Marian Adriaansen and Henk Poppen from HAN University of Applied Sciences discuss their research on how Bachelor’s students in nursing coped with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID pandemic, nurses were called upon to maintain patient and self-safety and quality of care in stressful circumstances. Bachelor’s students in nursing were also initially confronted with a situation that was new to them, and they were unable to draw on previous practical experiences. The question was how they dealt with this situation and whether this led to more stress or to a more negative image of their profession.

Theoretical framework: Coping during COVID-19

The Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R model) was used as a starting point for the research among Bachelor’s nursing students.(1) This model assumes that high job demands lead to stress and ill health among employees, but that this stress can be reduced by using personal energy sources that can positively influence motivation and productivity.

This could mean for nursing students that they can make progress in their personal and professional development despite possible stress. Students followed internships or theoretical education. The stress of an internship is normally caused by a new environment (clinical placement or placement in the community), with new colleagues and a new type of client. The COVID pandemic has added new, unique stressors.

Theoretical training was characterized by intensive contact with teachers and fellow students but was now converted to mere online contact. This period may also influence their perception of the profession, but perhaps nearly a year of COVID experience will lead to different results in comparison with the start of the pandemic.

Tracking Coping during COVID-19: Method

An online questionnaire regarding their experiences and how they managed coping during COVID-19 was presented to third and fourth-year students of the full-time nursing Bachelor’s program on two occasions, in September 2020 and May 2021. The questions were based on the JD-R model and the Coping process model describing how people can handle stress. (1, 2)

In 2020, the coronavirus crisis was still new and took everyone involved by surprise. In the spring of 2021, students had already been in lockdown for a year, and both the program and the field of practice had found a way to deal with this. During both COVID periods, students did internships in various fields of work, followed a theoretical period consisting of a minor, or carried out practical research. They followed the lessons online, and meetings with fellow students and teachers, as well as conversations with respondents, took place via Teams.

The questionnaire related to personal stress, personal sources of energy and support, and their own coping strategies. Two group interviews were held with a number of respondents from the first study in order to properly interpret the results of the questionnaire. We were interested in their personal and professional development, what resources they used during the COVID period, and if these resources might have changed after 10 months of experience with COVID-19.

Results

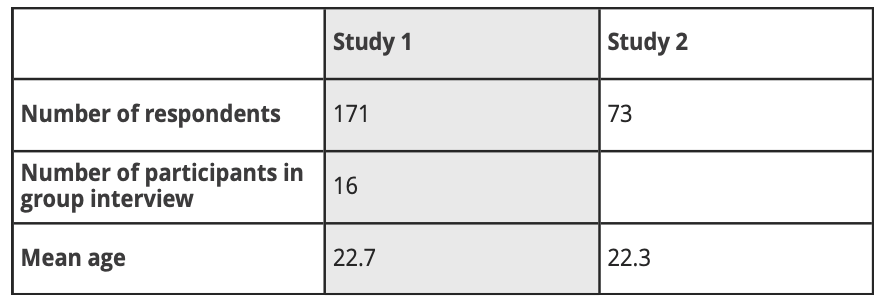

Both study 1 and study 2 involved third and fourth-year students. The third-year students from Study 1 and the fourth-year students from Study 2 were in the same cohort. The third-year students from Study 2 were new (see Table 1).

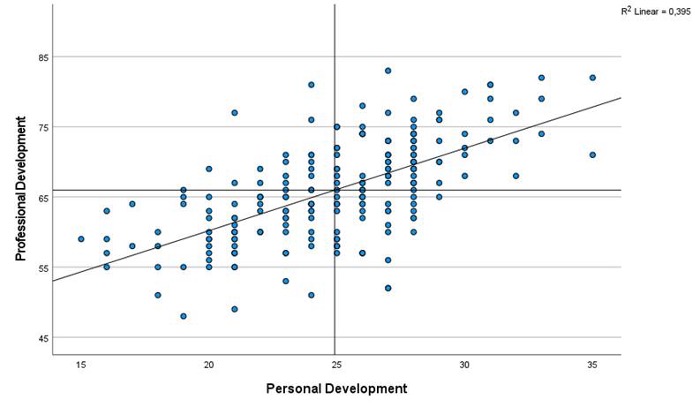

In both studies, we found a correlation between personal development and professional development: the higher the scores on personal development, the higher the scores on professional development. Although during the first study, students in the internship route scored higher than students in the theoretical route on professional development, this was reversed during the second measurement, so the differences in the total disappeared (see Table 2).

As the score of a respondent for personal development increases, so does the score for professional development. The ‘best fitting straight line’, based on the significant positive Pearson correlation, crosses the two average values of personal development (mean 25) and professional development (mean 66).’

During the first study, uncertainty about study progress was a major issue for all students. They initially lost control of the progress of their schoolwork. This had improved during the second measurement. During the internships, psychosocial stress occurred regularly because of higher work demands, thanks to COVID-19.

The three most frequently mentioned symptoms were fatigue (19.9%), uncertainty (18.6%), and worrying (14.3%). In the second study, students felt that the profession had become more meaningful (55.7% vs. 63.3%) and less risky (65.9% vs. 51.7%) for them.

Items that influenced imaging:

- ‘I think I have grown personally by experiencing this corona crisis’ (24% 1st measurement)

- ‘I have faster learned to use online tools, such as video calls (29.9%, 1st measurement)

Resources

Students could list the three resources most important to them. The results show that in both studies, students use personal coping strategies (dealing with problems, 24.6%), the preceptor (21.4%), and family and friends (21.4%) as important support. Also, they appointed their teachers for reflection lessons and peers as important during online meetings where they could discuss ethical dilemmas.

Conclusion and discussion

The question was whether bachelor nursing students were able to use sufficient energy sources during the COVID period to progress in their personal and professional development, which coping strategies they used, what their professional image looked like, and whether differences occurred between both coronavirus waves.

The results of both studies are largely comparable, which is an indication of the stability of the results. (3) Students have sufficient (personal) energy resources to make progress in their personal and professional development, even though they experience work pressure and uncertainty during their internship period. Support sources involved the student nurses using their own capabilities as well as seeking support from their social environment and the preceptor. Reflection meetings in school were also supportive. Exploitation of these resources forms a protective factor. (4)

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.