Dr Niamh Dooley and Professor Mary Cannon explore what young adult life looks like for individuals who had mental health problems as children

People who suffer with their mental health in childhood are at greater risk of poor mental health in adulthood. What is less well known is that they are also at greater risk of other poor outcomes such as substance misuse, physical health problems, loneliness, and unemployment.

In 2011, a classic study by Alissa Goodman and colleagues showed that poor childhood mental health was linked much more strongly to poor socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood than poor childhood physical health. (1) The past ten years of research broadly support those findings. (2-4)

Types of mental health problems in childhood

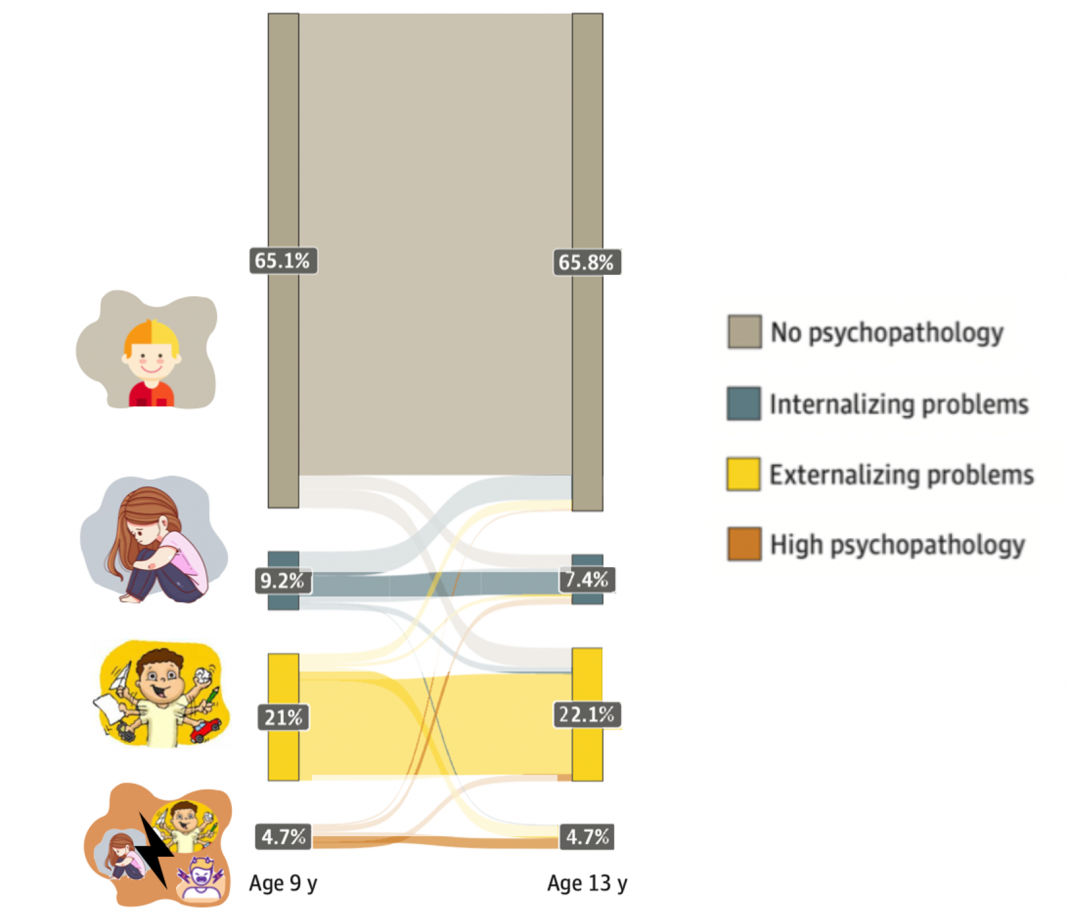

We recently examined this issue in over five thousand young people from the ‘Growing Up in Ireland’ cohort who were followed up from age 9 to 20. We divided the young people into groups depending on the level and type of mental health problems (also called psychopathology) that they reported on a questionnaire in childhood at ages 9 and 13. Using this approach, we, and others, have found that it is possible to categorise most children and adolescents into one of four groups depending on the type and severity of psychopathology. (5-7) (See Figure 1).

