The Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil, this November (COP30) will celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Paris Agreement (COP21 in 2015), but where, Richard Beardsworth asks, do things stand ten years on?

The Paris Agreement: Failure?

A crowning achievement of the Paris Agreement was to make all 196 parties agree to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C”. In 2018, under scientific pressure to avoid dangerous climate thresholds, the goal was narrowed to 1.5°C.

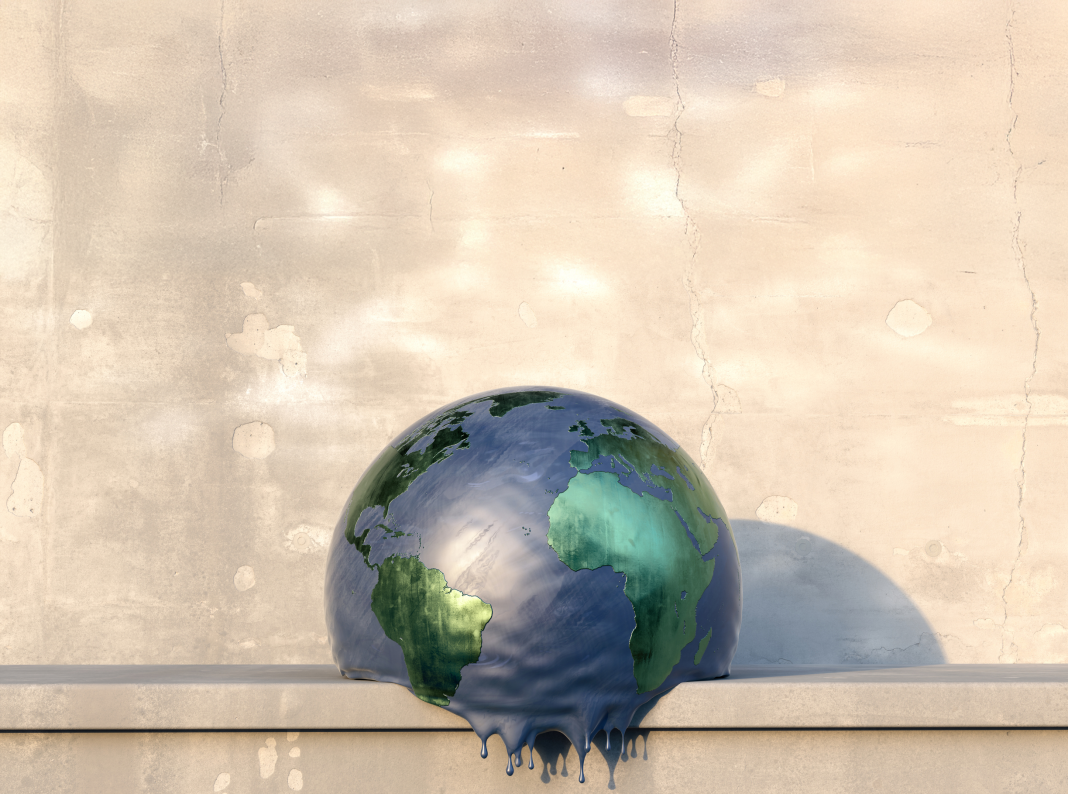

The world is presently on a trajectory of an average global temperature increase by the end of this century between 2.7°C and 3.1°C. The carbon budget aligned with the 1.5°C goal (the maximum amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted globally that keeps global warming at this temperature level) will be exhausted by the early 2030s.

The International Energy Agency has annually deferred the moment of peak oil (when oil production will reach its maximum and start declining) for the last five years, now saying that it will happen by 2030. This year, oil and gas majors cut back again on their investment in renewables in the name of profitability. Indeed, there is increasing analysis arguing that the world is embarked on an “energy addition”, not an energy transition (let alone a “just” energy transition).

The current U.S. administration has not only withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, leaving a hole in global climate leadership; it is now proactively making the “moral case” for fossil fuels to reduce poverty in the global south and energy prices in the global north. The last two conferences of the parties (COP28 and COP29, 2023-2024) were presided by hydrocarbon-rich states, and the outcomes from both meetings –

a “transition from fossil fuels” and the “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) of $300 billion per annum from developed countries by 2035 – disappointed many countries and civil societies.

Ten years after the Paris Agreement there is deep suspicion about the UNFCCC process. COPs appear as routine distractions from the catastrophic direction of the world, confirming at the ceremonious end of each year the failure of climate multilateralism.

The Paris Agreement: Renewal?

Given the above, is the tenth anniversary of the Paris Agreement, COP30 in Brazil, another collective waste of time? Undoubtedly not.

No other intergovernmental scenario brings together all the countries in the world to focus on climate mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. The world was on a path to an average global temperature increase of 4°C by the end of this century in 2015; in ten years, this increase has been brought down by over 1°C. Not only do we have no alternative to the COP process, but it is also clear that climate multilateralism has effects. As the incoming president of COP30, André Corrêa do Lago, has nevertheless said, COP30 must show that COPs have consequences to renew trust in their multilateral efforts, especially in the present geopolitical context.

What, then, can be achieved on the tenth anniversary of the Paris Agreement? There are four concerns that are immediately important if COP30 aims to reanimate the COP process.

First, while COP30 will not be a ‘climate finance’ COP, the climate finance package resulting from COP29 must remain central to the negotiations. There were two numbers at COP29. The first was the $300 billion to be put up by developed countries. The second was $1.3 trillion, which constitutes the investment goal, beyond the $300 billion, to be achieved by 2035 to help low- and middle-income countries transition to renewable energy and low-carbon economies.

Negotiations at COP29 indicated several avenues to find this money: MDBs leveraging their own capital with the private sector, the raising of international taxes on maritime transport, debt-for-finance swaps, the use of carbon markets and private capital. This package must remain centre stage since international climate finance propels global climate ambition around mitigation targets.

Second, throughout this year, on the road to COP30, countries will submit their new mitigation targets for the next ten years (Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs). COP30 will be the conclusion to these submissions. The world can only achieve something close to 1.5°C in the long term if all countries’ contributions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are implemented.

70% of present GHG emissions are emitted by upper-middle-income countries like China, Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico, as well as lower-middle-income countries like Egypt, India, and Iran. Except for China, they all require, to varying degrees, external investment to meet and increase their targets. Therefore, the ambitious mitigation strategies needed this year are inextricably linked with international finance. If COP30 aims to show that COPs have consequences, potential alignment between mitigation and finance must be visible.

Third, the UAE consensus of COP28 referred for the first time in the COP process to the major cause of global warming: fossil fuels. COP28 agreed to transition away from fossil fuels, to triple renewable energy and to double energy efficiency by 2030. Thanks to the manoeuvring of Saudi Arabia this energy package was not cited at COP29. Despite the international circumstances, and even though Brazil is itself pushing for oil exploitation in its equatorial region, this energy package needs to return to the table at COP30. If it is sidelined during negotiations, deep suspicion in the COP process will grow.

Fourth, Belém stands at the mouth of the Amazon. COP30 should be the COP of nature-based solutions (to mitigation and adaptation) and that of Indigenous communities, youth leadership, and future generations. The renewal of trust in COP action must be based on a realistic rehearsal of hope for the future.

These are considerable challenges in present circumstances. Brazil is seasoned in diplomacy, seeking international cooperation with all countries in the world. Ten years after the Paris Agreement, its COP30 must show a lot.