Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive memory loss and cognitive impairments. Therapy development has been driven almost exclusively by the amyloid hypothesis, which poses that AD is caused by the amyloid plaques seen in postmortem brains of patients.

However, drugs targeting amyloid plaques have failed to show efficacy in clinical trials. A new approach is needed.

Our laboratory has recently demonstrated that the memory gene Arc controls the expression of most genes involved in the pathophysiology of AD. This finding sets the stage for a novel drug discovery trajectory to develop more effective AD therapies that potentially act in earlier stages of the disease. Targeting AD genes transcriptionally controlled by Arc opens a new frontier of “multi-target” therapy designed to intervene in several aspects of the disease simultaneously. Because Arc plays a critical role in regulating the expression of multiple genes and pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of AD, it could serve as a therapeutic hub for developing effective treatments.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is named after Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist who described unusual pathological features in the postmortem brain of a patient of his who suffered from severe memory loss, confusion, and unpredictable behavior. Alzheimer observed two distinct pathological features:

i) amyloid plaques, clumps of protein fragments, mainly beta-amyloid, that accumulate between nerve cells, and ii) neurofibrillary tangles, twisted fibers within nerve cells, primarily made up of a protein called tau. These findings marked the first identification of AD as a distinct form of dementia, separate from normal aging. Alzheimer reported his discovery in 1906, providing a foundation for understanding neurodegenerative diseases.

Amyloid plaques are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease and comprise a protein called beta-amyloid that builds up in the brain. They are a collection of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides, strings of amino acids that clump together and form insoluble plaques. They are mainly found in two brain regions, the amygdala and hippocampus, but can also be present throughout the cortex. Amyloid plaques can be detected in living people using amyloid PET scanning. In this procedure, amyloid plaques “light up” on a brain PET scan.

Since its discovery in 1906, the idea that amyloid plaques cause AD has dominated basic research and drug discovery efforts. However, several hundred clinical trials treating AD patients have failed to demonstrate efficacy. Ninety-eight unique compounds have been developed to inhibit the formation of plaques or remove existing ones. All proved ineffective at curtailing the disease. Therefore, these neuroanatomical features discovered in 1906 appear to be the proverbial red herring. Although both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles correlate strongly with the pathophysiology of AD, they may not be causative for the disease.

The strict focus on the amyloid hypothesis for developing AD therapies, at the exclusion of other potential mechanisms, is responsible for the current lack of adequate treatments. We need to change course and pursue new avenues. But first, we will review the mechanisms underlying learning and memory processes.