- No/low psychopathology (few problems – 65-72% of children)

- Internalising problems (depressive/anxiety/peer problems – 5-7% of children)

- Externalising problems (inattention/ hyperactivity/conduct problems – 20-22% of children)

- High persistent psychopathology (internalising and externalising – 3- 5% of children)

Poor outcomes in adulthood

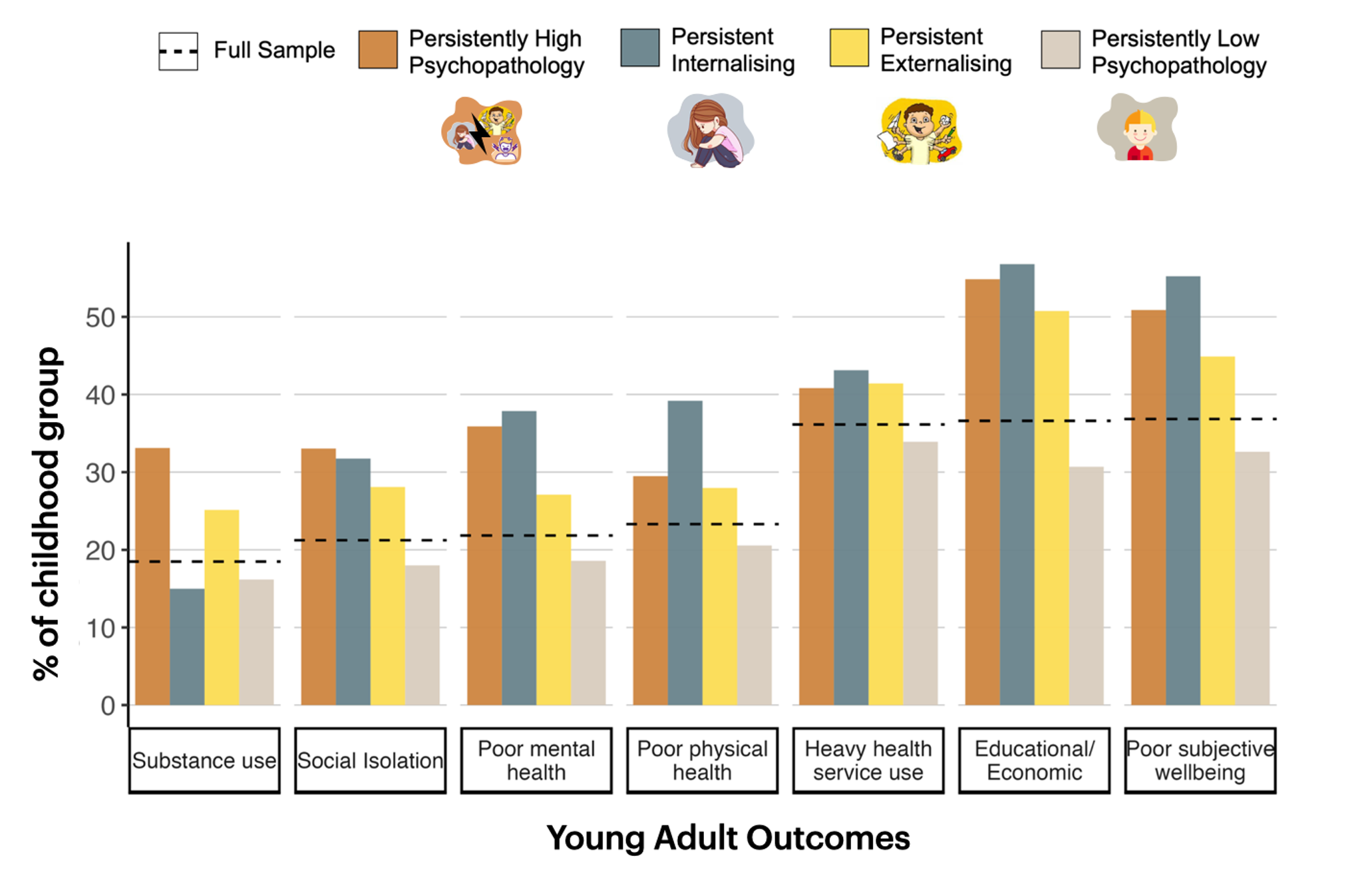

In our latest study, (8) we tracked these four groups into adulthood. Those young people who had moderate to high psychopathology of any type in childhood (i.e., groups two, three and four) had significantly poorer outcomes in their late teens and early 20s compared to those in the ‘No/low psychopathology’ group (see Figure 2). These outcomes included:

