How can realist impact evaluation be used to upscale the integration of mental health programs for people of forced migration? Nancy Clark, an Associate Professor from the University of Victoria, investigates

Forced migration, displacement, and resettlement can be considered determinants of migrant mental health. Migrants are people who experience migration and/or forced displacement across or within national borders, e.g., refugees, asylum seekers, the undocumented, people who require temporary or permanent protection. (IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019).

It is estimated that by the end of 2022, 108.4 million people will be forcibly displaced (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR, 2023). Refugees (35.3 million) and asylum-seekers (5.4 million) make up 38% of the 108.4 million people forcibly displaced due to persecution, war, conflict, generalized violence, and human rights violations (UNHCR, 2023).

In both high- and low-income countries, nations have not adequately prepared for the large influx of migrants, which has stressed an already fragmented mental health system, resulting to least access to care, during and post migration. For people who experience forced migration due to violence and war, trauma may lead to mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, PTSD and psychosis. Approximately 1 in 5 people (20%) in settings affected by conflict have a mental health condition (WHO, 2022).

Migrant mental health inequities

Migrant mental health inequities are shaped by different social locations of people, e.g., their ‘race’/ethnicity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, migration status, and age – which intersect with structural determinants of mental health. Structural determinants of migrant mental health, as outlined by WHO (2022), include economic security, good quality infrastructure, equal access to services, quality of natural environment, social justice and integration, income and social protection, and social and gender equality.

Research highlights social institutions and policies (including those in healthcare) are also structural determinants that uphold intersecting systems of oppression, causing damage to the health of populations.

WHO mental health policies

The World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all (WHO, 2022) – lists several international frameworks for policy and practice to guide action on mental health, including the Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030; the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD); and forthcoming frameworks by WHO’s African Region, WHO’s Western Pacific Region and WHO’s Region for the Americas.

WHO (2022) argues most frameworks have lagged, creating further barriers to equitable mental health access to services and support for migrants. For example, in 2013, only 45% of countries reported having mental health policies and plans that were aligned with human rights instruments. Research shows that even in countries that have adopted explicit migrant health policies, such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, many migrants continue to receive inadequate access to mental health services and support, as well as barriers to care, including equitable access to universal healthcare coverage.

Evaluating migrant mental health

WHO (2022) advocates a policy shift toward integrated, community-based mental health care. Integrated mental healthcare is crucial for policy reform. Still, it requires a strong focus on local understandings, experiences, and solutions to scale up initiatives grounded in social justice, equity, and human rights. Integrated care involves multi-sector collaboration with primary healthcare services and those outside the purview of health, e.g., not-for-profit agencies, schools, and settlement organizations.

Global research agenda on health, migration and displacement (WHO, 2023), further highlights the need to improve the responsiveness of services to a diversity of migrant groups, e.g., language, religion, gender, and sexuality and the need to address structural determinants such as global immigration policies – the impact of restrictive immigration policies, securitization, and externalization of borders on the health of migrants, refugees and other displaced populations.

Scaling up migrant mental health requires a better evaluation of how social and structural inequities are reduced for migrant groups. To reduce health inequities for migrants, both individual-level and higher-order structural conditions must be analyzed concurrently to promote social justice and health equity at the point of care.

Realist impact evaluation offers a method for evaluating migrant mental health services because it allows stakeholders and researchers to understand in what context(s) it does integrated mental health care work? For whom does it work, and in what respects? Few frameworks have engaged with critical theoretical perspectives that aim to reduce inequities and oppression and promote social justice.

Intersectionality and realist impact evaluation

Social science theories such as intersectionality offer a critical approach to program evaluation. Originating in Critical Race and Black Feminist scholarship, intersectionality encourages critical reflection among decision-makers and policymakers to consider the simultaneous impact of identity (e.g., race, class, gender) and how power operates through systemic structures to create privilege and/or disadvantage.

Fitting with realist impact evaluation, intersectionality provides a social justice perspective by privileging local understandings, experiences, and solutions to create social change. In this way, intersectionality offers a multi-level analysis that goes beyond the health sector and brings migrant knowledge to the center of mental health programming and policy making.

Evaluating migrant mental health programs

Until recently, health systems have struggled to accommodate migrants, and rarely are they considered in health system planning Bulletin of the World Health Organization (nih.gov). There is a need to increase user and caregiver involvement to strengthen the mental health system and improve migrant mental health. Migrant groups are diverse and are exposed to various stress factors that affect their mental health and well-being pre-migration, during their migration journey, post-migration, and during their settlement and integration (WHO, 2022).

Evaluation of migrant mental health programs and practices needs to be considered within group differences while addressing overlapping and systemic inequities. For example, The Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030 commits countries to strengthen their surveillance systems for monitoring mental health, self- harm, and suicide; monitor disaggregate data by facility, sex, age, disability, method, and other relevant variables; and that they use these data to inform plans, budgets, and programs (WHO, 2022).

In this context, some nations have adopted a ‘gender-responsive’ approach to sex and gender disaggregated data to include income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability, geographic location, and other characteristics relevant to gendered experiences of migration (IOM UN Migration-Gender and Migration Data (2021). From an intersectionality perspective, gender is an intersecting component of wider structural inequalities. Gender should be considered in combination with other axis of social difference that shape migrant mental health.

