Professor Giovanni Brandi and Dr Simona Tavolari, explore the link between asbestos exposure and cholangiocarcinoma malignancies

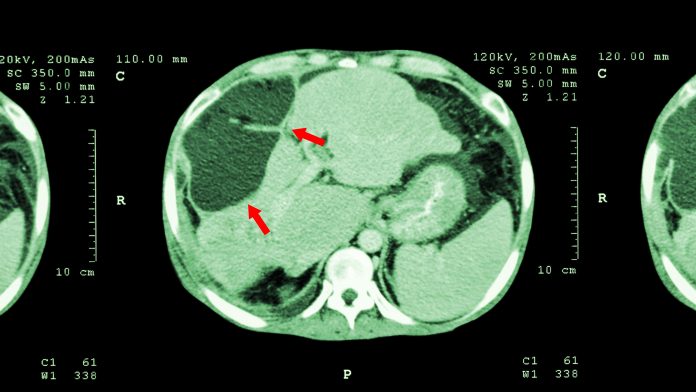

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a malignancy arising from the epithelium of the biliary tree and accounts for up to 25% of primary liver tumours. Anatomically, CCA is commonly divided into the intrahepatic form (iCCA), developing from smaller bile ducts located proximally to the right and left hepatic ducts within the liver, and the extrahepatic form (eCCA), developing from the right/left hepatic duct, cystic duct, or the choledochal duct outside the liver.

Albeit considered a rare malignancy in Europe and USA, the hospital charge associated with iCCA patients’ management has increased in the last 15 years in Western countries, whereas eCCA patients’ management has maintained stable or slightly decreasing. Of note, the registered global iCCA increment seems to have not reached a plateau and to represent a true phenomenon rather than the consequence of improved diagnostic techniques.

The broad geographic variations in iCCA incidence are thought to reflect a different distribution of the underlying risk factors. Currently, some pathological and genetic conditions (primary sclerosing cholangitis, hepatolithiasis, bile duct cysts, Caroli’s disease, liver fluke infections and hemochromatosis type 1) have been established as risk factors for this disease. In South Asian countries (Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam), where liver flukes are endemic, parasitic infections with Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini represent the major risk factors for iCCA development. A different scenario occurs in Western Countries, wherein up to 40% of diagnosed iCCAs the aetiology remains unknown.

To date, the role of occupational and environmental risk factors in iCCA development has been less investigated. An increased iCCA incidence has been reported among Japanese printing workers following chronic exposure to 1,2-dichloropropane and dichloromethane. However, as the global number of subjects exposed to these volatile organic solvents is limited, other environmental risk factors should be taken into consideration to explain the worldwide increased iCCA incidence.

Is there a link between asbestos exposure and iCCA?

Recent epidemiological studies have provided increasing evidence about a potential link between asbestos exposure and iCCA development. A case-control analysis based on the national occupational census data from 1960 to 1990 of 15 million people from Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden revealed a 70% increased iCCA risk for subjects with cumulative exposure to asbestos of ≥15.0 f/mL per year, compared to subjects never exposed. This evidence confirms and reinforces a previous retrospective Italian case-control study on 155 CCA patients matched up to four controls per case, reporting more than a fourfold increased risk of iCCA in workers exposed to asbestos compared to not-exposed.

The biological plausibility about the link between asbestos exposure and iCCA development has come from the detection of asbestos fibres in the bile/gallbladder of patients affected by benign diseases of the biliary tract and, more importantly, in the liver of iCCA patients living in Casale Monferrato, an area of Italy at a high level of environmental exposure to asbestos. Indeed, these findings provide clear evidence that asbestos fibres may reach other target organs beyond the respiratory tract, like the liver and the biliary tract.

