Bethany Torr, campaigns and advocacy officer at Leukaemia Care discusses the impact of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) on patients

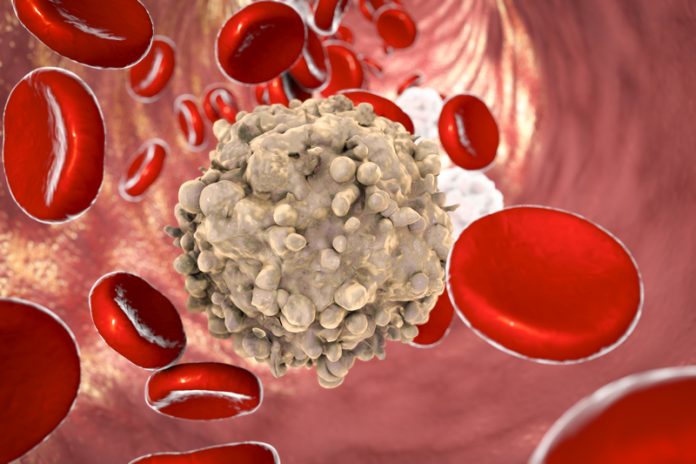

The perception of a leukaemia is often that it is a cancer that requires very quickly treating and is immediately life-threatening. This may be the case for acute (or quickly progressing) leukaemia. However, the most common leukaemia diagnosis in adults is chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), a slowly progressing and incurable blood cancer, that in two-thirds of patients does not immediately require treating at diagnosis. Instead, the patients will ‘watch and wait’.

Patients on ‘watch and wait’ will have regular blood tests and appointments to monitor the progression of their cancer. Treatment will not be started until the amount of CLL cells within the blood has increased to a point whereby healthy cells are significantly depleted, and this is causing problems. For many patients, this can take several years and for around 1 in 3, their CLL will never progress to a stage where it requires treatment.

This significantly differs from acute leukaemia, such as acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) that is the most common form of acute leukaemia in adults. In this instance, the number of leukaemia cells increases very quickly and if it is not diagnosed and treated promptly, there is a high risk for patients.

Traditionally, the treatment for both CLL and AML are chemotherapies. Chemotherapies are non-specific treatments. This means they are not targeted at cancer cells specifically and destroy healthy cells. This leads to significant side-effects and toxicities of treatment.

In AML, intensive treatment against the cancer is immediately necessary, but many patients are not fit enough to tolerate the treatment because 66% of patients are over the age of 65 years old. In contrast, unless CLL has progressed significantly, there is no immediate life-threatening reason to put patients through intensive chemotherapy. In fact, past practice demonstrated that treating patients early on leads to greater issues from chemotherapy toxicities than caused by the CLL. For this reason, ‘watch and wait’ was introduced.

During this time, CLL patients are often able to continue working if they are in employment and experience fewer effects on their finances, ability to walk and perform daily tasks compared to those who have been treated. In other words, patients on ‘watch and wait’ are living with their cancer.

This why a report published by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Blood Cancer in January this year was titled the ‘Hidden Cancer’. A patient living with a blood cancer could be anyone among us and for those on ‘watch and wait’ it isn’t necessarily obvious that they are doing so. In this sense, the cancer is ‘hidden’. However, just because CLL may not be visibly affecting someone, the diagnosis and living on ‘watch and wait’ often have significant effects on emotional well-being. Therefore, many people refer to the scheme as ‘watch and worry’.

In a recent survey, Leukaemia Care identified that more than half of patients (53%) living on ‘watch and wait’ felt more depressed or anxious since diagnosis, with 1 in 8 of these patients feeling constantly depressed or anxious.

Something that significantly contributes to this, is the lack of support and information provided for patients on ‘watch and wait’. Perhaps unsurprising when 3 in 5 patients aren’t offered any additional support, such as buddying or clinical nurse specialist access (identified to the be the most influential factor for a positive patient experience). Half of the patients aren’t given any guidance on finding further information and 68% aren’t given guidance on using the internet, such as signposting towards trusted websites.

Many patients describe feeling as though they are left to cope by themselves during the time between their follow-up appointments, particularly after the initial diagnosis. Patients are living with uncertainty, knowing they have an incurable blood cancer, but not knowing how long it will be until they require treatment. Indeed, if they will ever need treatment. It can be hard to come to terms with a diagnosis and without signposting to information and support, there can be many unanswered questions and concerns. This is not only difficult for the patient, but also for those around them such as family, friends and employers who all must adjust to the diagnosis.

Bethany Torr

Campaigns and advocacy officer

Leukaemia Care

Tel: +44 (0)1905 755 977