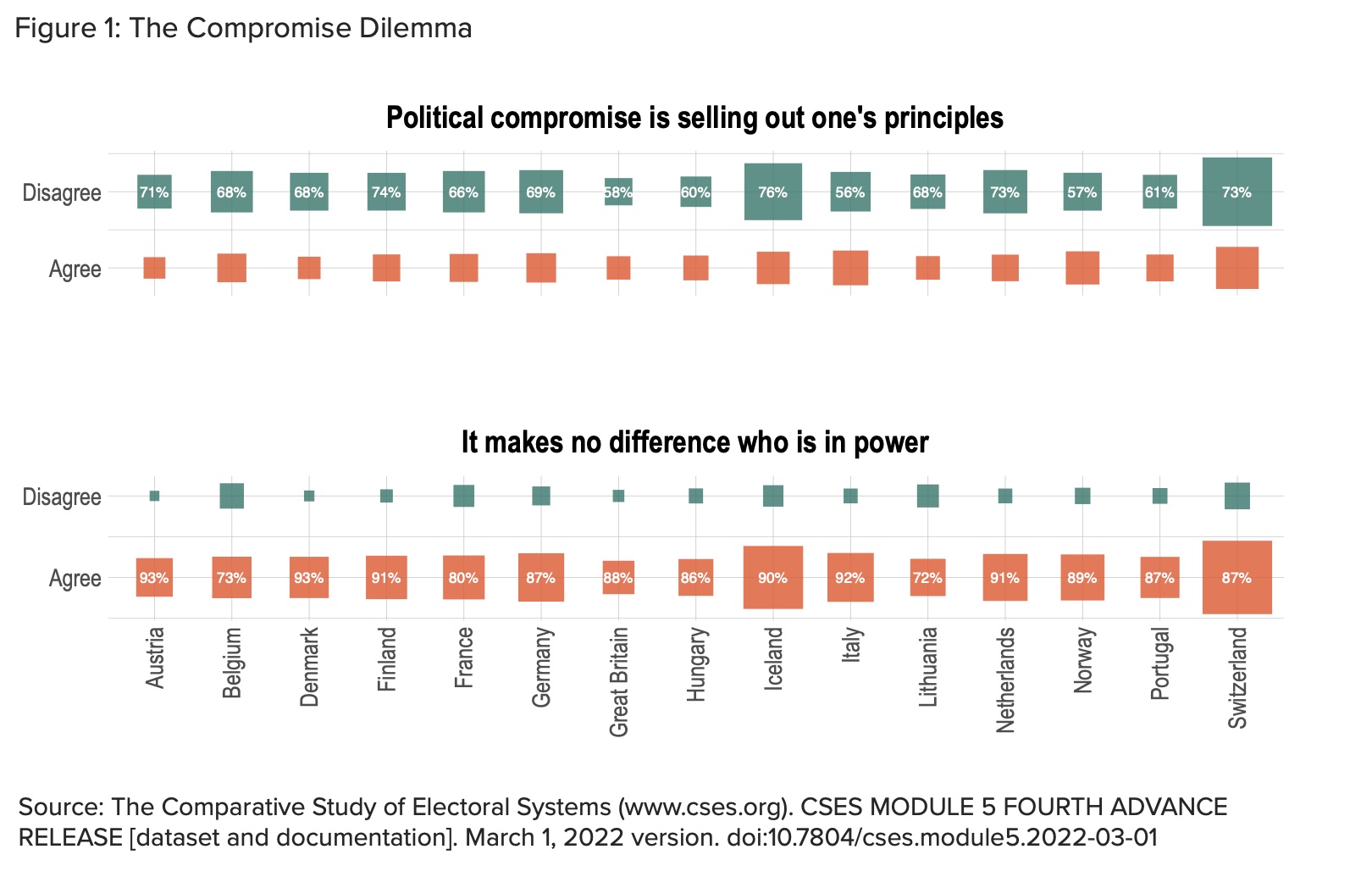

While key to representative democracy, political compromises do not come without a set of challenges. First, they potentially undermine citizens’ satisfaction with the procedures in democratic systems. Regardless of the political system or the ideological stripes of the government, we see a broad consensus in Europe about the support for political compromises. When voters are asked whether when a politician or political party is striking a compromise, they are selling out their principles, and they overwhelmingly disagree. The top panel of Figure 1 visualises this: 60% or more of voters do support the democratic principle of compromise.