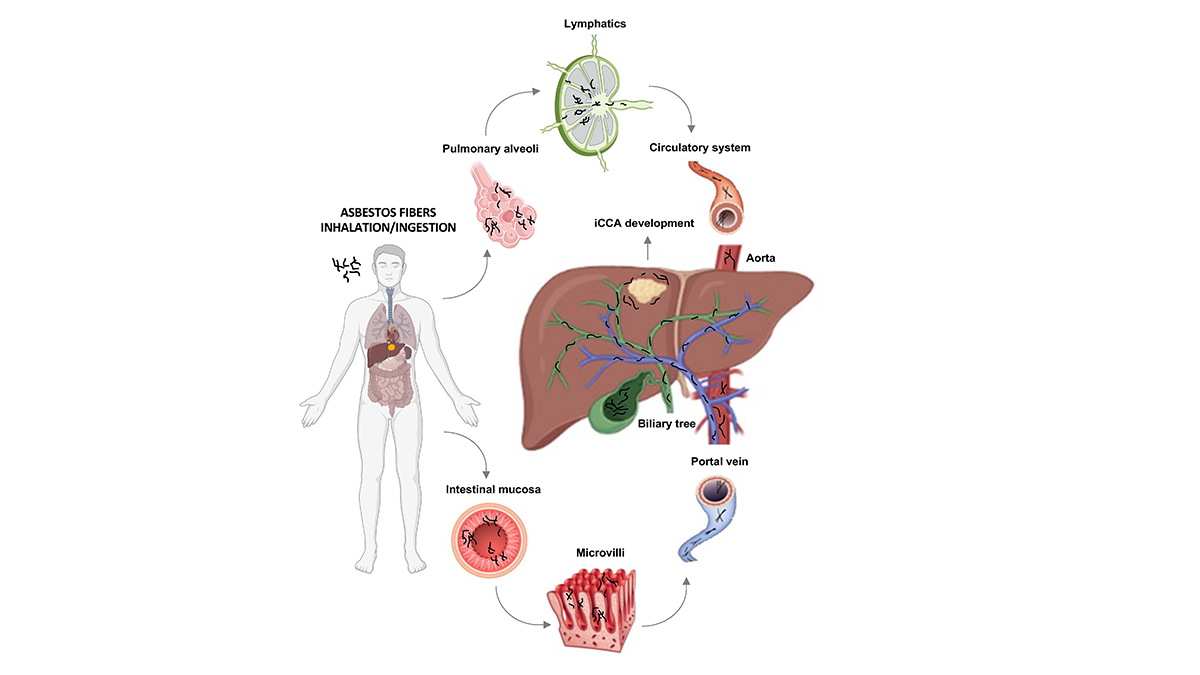

How do asbestos fibres enter the body?

Asbestos fibres can be introduced into the body by two main mechanisms: inhalation (the most involved) and ingestion (Figure 1). It can be hypothesized that, after crossing the alveolar barrier after inhalation or penetrating the gastrointestinal mucosa after ingestion, they may reach the circulatory system through lymphatic vessels and finally be delivered to all body districts. In the liver, thin and long asbestos fibres can be easily trapped in smaller bile ducts, thus explaining the strong association between asbestos exposure and iCCA development. Of note, as in the smaller bile ducts reside the liver stem niches with hepatic stem/progenitor cells giving rise to both hepatocyte and cholangiocyte lineages, it is conceivable that asbestos exposure may also lead to the development of mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocellular carcinoma, a rare primary liver cancer showing histopathological features of both iCCA and hepatocellular carcinoma and whose incidence has increased in the last years.

Currently, the knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying iCCA development is rapidly evolving, also due to the employment of new and powerful technologies such as next-generation sequencing. The use of these methodologies has already made it possible to identify a distinctive molecular signature in patients suffering from tumour diseases of environmental origin. Available molecular studies suggest that asbestos-induced carcinogenesis is the result of a complex interplay among different causative factors, including the time/dose of exposure and patient genetic determinants. Mutations of BRCA1 Associated Protein 1 (BAP1) gene, which is involved in environmental carcinogenesis, have been reported to occur with a high frequency in sporadic malignant pleural mesothelioma, a classic model of asbestos-related cancer.

Interestingly, a recurrent rate of BAP1 mutations has been also observed in iCCA patients exposed to asbestos compared to non-exposed, suggesting that this carcinogen may induce a typical molecular signature in target cells. Currently, 125 million people worldwide are still environmentally exposed to asbestos, even in countries that banned its use.

Recently, the role of asbestos exposure in the development of non-pulmonary malignancies, including iCCA, is gaining increased attention and consensus in the international scientific community and agencies. Overall, the body of evidence coming from epidemiological and mechanistic studies addresses a putative causal role of asbestos in the genesis of iCCA, deserving further investigations in large observational studies with accurate asbestos exposure assessment.

Asbestos fibres are introduced into the body by inhalation (the most involved) and ingestion. After inhalation asbestos fibres can reach pulmonary alveoli where they are drained by convective flows into pulmonary lymphatics. Once reached veins through the lymphatic system, asbestos fibres can potentially reach all organs via the circulatory system, including the liver. In the ingestion pathway, ingested asbestos fibres can cross the intestinal mucosa and be finally delivered to the liver through the portal vein. In the liver, asbestos fibres could remain trapped in the smaller bile ducts and exert their carcinogenic effect inducing cell malignant transformation.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.