- Poor educational/economic outcomes (e.g., low grades, unemployment)

- Social isolation (e.g., few friends)

- Poor physical health

- Heavy substance use (e.g., alcohol, smoking)

- Heavy health service use (e.g., GP, emergency department)

Not all children

Not all children with mental health problems had the same risks of poor adult outcomes.

For instance, those in the internalising group were not at significant risk of becoming chronic smokers or heavy drinkers.

Females with childhood mental health problems were much more likely to develop physical health issues and to engage with health services as adults compared to males who had childhood mental health problems.

Hidden costs of childhood mental ill-health

What is clear from this research is that childhood mental health problems can have serious consequences for the individual (e.g., social isolation), their support network (e.g., financial difficulties), and society (e.g., social welfare payments, healthcare service use). Several studies have now shown that the cost of implementing screening and interventions to treat childhood mental health problems is considerably less than the long-term costs of not treating for the health sector and economy. (9,10)

Gen Z and the future

The ‘Growing Up in Ireland’ cohort we studied was born in 1998, and their childhood mental health was measured from 2007-2011. (8) But can we generalise our findings to today’s children? The international evidence suggests that childhood mental health has worsened over the past ten years. (11) This suggests we might see a much larger wave of mental health-linked adult problems for Gen Z and younger generations.

Calls to action

This research suggests that we may be able to minimise the long-term costs of childhood psychopathology to the individual and society by managing mental health symptoms in childhood in a timely and effective fashion.

For many countries, this may involve (1) Screening children and adolescents to identify those at risk; (2) Improving existing child and adolescent mental health services, especially at the community level; and (3) Diversifying the available supports, for instance, to include digital supports and expanding to other areas such as supporting the educational and future employment needs of children and adolescents.

In conclusion, our research shows that childhood mental health problems can have long-term effects on adult health and wellbeing. Better treatment of mental health issues in childhood and adolescence may prevent impairment in other areas, and we need a broader range of supports and interventions for children with mental health issues.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Health Research Board (Ireland)

References

- Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith JP. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(15):6032-7.

- Thompson EJ, Richards M, Ploubidis GB, Fonagy P, Patalay P. Changes in the adult consequences of adolescent mental ill-health: findings from the 1958 and 1970 British birth cohorts. Psychol Med. 2023;53(3):1074-1083.

- Chartier MJ, Bolton JM, Ekuma O, et al. Suicidal Risk and Adverse Social Outcomes in Adulthood Associated with Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67(7):512-523.

- Di Lorenzo R, Balducci J, Poppi C, et al. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: a systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021;33(6):283-298.

- McElroy E, Shevlin M, Murphy J. Internalizing and externalizing disorders in childhood and adolescence: A latent transition analysis using ALSPAC data. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2017;75:75-84.

- Healy C, Brannigan R, Dooley N, et al. Person-Centered Trajectories of Psychopathology From Early Childhood to Late Adolescence. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e229601.

- Basten MM, Althoff RR, Tiemeier H, et al. The dysregulation profile in young children: empirically defined classes in the Generation R study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):841-850. e2.

- Dooley N, Kennelly B, Arseneault L, et al. Functional Outcomes Among Young People With Trajectories of Persistent Childhood Psychopathology. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(9):e2336520.

- Shah JL, Moinfar Z, Anderson KK, et al. Return on investment from service transformation for young people experiencing mental health problems: Approach to economic evaluations in ACCESS Open Minds (Esprits ouverts), a multi-site pan-Canadian youth mental health project. Methods. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2023;14

- Ornoy A, Spivak A. Cost-effectiveness of optimal treatment of ADHD in Israel: a suggestion for national policy. Health Economics Review. 2019;9(1):24.

- Piao J, Huang Y, Han C, et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(11):1827-1845.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.