Shai Gordin, Senior Lecturer at Digital Pasts Lab, Ariel University in Israel, enlightens us on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for studying ancient writing systems

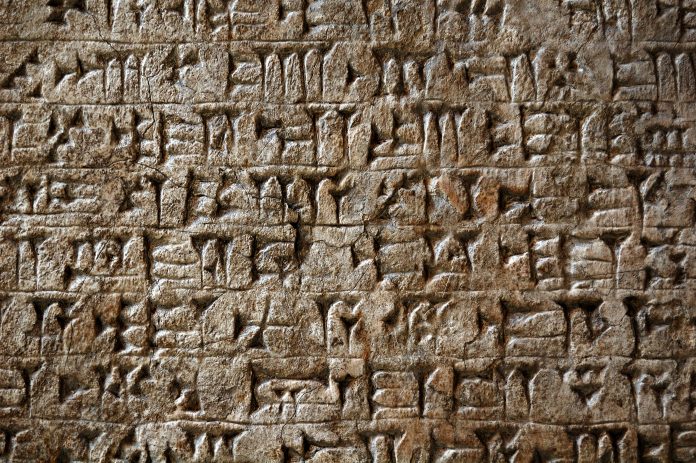

More than 5,000 years ago, in what is now Southern Iraq, someone decided to pick up a reed from the muddy banks of the marsh and use it to impress signs of writing onto a wet piece of clay. Over the next 3,000 years, cuneiform – as it would be dubbed by the Europeans who rediscovered the script in the 18th century – spread across the ancient Near East. More or less at the same time, Egyptian hieroglyphs blossomed into existence and were used for as long as cuneiform to write the ancient Egyptian language. Independently, writing developed in China, Mesoamerica and India, thousands of years later.

But possibly the greatest technological breakthrough in writing occurred in the Eastern Egyptian Desert and in the Sinai Peninsula, during the second millennium BCE. At this location and time, a group of individuals speaking a Semitic language started using Egyptian hieroglyphs as a purely alphabetic writing system. This writing system spread like wildfire in the societies of the ancient Near East in the first millennium BCE, and all ancient and modern alphabetic scripts used today are direct developments from it.

Writing is a revolutionary technology. It facilitates documentation at an unprecedented scale, encodes knowledge and meaning which are reflected in the mentalité of ancient societies. What, then, can we do with ancient knowledge of ages past? Hordes of documents, whether on clay tablets, papyri, ostraca and stone, stock museum shelves around the world. They exist already in millions – not including those still left to be discovered, waiting underground. Such immense treasures of cultural heritage should be democratised and disseminated to the general and scholarly public.

AI to make ancient texts accessible

How to achieve, nevertheless, this daunting task of making accessible such a large corpus of data? A possible answer is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to aid the process of digitisation and dissemination. Cuneiform texts, for example, are hardly ever made accessible for the general public. This complex logo-syllabic script, used for writing eight languages, presents such paleographical, orthographical and linguistic challenges, that intense scholarly work on each individual text makes it incomprehensible to laypeople. This also significantly slows down the speed of publication of these texts. AI, however, can provide an answer to some of these issues.

How close are we, for example, to the time when anyone can point their phone at a cuneiform tablet and hear a translation? This task, also known as machine translation, which we can now use daily in services such as Google Translate, has barely been attempted before for ancient languages. A project led by the Digital Pasts Lab has begun broaching such implementation for Akkadian, a Semitic language, the best-attested language in cuneiform sources. An application such as this can help break through many of the barriers that are usually faced by non-experts in the field when first approaching a cuneiform text. Of course, such translations are not perfect, and they are not close to replacing the expertise and comprehensive knowledge of the expert. Nevertheless, simple access to a text written thousands of years ago should not be barred from any individual so interested – while the reader is aware the translation is a single interpretation, offered by a machine.

But what does the machine need to produce a translation? In technical terms, this is the input we give the machine to receive the output of a translation. Currently, text recognition from images of cuneiform tablets is under development, but far from actualisation on a large scale. In the meantime, the best input for the task of translation is transliterations – transcriptions of cuneiform texts in the Latin alphabet.

There is, nevertheless, an in-between stage from visual identification to language comprehension. Approximately twenty years ago, Unicode characters for each cuneiform sign were created. These provide a visual representation only, since each cuneiform character is multivalent, meaning, it has more than one possible reading. Existing digitised textual editions can be used to train AI or a machine learning model, to identify the correct reading of Unicode signs. This creates one step of a pipeline: while working on the visual identification of cuneiform signs from images or 3D models, the next step of reading signs, extracting the linguistic meaning of the writing system, can already be successfully achieved using AI.

In other words, it is possible to achieve large-scale digitisation of cuneiform sources, which are inscribed upon hundreds of thousands of artefacts worldwide, using AI. We are not yet at the moment of this large-scale digitisation. Further development of additional machine learning models is needed to complete the pipeline described above, a pipeline that starts with an image of a tablet and ends with a translation to a modern language.

Closing remarks

The concepts presented here, specifically for the field of cuneiform studies, provide general insight into how such a process can effectively take place. It is important to remember how artificial these AI models can be. Unlike humans who instinctively do several tasks at once when reading a text, for the machine these tasks sometimes need to be broken down into their constituent parts.

Furthermore, the place of the expert vis-à-vis knowledge dissemination should not be disregarded when using AI. The knowledge that the machine accumulates is fundamentally different from that of the expert. While using AI to make accessible ancient texts, it is important to clarify their sources, and the manipulations the sources have gone through to make them accessible to the larger public. In other words, human intelligence is our most important resource to produce and understand AI.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.