Professor Erika Dyck, Canada Research Chair in the History of Health & Social Justice, discusses the extensive history and growing medical application of psychedelics known as the psychedelic renaissance

British psychiatrist Ben Sessa re-introduced the concept of the psychedelic renaissance in 2011, suggesting that it was perhaps time to rethink the role of psychedelic drugs in medicine. The idea has gained momentum, especially in places like the United States and Europe, where psychedelics had been part of psychiatric reforms in the middle of the twentieth century. However, the focus on the global north and western biomedicine does not capture the diversity of psychedelic history that has led to this moment.

The history of psychedelics

Psychedelics come in various forms, and the word itself is more connected to an idea, a state of mind, an aesthetic, or even an ontology, than to a precise description of a particular chemical structure or a family of drugs with shared pharmacologic properties. Psychedelics have been found all over the world, and archeological evidence suggests their existence stretches into ancient history. Given this vast expanse, our current psychedelic renaissance moment seems narrowly focused on resurrecting a small part of psychedelic history.

Looking beyond the Western biomedical context, psychedelics have fitted into different ways of thinking about the relationship between health and illness. We might consider Indigenous approaches that have cultivated and used psychedelics, or Sacred Plants more broadly, for spiritual guidance.

Some ceremonies, from Indigenous groups in the Amazon to practitioners of the Bwiti faith in Gabon, West Africa, consume psychedelic plants for key life-transition ceremonies – entering adolescence, preparing for taking on new roles in the community, or returning to the community after struggling with alcohol or other substances. Framed as spiritual more than psychological or medical, these ritualized applications have long roots and deep meanings for local participants.

Non-Indigenous subcultures have also embraced psychedelics as spiritual or creative catalysts. Psychedelic use that aims at spiritual, artistic discovery, or mere recreational fun does not seem to be an explicit part of the current psychedelic renaissance.

Yet, the association between psychedelics and enjoyment, even pleasure, looms large in this history. From writers and philosophers taking psychedelics to nurture intellectual insights to visual artists and musicians trying to move past tendencies and habits and engineers seeking psychedelic perspectives to generate technical innovations, these substances have a reputation for changing minds, not just treating pathological conditions.

Psychedelics and their associated stories have circulated the world through legal and illegal channels. In some contexts, they are inseparable from an entire ecosystem, cosmology, worldview, and fundamental way of interacting with the local flora and fauna.

Ayahuasca and peyote are examples of sacred plants with psychedelic properties whose powers are interpreted through local, mainly Indigenous, practices. In contrast, other psychedelics are characterized by their recent provenance and use as an escape from systems of thought or convention, maybe to turn away from the day-to-day realities and experience the world through a different lens.

Substances like 3,4-Methylenedioxy methamphetamine (MDMA or ecstasy), and 4-Bromo-2,5- dimethoxyphenethylamine (2CB), for instance, grew in popularity when enjoyed recreationally at raves and festivals where music and psychoactive drugs combined to produce a transformative effect that many consumers do not feel requires further interpretation.

Psychedelics as treatments for mental illnesses

The current psychedelic renaissance has largely focused on developing clinical perspectives that value psychedelics as treatments for mental illnesses, from PTSD to major depression and end-of-life anxiety. The list of potential candidates for treatment has grown exponentially in the past decade, reinforcing the idea that psychedelics have been overlooked as a pharmaceutical application.

The pharmacological history of psychedelics itself is not clear-cut. Swiss chemists, for example, invested in chemical research that indirectly resulted in the creation of lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD-25.

Introducing LSD to the world in 1943 attracted attention from beleaguered psychiatrists searching for alternatives to the increasingly moribund custodial-care approach for patients with mental illnesses. LSD, for a time, was swept up in a psychopharmacological revolution and found strong advocates in white-coated scientists who were very much part of mainstream Western knowledge networks and funding initiatives.

Psychedelics and American counterculture

By the mid-1960s, however, LSD was routinely associated with countercultural or anti-establishment views as its consumption extended far beyond psychiatric consulting rooms and clinics. This shift is emblazoned in recent American history with iconic individuals championing a psychedelic movement outside of a clinical context and as a value inherent to personal expression and freedom.

