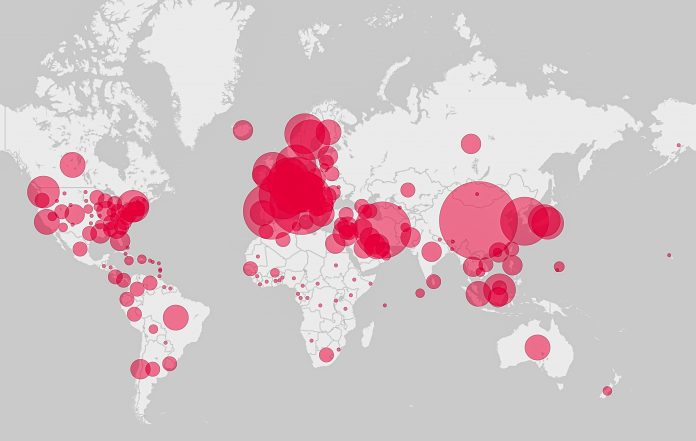

A new study combines genomics from COVID-19 samples with computer-simulated epidemics and travel records to reconstruct the virus’ spread across the world

Combining virus genomics with epidemiologic simulations and detailed travel records, the study reveals that in both the U.S. and in Europe, sustained transmission networks became established only after separate introductions of COVID-19 went undetected.

Early interventions were effective at stamping out coronavirus infections before they spread, according to the authors.

The results, which were published in Science, suggest an extended period of missed opportunity when intensive testing and contact tracing might have prevented SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, from becoming established in North America and Europe.

The paper also challenges suggestions that linked the earliest known cases of COVID-19 on each continent in January, to outbreaks detected weeks later. It provides valuable insights that could inform public health response and help with preventing future outbreaks of infectious diseases.

Michael Worobey, a University of Arizona researcher who led a team of scientists from 13 research institutions, said: “Our aspiration was to develop and apply powerful new technology to conduct a definitive analysis of how the pandemic unfolded in space and time, across the globe.

“Before, there were lots of possibilities floating around in a mish-mash of science, social media and an unprecedented number of preprint publications still awaiting peer review.”

The study analysed viral genomic sequencing efforts, which began immediately after COVID-19 was identified. These efforts quickly grew into a worldwide effort unprecedented in scale and pace and have yielded tens of thousands of genome sequences, publicly available in databases.

Contrary to widespread narratives, the first documented arrivals of infected individuals travelling from China to the U.S. and Europe did not snowball into continental outbreaks, the researchers found.

Instead, measures aimed at tracing and containing those initial incursions of the virus were successful and should serve as model responses directing future actions and policies by governments.

How COVID-19 reached the U.S. and Europe

The study identified a Chinese national flying into Seattle from Wuhan, China on 15 January was the first patient in the U.S. shown to be infected with the novel coronavirus and the first to have a SARS-CoV-2 genome sequenced. This patient was designated ‘WA1.’ It was not until six weeks later that several additional cases were detected in Washington state.

The team tested the prevailing hypothesis suggesting that patient WA1 had established a transmission cluster that went undetected for six weeks.

Although the genomes sampled in February and March share similarities with WA1, they are different enough that the idea of WA1 establishing the ensuing outbreak is very unlikely, they determined. The findings indicate that the jump from China to the U.S. likely occurred on or around 1 February instead.

The results also put to rest speculation that this outbreak, may have been initiated indirectly by dispersal of the virus from China to British Columbia, Canada, just north of Washington State, and then spread from Canada to the U.S.

Multiple SARS-CoV-2 genomes published by the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control appeared to be ancestral to the viral variants sampled in Washington State, strongly suggesting a Canadian origin of the U.S. epidemic. However, the present study revealed sequencing errors in those genomes, thus ruling out COVID-19 spreading in this way.

Instead, the new study suggests a direct-from-China source of the U.S. outbreak, around the time the U.S. administration implemented a travel ban for travellers from China in early February. The specific case responsible for the U.S. outbreak cannot be known for certain because tens of thousands of U.S. citizens travelled from China to the U.S. even after the ban took effect.

In Europe, on 20 January, an individual flew into Bavaria, Germany, for a business meeting from Shanghai, China, unknowingly carrying the virus, ultimately leading to infection of 16 co-workers.

In that case, too, an impressive response of rapid testing and isolation prevented the outbreak from spreading any further, the study concludes. Contrary to speculation, this German outbreak was not the source of the outbreak in Northern Italy that eventually spread widely across Europe and eventually to New York City and the rest of the U.S.

Early attempts to contain the virus

To reconstruct the pandemic’s unfolding, the scientists ran computer programs that carefully simulated the epidemiology and evolution of the virus.

“This allowed us to re-run the tape of how the epidemic unfolded, over and over again, and then check the scenarios that emerge in the simulations against the patterns we see in reality,” Worobey said.

“In the Washington case, we can ask, ‘What if that patient WA1 who arrived in the U.S. on January 15 really did start that outbreak?’ Well, if he did, and you re-run that epidemic over and over and over, and then sample infected patients from that epidemic and evolve the virus in that way, do you get a pattern that looks like what we see in reality? And the answer was no,” he said.

“If you seed that early Italian outbreak with the one in Germany, do you see the pattern that you get in the evolutionary data? And the answer, again, is no,” he said.

Co-author, Joel Wertheim of the University of California, added: “By re-running the introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into the U.S. and Europe through simulations, we showed that it was very unlikely that the first documented viral introductions into these locales led to productive transmission clusters,

“Molecular epidemiological analyses are incredibly powerful for revealing transmissions patterns of SARS-CoV-2.”

Other methods were then combined with the data from the virtual epidemics, yielding exceptionally detailed and quantitative results.

“Our research shows that when you do early intervention and detection well, it can have a massive impact, both on preventing pandemics and controlling them once they progress,” Worobey said. “While the epidemic eventually slipped through, there were early victories that show us the way forward: Comprehensive testing and case identification are powerful weapons.”