Ragui Assaad from Humphrey School of Public Affairs, at the University of Minnesota, argues that structural reforms result in increasingly difficult and unequal school-to-work transitions for Egypt’s youth

Egypt adopted a series of structural reforms since the 1990s designed to curb the size of the public sector and place the economy on a market-oriented trajectory. While these reforms succeeded in shrinking the size of the public workforce from 39% of total employment in 1998 to 26% in 2018, they failed to ignite job creation in the private sector (Ragui Assaad, AlSharawy, and Salemi 2022; Amer, Selwaness, and Zaki 2021). The share of formal private wage employment in total employment increased marginally from 8% in 1998 to 12% in 2018, while overall employment failed to keep up with population growth (Ragui Assaad, AlSharawy, and Salemi 2022).

The failure of structural reforms to ignite job growth in the private sector led to an increasingly difficult and unequal school-to-work transition for Egyptian youth over the past three decades. Educated youth are increasingly unable to translate their education credentials into the middle-class jobs that their older counterparts could get with similar levels of education.

Furthermore, the allocation of good (formal) jobs has been increasingly driven by social class background, as the private sector is more prone to using social class markers as a way to sort through legions of applicants (Assaad and Krafft 2020; Assaad, Krafft, and Salemi 2022).

School-to-work transitions research

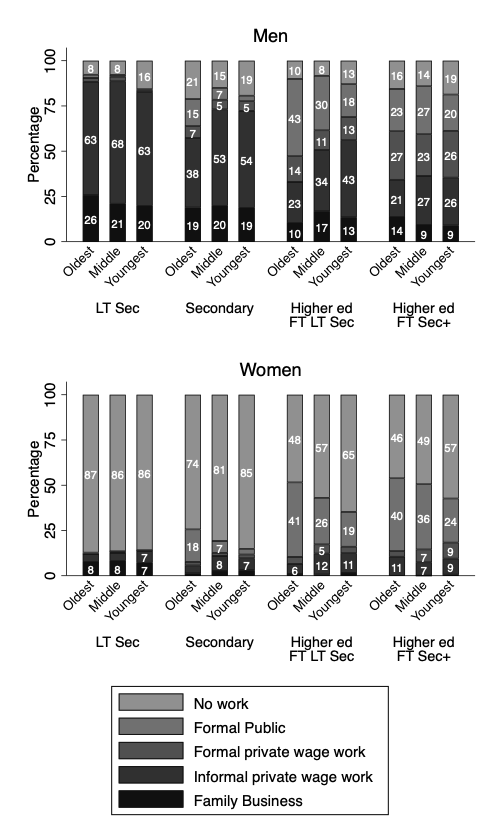

By analyzing the school-to-work transitions of three cohorts of youth in Egypt, Assaad and Krafft(2020) demonstrate how such shifts have changed for educated young men and women over time. The oldest cohort completed schooling in the 1980s, before the onset of structural adjustment policies. The middle cohort completed its schooling in the 1990s as these policies were underway, and the youngest cohort completed its education in the 2000s after the main structural reforms were adopted.

They also distinguish young people by their own educational attainment and, for those with higher education, by their socioeconomic status as indicated by their father’s educational attainment.*

This research shows that for those with less than secondary education, the school-to-work transition has mostly stayed the same across the three cohorts. As shown in Figure 1, young men with less than secondary education transitioned into various kind of informal employment, including family business and casual wage work, with little change in this pattern across cohorts. Similarly, most young women with less than secondary education do not transition into the labor market at all, again without much change across cohorts.

Notes: The oldest cohort completed schooling from 1980-89, the middle cohort from 1990-99, and the youngest cohort from 2000-09. FT LT Sec = Father with less than secondary education, FT Sec+ = Father with secondary or above education.

Source: Author’s calculation using Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey 2012 data.

School-to-work transitions across cohorts

The situation is somewhat different for young people with secondary and higher education who experienced substantial changes in their school-to-work transitions across cohorts. Young men with secondary education in the oldest cohort had a modest chance of transitioning into formal wage work (15% into public and 7% into private). Still, these chances dwindled considerably for the middle and youngest cohorts, whose vast majority are now relegated to various forms of informal work.

Similarly, the modest chance that secondary-educated young women had to join the public sector among the oldest cohort almost entirely disappeared when the youngest cohort attempted their transition.

The ability of young people with higher education certificates to negotiate a successful modern transition to formal employment increasingly depends on their socioeconomic status. As shown in Figure 1, young men in the oldest cohort who achieved higher education but who are from low socioeconomic backgrounds (their father having less than secondary education) were highly dependent on the public sector to achieve a modern transition; 43% transitioned into public sector jobs and only 14% transitioned into formal private sector jobs.

In contrast, their high socioeconomic counterparts were more or less equally split across the public and private sectors for formal jobs. As access to public sector jobs dwindled after structural reforms, only 18% of higher educated men with low socioeconomic status in the youngest cohort could obtain public sector jobs without increasing their ability to access formal private sector jobs. Like their counterparts with lower academic attainment, they were increasingly relegated to various kinds of informal work.

Those with higher socioeconomic status saw their access to the public sector decrease less and maintained relatively good access to private formal wage employment. Similarly, women with higher education and low socioeconomic status saw their transitions to public sector jobs dwindle across cohorts without any increase in access to formal private employment. Those with higher socioeconomic status saw a slight decline in access to public sector jobs and a substantially more significant increase in transitions to formal private jobs.

Public and private sector recruitment

The retrenchment of the public sector hiring in the wake of structural reforms in Egypt substantially reduced the ability of educated young people to translate their educational advancement into good jobs, but, as shown above, this was much more acute for those with low socioeconomic status because of their restricted access to formal private jobs.

The tendency of the formal private sector to use social class as a recruitment criterion could be a rational recruitment strategy if available information on workers’ productivity-related characteristics is limited and social class correlates statistically with such traits. How can policymakers ensure greater fairness in allocating good jobs in the economy short of resuming public sector hiring?

A concerted effort to improve the information job candidates can signal about themselves would go a long way in addressing this problem. This can be done by encouraging more extracurricular activities in educational institutions, increased opportunities for internships, and more volunteering opportunities; in short, ways to allow job seekers to differentiate themselves in the labor market on a basis other than social class.

Ultimately, however, the problem of the scarcity of good private sector jobs will only be solved through greater dynamism in private sector job creation, something that goes beyond the realm of labor market policies.

References

- Amer, Mona, Irene Selwaness, and Chahir Zaki. 2021. “Patterns of Economic Growth and Labour Market Vulnerability in Egypt.” In Regional Report on Jobs and Growth in North Africa 2020, edited by International Labor Organization and Economic Research Forum, 97–151.

- Assaad, R., and C. Krafft. 2020. “Excluded Generation: The Growing Challenges of Labor Market Insertion for Egyptian Youth.” Journal of Youth Studies. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13676261.2020.1714565

- Assaad, Ragui, Abdelaziz AlSharawy, and Colette Salemi. 2022. “Is the Egyptian Economy Creating Good Jobs? Job Creation and Economic Vulnerability from 1998 to 2018.” In The Egyptian Labor Market: A Focus on Gender and Vulnerability. Eds. Caroline Krafft and Ragui Assaad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Assaad, Ragui, Caroline Krafft, and Colette Salemi. 2022. “Socioeconomic Status and the Changing Nature of School-to-Work Transitions in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia.” ILR Review, December, 001979392211414. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00197939221141407

Individuals with less than higher education are primarily of low socioeconomic status, making it only necessary to make the distinction for those with higher education or above.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.