A study, published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, finds that marine bacteria in the Canadian Arctic is capable of biodegrading fossil fuels – specifically, post-oil spill

Fossil fuels that spill into the ocean destroy ecosystems, animal biodiversity and cause huge clean-up timelines. Sometimes, oil spills are even used as weapons of war, as seen in the Gulf War in 1991. The oil spill was considered an act of environmental terrorism, as immense amounts of oil were released on purpose.

The oil seeped into local ecosystems, and was never truly cleaned.

But the biggest oil spill in history was the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, in 2010. The explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil killed 11 workers, spilling 60,000 barrels of oil into the Mexican Gulf every single day it remained uncontained.

Sean Murphy, who grew up in the region, begun the research project. Mr Murphy, an Aquatic Scientist, observed both the benefit offshore oil had brought to the people of Newfoundland and Labrador – but had been deeply troubled by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

When it comes to accidental oil spills, clean-up remains tricky and lengthy. In the amount of time it takes to solve the issue, the environment and local community can already be irretrievably damaged.

‘Providing nutrients’ can help marine bacteria work

A new study looks at the cleaning power of marine bacteria on the Labrador Coast, Canada. The Labrador Coast is crucial to Indigenous people, who depend on marine life for food security.

Co-author Dr Casey Hubert, Associate Professor of Geomicrobiology, University of Calgary, said: “The study also confirmed that providing nutrients can enhance hydrocarbon biodegradation under these low temperature conditions.

“These permanently cold waters are seeing increasing industrial activity related to maritime shipping and offshore oil and gas sector activities.”

Mini-oil spills in bottles to see how real ones work

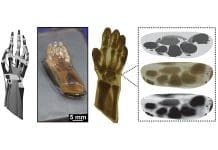

The study recreated oil spill remediations inside of bottles, by combining mud from the top few centimetres of seabed with artificial seawater. Then they added either diesel or crude oil, along with different nutrient amendments at different concentrations.

The experiments were performed at 4°C, to approximate the temperature in the Labrador Sea, which took place over several weeks. Dr Hubert further explained that these marine bacteria can be thought of as “nature’s first responders to an oil spill”. He further said:

“As climate change extends ice-free periods and increasing industrial activity takes place in the Arctic, it is important to understand the ways in which the Arctic marine microbiome will respond if there is an oil or fuel spill.”

The study also highlights that the region is so “vast and remote, such that oil spill emergency response would be complicated and slow.”