Realist impact evaluation

Realist impact evaluation defines a program theory by identifying the contexts, mechanisms and outcome factors. Having a better understanding of what makes a difference is often hard to “see” and, therefore, requires identifying what mechanisms work for whom and how. For example, understanding of the CONTEXT – (interpersonal relationships, institutional settings, infrastructure), e.g., funding or staffing; the MECHANISMS – (program resources + responses), e.g., the reasoning of people and the OUTCOME – the result of people’s reasoning, e.g., increased access to primary healthcare – can transform community-based – mental healthcare and drive policymakers to act.

Scaling up mental health frameworks

Scaling up mental health frameworks can benefit from realist evaluation methods, which assume that certain contexts cause behavior change in people, e.g., (clinicians, patients, program managers, and policy actors). Therefore, there is an intentionality to include knowledge users’ (migrants and practitioners’) reasoning and reflexivity as part of the realist evaluation of mental health programs.

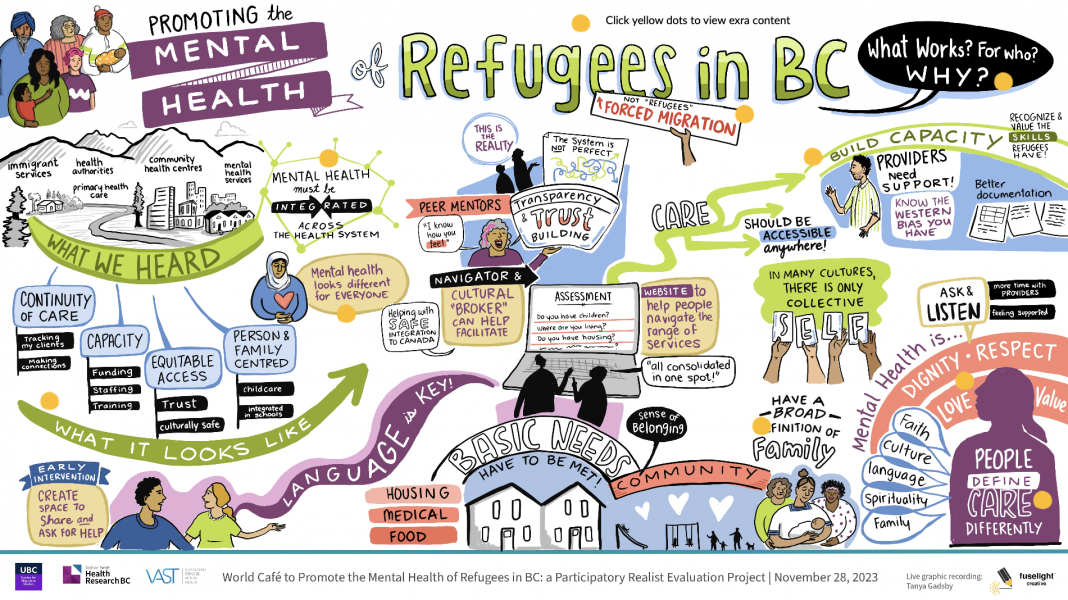

Over ten months, we engaged with 25 people across sectors and services (primary healthcare, settlement, mental health, and health authorities) as well as people with lived experience of forced migration in a regional context in western Canada through a series of online and in-person deliberative policy dialogues to find out about what contexts, programs/resources worked to promote migrant mental health.

A thematic analysis was done and resulted in 4 Key themes: Continuum of care, Capacity, Equitable Access, Person, and Family-Centered Care. These findings were then shared with the sectors and services to engage in an art-based multi-sector world café. The work will be used as a foundation for ongoing community engagement for a larger realist impact evaluation project to ‘test’ a working theory about what works to promote the integration of mental health services for refugees and other migrant groups. Preliminary findings suggest that the context of multi-sector relationships shapes care work and ‘caring’ as a key mechanism for the integration of mental health services and support for diverse migrant groups.

Transforming mental health programs

Better integration of mental health services and supports must include a global shift toward community-based care and require implementation and evaluation of how sectors work, what works well, and in what contexts.

WHO (2022) outlines a need to transform mental health by reshaping our environments, building stronger community networks and multidisciplinary engagement, and promoting person-centered, human rights-based care. However, upscaling transformative frameworks requires policies and practices that engage in critical social science methodologies and pragmatic evaluation methods. A realist impact evaluation framework informed by intersectionality holds the potential for system change to promote responsive, equitable migrant mental health.

References

- World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240049338

- Global research agenda on health, migration and displacement: strengthening research and translating research priorities into policy and practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO.

- Pottie, K.; Hui, C.; Rahman, P.; Ingleby, D.; Akl, E.A.; Russell, G.; Ling, L.; Wickramage, K.; Mosca, D.; Brindis, C.D. Building Responsive Health Systems to Help Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020144

- Ford-Gilboe, M. et al. How equity-oriented health care affects health: Key mechanisms and implications for primary health care practice and policy. Milbank Q 96, 635–671 (2018).

- Wankah, P. et al. Equity promoting integrated care: Definition and future development. Int J Integr Care 23, 6 (2023).

- Hankivsky, O. (Ed.). (2012). An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework. Vancouver, BC: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University. Retrieved from https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-014-0119-x

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.