Neuroscientists have discovered the closest thing to the infamous “grandmother neuron” – they have identified the cells responsible for how the brain remembers faces

It’s not uncommon to hear the phrase “Sorry, I’m bad at faces” in the middle of a conversation, when someone is asked to reintroduce themselves. You can be introduced to someone, then meet again without any defining memory of who you’re talking to. On the opposite end of the spectrum, some people never forget a face – smoothly identifying the person they’ve seen just once.

But why? What makes some people remember?

Professor Winrich Freiwald, neurosciences and behaviour at The Rockefeller University, said: “The expectation is that we would have had this down by now. Far from it! We had no clear knowledge of where and how the brain processes familiar faces.”

A team at Rockefeller University have discovered, for the first time, what part of the human brain is responsible for recognising faces.

What is the grandmother neuron, and why is it a running joke?

Professor Freiwald explained: “When I was coming up in neuroscience, if you wanted to ridicule someone’s argument you would dismiss it as ‘just another grandmother neuron’–a hypothetical that could not exist.

In the 1960s, the idea of a grandmother neuron first emerged as a theoretical brain cell that would code for a specific, complex concept – all by itself. One neuron that could contain the memory of your grandmother, your mother, and everyone connected to them.

The proposal of a one-to-one ratio between brain cells and objects or concepts was an attempt to tackle the mystery of how the brain combines what we see, with our long-term memories.

Professor Freiwald further said: “Now, in an obscure and understudied corner of the brain, we have found the closest thing to a grandmother neuron: cells capable of linking face perception to memory.”

How did they find these cells?

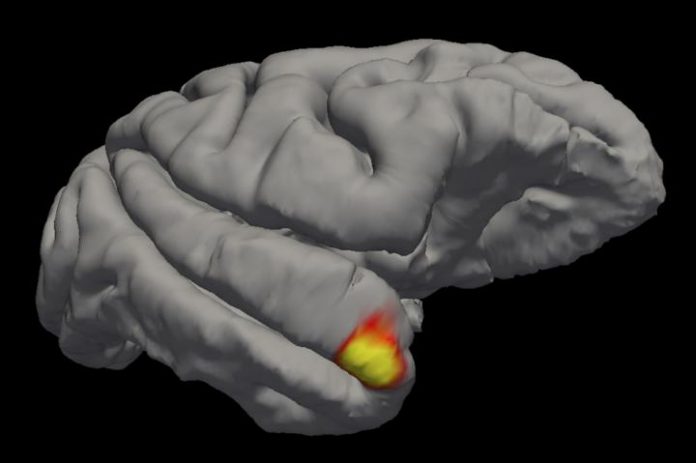

Freiwald and colleagues discovered that a small area in the brain’s temporal pole region may be involved in facial recognition.

So they used functional magnetic resonance imaging zoom in on the temporal pole regions of two rhesus monkeys. Then, they began recording the electrical signals of the temporal pole neurons as the monkeys watched images of familiar faces and unfamiliar faces that they had only seen on a screen.

The first evidence of a hybrid brain cell?

The team found that neurons in the temporal pole region responded to faces that the subjects had seen before more strongly than unfamiliar ones. And the neurons were fast–discriminating between known and unknown faces immediately after processing the image.

The team say this is the first evidence of a hybrid brain cell, similar to the fabled grandmother neuron.

The cells of the temporal pole region behave like sensory cells, with reliable and fast responses to visual stimuli. But they also act like memory cells which respond only to stimuli that the brain has seen before – meaning that familiar people change the brain.

“Face-blind people often suffer from depression. It can be debilitating, because in the worst cases they cannot even recognize close relatives,” said Professor Freiwald.

“This discovery could one day help us devise strategies to help them.”