Researchers at Cambridge University found that over-activity in one brain region links depression, anxiety, and heart disease

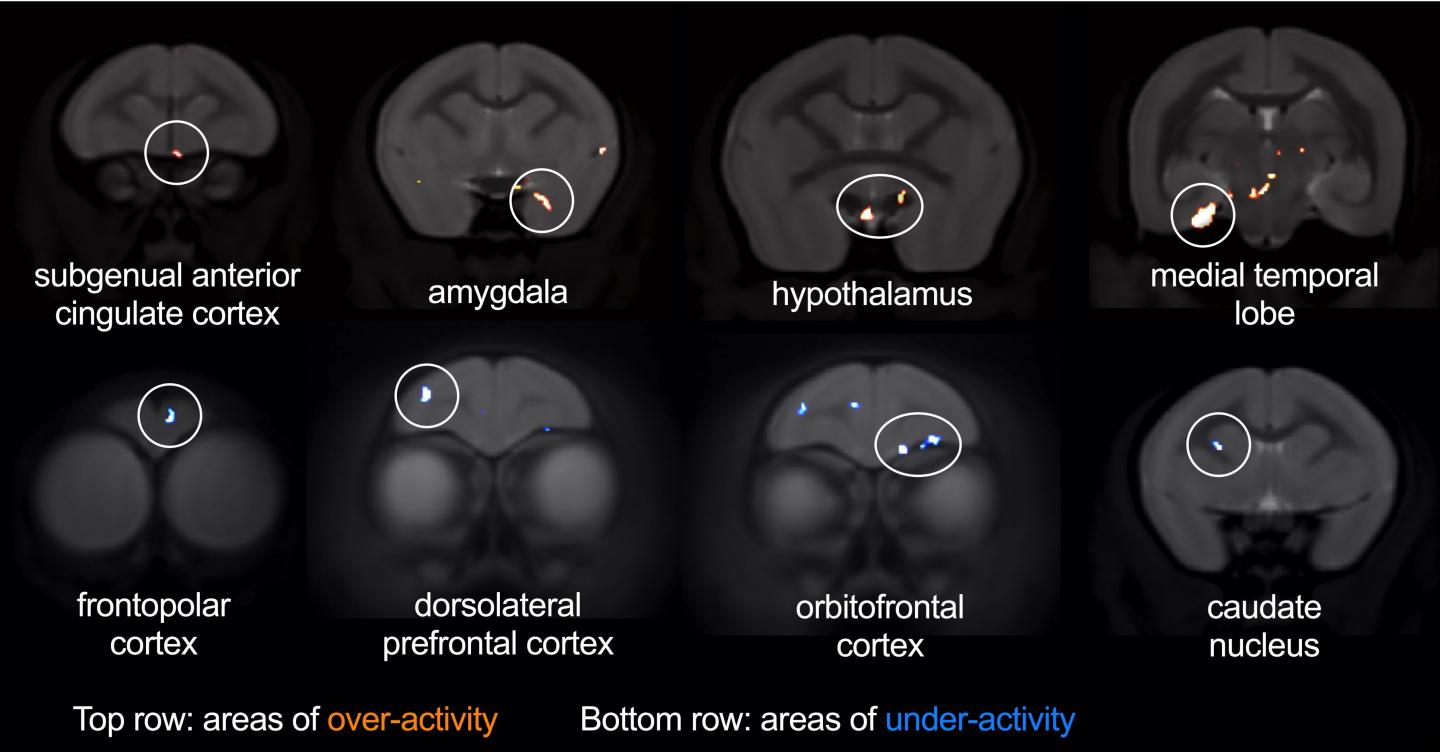

Research at the University of Cambridge has found that increased activity in a single key part of the emotional brain called the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) could underlie increased negative emotion, reduced pleasure and a higher risk of heart disease in depressed and anxious people. They further found that these symptoms react differently to antidepressants, despite being caused by the same change in brain activity.

“We found that over-activity in sgACC promotes the body’s ‘fight-or-flight’ rather than ‘rest-and-digest’ response, by activating the cardiovascular system and elevating threat responses,” said Dr Laith Alexander, one of the study’s first authors from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience.

A new study, published today (26 October) in the journal Nature Communications, suggests that sgACC is a crucial region in depression and anxiety, and targeted treatment based on a patient’s symptoms could lead to better outcomes.

The marmoset monkey experiments

The researchers found that sgACC over-activity increases heart rate, elevates cortisol levels and exaggerates animals’ responsiveness to threat, mirroring the stress-related symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Why use marmosets? The team found that these tiny primate brains share a lot in common with human ones, including the same brain region of sgACC. Into this region of the marmosets’ brains, the researchers infused tiny amounts of a drug to excite and over-activate.

Professor Angela Roberts in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, who led the study, commented: “The brain regions we identified as being affected during threat processing differed from those we’ve previously shown are affected during reward processing.

“This is key, because the distinct brain networks might explain the differential sensitivity of threat-related and reward-related symptoms to treatment.”

To explore threat and anxiety processing, the researchers trained marmosets to associate a sound with the presence of a rubber snake, an imminent threat which marmosets find innately stressful. Once marmosets learnt this, the researchers ‘extinguished’ the association by presenting the tone without the snake. They wanted to measure how quickly the marmosets could dampen down and ‘regulate’ their fear response.

Similarly, when the marmosets were confronted with a more uncertain threat in the form of an unfamiliar human, they seemed more anxious due to the over-activation of their sgACC.

Ketamine as the cure?

The researchers have previously shown that ketamine – which has rapidly acting antidepressant properties – can ameliorate anhedonia-like symptoms. But they found that it could not improve the elevated anxiety-like responses the marmosets displayed towards the human intruder following sgACC over-activation.

Professor Roberts commented: “We have definitive evidence for the differential sensitivity of different symptom clusters to treatment – on the one hand, anhedonia-like behaviour was reversed by ketamine; on the other, anxiety-like behaviours were not.”