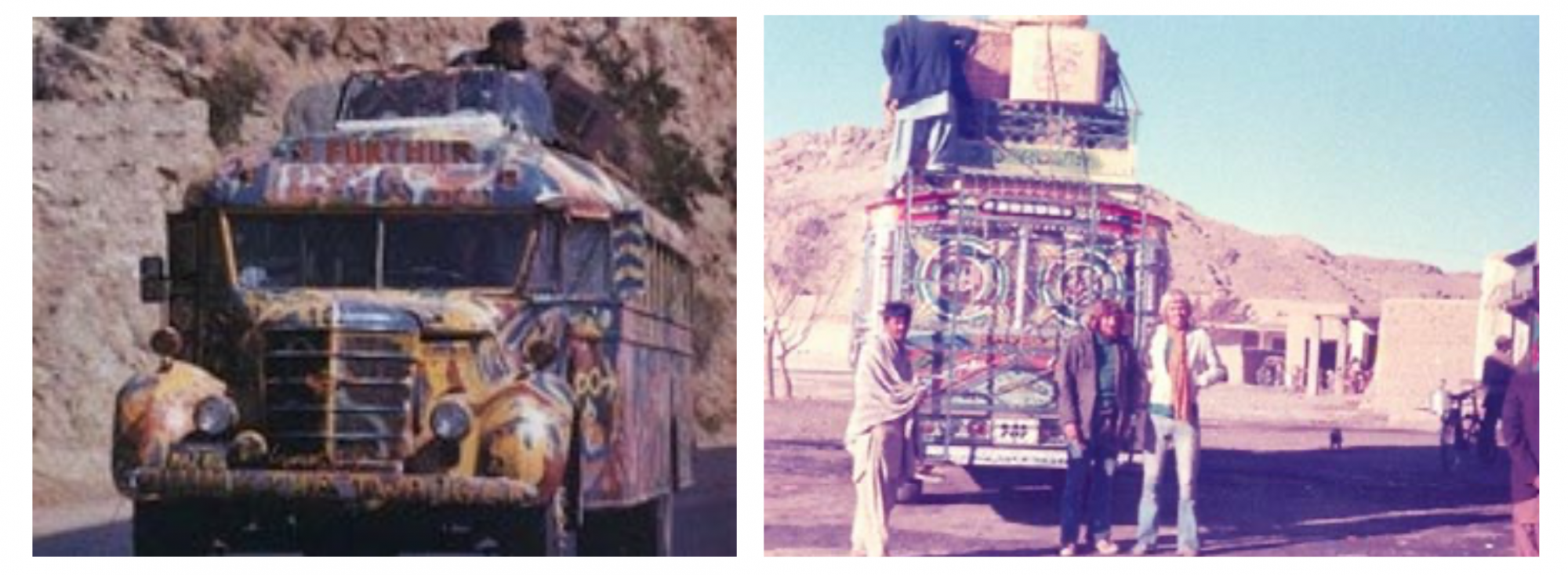

Whether it was Ken Kesey in a bus of Merry Pranksters mocking the American Dream in Day-Glo clothing, Tim Leary encouraging young people to stake out their paths independent of their parents’ expectations, or the Grateful Dead blending music with drugs to create new concert-going experiences, the explosion of psychedelics in the American context generated an association between these drugs and changing attitudes.

But America was not the only psychedelic counterculture, and the happenings of the Californian hippies sparked similar movements throughout the world.

Brazilian youths and artists also gravitated towards pharmaceutical psychedelics, despite a rich lineage of plant-based psychedelics in their midst. Generating their musical response and fomenting their political stances, psychedelics stimulated a powerful but hampered kind of political unrest in a country governed by a military dictatorship.

Meanwhile, Israeli youths completing mandatory military service sought psychedelics for a different kind of political activism. In the 1960s, young hippies, mainly from Europe and the Middle East, travelled cheaply along a route known as the “hippie trail,” seeking out novel perspectives and “exotic” encounters to help complicate their perspectives. Drugs were a part of this scene, but so was travel and experiencing non-western cultures, often culminating in festivals or gatherings in places like Goa, India, and Katmandu, Nepal.

The psychedelic renaissance and modern psychedelic medicalization

These non-medical applications of psychedelics have a rich history, yet their place in the current psychedelic renaissance is uncertain. Today’s focus on the medicalization of psychedelics may be an attempt to downplay these other historical threads or a first step towards recharacterizing the future of psychedelics as bona fide medicines.

But given hundreds, if not thousands, of years of evidence that psychedelic experiences have been used to address spiritual, philosophical, and cultural needs, it seems time to widen the scope of the renaissance to consider what non-medical and non-western practices are at stake at this moment, and what that means as we consider how to assess the benefits and risks of psychedelics in our modern world.

For more on the global history of psychedelics, click here.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.