Pete Mills, Commercial Technical Operations Manager at Bosch Thermotechnology Ltd, explains why CHPs are being left behind in the move to decarbonise industrial-sized heating

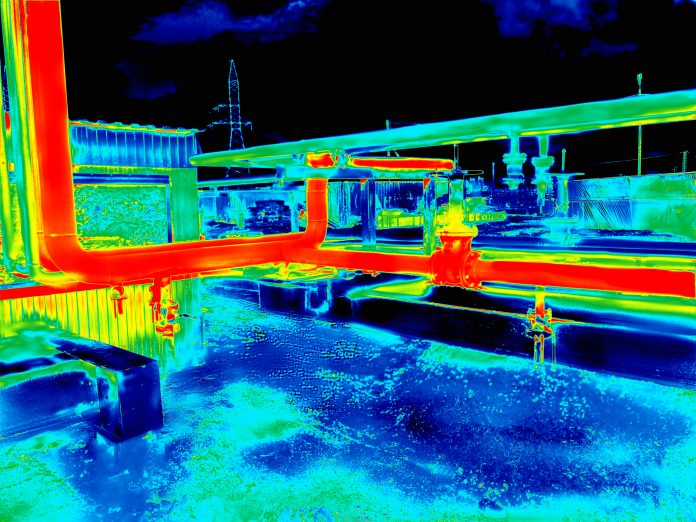

As we look towards decarbonising the way we heat our buildings, the importance of district heating will no doubt become more and more prominent. Its ability to power whole areas and multiple buildings can already help efficiency levels, however, its potential may be even greater in the future.

CHP (Combined Heat & Power modules)

Currently, CHP (Combined Heat & Power modules) has been the technology of choice for district heating plant rooms in the UK and have been for a while now. This is mainly thanks to their efficiency in capturing and using the heat which is produced when generating electricity. However, given our carbon targets, the technology is starting to struggle when using natural gas and is losing its potential as a future solution.

This is because the decarbonisation of the electricity grid has happened more effectively than we thought possible a few years ago, with lots of renewable energy coming onto it. This means that any CHP being installed now could be in a negative carbon situation in a few years.

With tougher regulations and more ambitious targets around carbon reduction, CHP may not easily find its place in the future heating technology mix. To name some examples, the latest Building Regulations look to significantly change the primary energy factors for electricity – this has already been adopted by the Greater London Authority. Given London has one of the highest uptakes of district heating schemes this is a tell-tale sign.

There have been investigations into what generating technology CHP would be offsetting and if it is enough to still have a future in district heating schemes. However, although we can’t be sure just yet, it is unlikely that BEIS will accept these arguments.

A strong replacement for CHP

So if CHP starts to filter out, what can take its place in the near future?

There is a temptation for heat pumps to be the sole heat source for a new heat network project. On the face of it, this looks like a simple option. Aligned with this there is an understandable desire from clients to do without a gas connection following the announcement from the UK Government that its intention is for no new fossil fuel gas use in new build domestic homes from 2025. This could lead to a significant uplift in capital costs for heat networks and concerns that it could cap the number of heat network projects being delivered.

Let us not forget plant replacement costs though, as heat networks typically will be designed to have a service life of the order of 40 years or more. It is important that a plant replacement strategy be thought about from the outset. The energy landscape may evolve significantly within the timescales of the plant, particularly if we are considering large-scale industrial equipment. One of the unique abilities of a heat network is its straightforward adaptation to multiple forms of heat that may become available in the mid-to-long-term.

One key energy transformation that is looking more and more likely is the decarbonisation of the gas grid to hydrogen blends and ultimately, 100% hydrogen. Without an existing gas supply, this option would be far more costly to implement later. If these can be utilised in heat networks, then the benefits will definitely put us in a good place as we continue our journey towards net zero. Particularly if a hybrid approach is applied.

A hybrid system would put a heat pump as the main source of heat, with support from peak load boilers. If hydrogen gas becomes a reality – and recent trials and Government interest seem to indicate it will – then a hybrid plant room can be easily adapted to run on the new fuel and achieve even greater carbon reduction benefits. In its report on hydrogen, the Committee on Climate Change makes a strong argument for hybrid systems, because of the flexibility this could offer in the future to shift loads off the electricity grid at times of peak demand.

A collaborative hybrid future?

Combined Heat and Power may have been the choice in the past, but a collaborative hybrid one could well be the future.