Countries that have a stronger two-block system or where political polarisation is higher, such as respectively Great Britain or Italy, this percentage of voters’ support is just slightly under 60%, but in countries with a coalition tradition, such as Austria, the Netherlands, Iceland, or Switzerland, the approval rate for political compromises even goes up as high as three-quarters of the voters.

However, at the same time, the bottom panel shows that when asked about the effectiveness and distinctiveness of a government in their respective countries, people overwhelmingly agree that it makes no difference who is in power, most likely due to the diluting effect of political compromises. When political parties play a tit-for-tat strategy to realise some of their electoral pledges or when they give in to another party for the sake of governability, that party downplays its ‘ideational commitments’. That in turn could lead voters to perceive that there is no difference between political parties and that, when it boils down to it, the spoils of office are valued over the commitments pledged during the campaign.

How does this affect citizens’ trust in democracy?

In my research, I show that this experience, coupled with the rhetoric of populist party leaders and conspiratorial influencers who sew fertile ground for thinking that politicians lie to “the people” and deceit them, affects citizens’ trust in democracy. How politicians communicate about the decisions they make, whether staying put or compromising is key to addressing the compromise dilemma.

The second challenge is the so-called “paradox of compromises’’: The striking difference between individuals’ support for the democratic principle of compromise, as shown in the top panel of Figure 1, and their actual willingness to accept compromise. Voters prefer uncompromising political actors, while also demanding that they step up to govern the country.

Source: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 5 FOURTH ADVANCE RELEASE [dataset and documentation]. March 1, 2022 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module5.2022-03-01

What interferes with accepting compromises?

In general, the usage of persuasive arguments and positional commitments, as used in campaigns, imperils accepting compromises as it reminds one that there is something to lose. Four trends in society contribute to politicians increasingly using such a persuasive and positional rhetorical style. First, a changing media landscape allows politicians to communicate directly to the world without the traditional gatekeepers of the press contextualising their communication.

Second, increased levels of affective polarisation make people from different ideological stripes less willing to accept cooperation with ‘the other side’. Third, increased ideological fragmentation necessitates politicians to cooperate with more others, as for example, two-party collaboration is often not enough anymore to get a majority in parliament. Fourth, and relatedly, increased volatility leads politicians to pledge accountability to voters, also in routine times of politics. Together, these trends have resulted in a permanent campaigning stage, where voters are reminded about the stakes and the potential to be electoral losers when their party compromises on its promises.

Is there a way out of political fragmentation?

In my work, I research the reputational cost of political compromises and their downstream effect on citizens’ perceptions of democracy. Across the board, I show that a part of the citizenry is no longer “just” discontent with (some of) the decisions politicians have made resulting in policies that do not align with their political preferences but question the legitimacy of politicians to make these decisions. Citizens see politics as part of the problem rather than the solution, I, therefore, argue that we need to bring back the fun in politics. One way of doing this is by means of gamifying political participation, using the full potential of media technology.

Gamifying political participation

Many scholars, pundits, and practitioners have argued that democracy needs a ‘booster shot’ in the form of innovative citizen participation initiatives (ICPIs), an umbrella term

for citizen involvement in public decision-making through, for instance, referendums and deliberative mini-publics. I have built virtual town halls, where people learn about and discuss political topics. Participating in such a virtual town hall debate using VR is a form of gamifying political participation. A gamification is a proven tool that can enhance levels of motivation and engagement by creating similar experiences to those experienced when playing video games.

It produces a novelty effect, the so-called wow factor, and thanks to the technology used, provides users with a near-realistic experience. This allows citizens to have a conversational give-and-take with other participants, including people they would not normally meet or engage with, and make political decisions based on orderly and respectful discussions. Results from my VR games so far demonstrate that gamifying political participation has the potential to reconnect people to politics. The people who participated in these games said that they had more of an understanding of the complexity of the political process, and therefore are more aware that not everything can

go their way.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.