Memory: Learning, Storage, Consolidation, and Recall

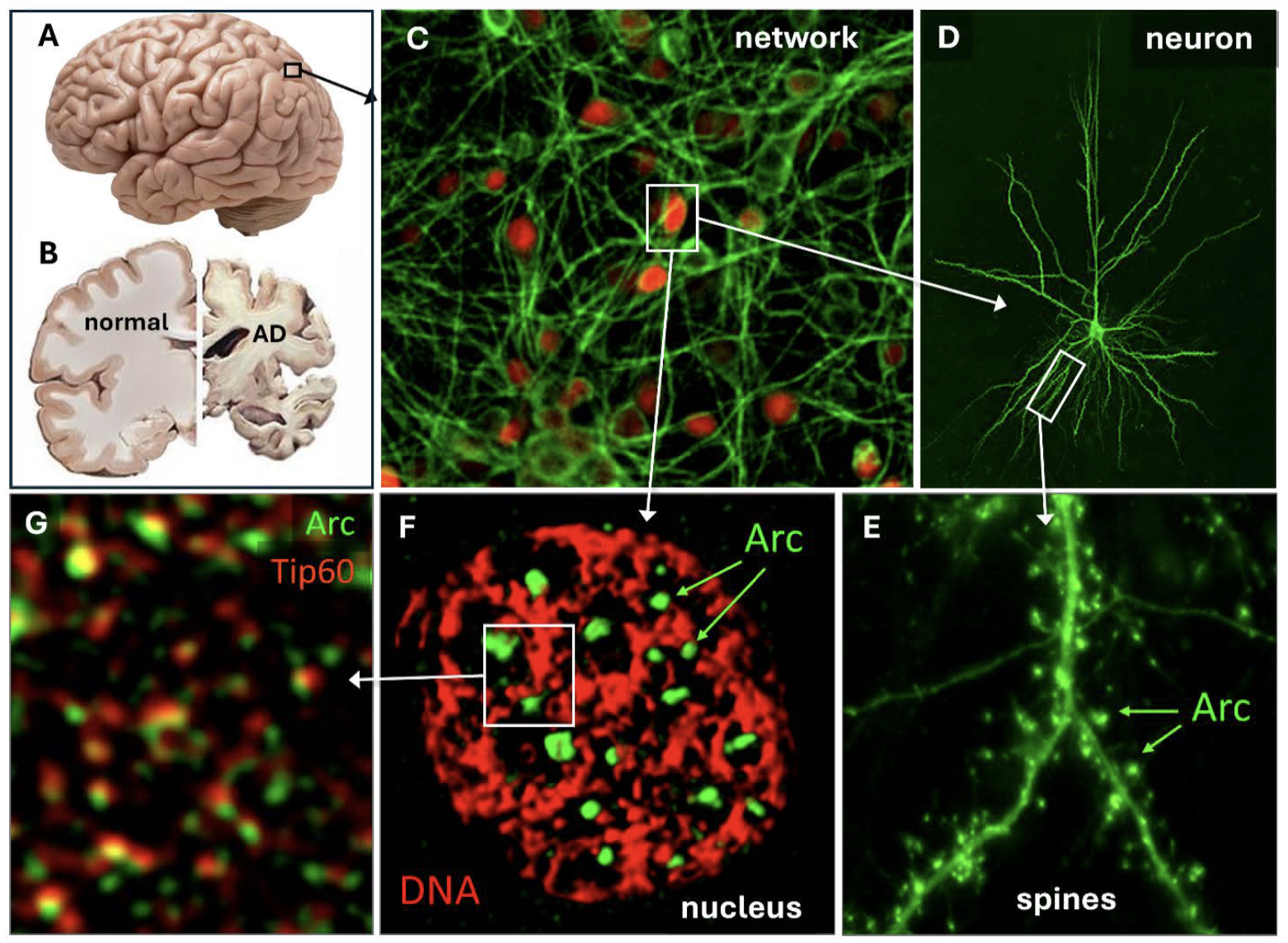

Memories are stored in the brain through a complex process involving several stages and brain structures (Fig. 1). Memory loss caused by Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with a significant loss of neurons and a decrease in brain volume (Fig. 1B). The human brain is the most complex organ in the body, comprising many regions with distinct functions. Each brain region consists of a network of neurons (Fig. 1C, D) densely interconnected through structures called synapses (Fig. 1E). Neurons in the human brain contain between a thousand and tens of thousands of synaptic connections. With an estimated 85 billion neurons in the adult human brain, the number of synapses ranges from 100 trillion to 1 quadrillion. Neurons and their synapses are thought to form the substrate for memory storage.

Synaptic connections allow neurons to talk to each other using a combination of electrical signals (spikes) and neurotransmitter signaling. As shown in Figure 1D, a typical neuron contains several neurites called dendrites, which are decorated by small protrusions called spines, where neuronal connections are made. Dendrites decode the incoming information from all the neurons that connect to it. In addition, a neuron has a single specialized neurite called the axon, which tends to be thinner and much longer than the dendrites. It branches out like a tree and connects with many neurons, locally in the same network or remotely in different brain areas. When a neuron is excited by synaptic inputs, it can fire an action potential or spike, a very short electrical pulse, that travels down the axon and causes neurotransmitter release at the presynaptic part of the synapse. There, it may excite the connected neuron, which could fire its own spike. The entire process only takes a few milliseconds. How much an axonal spike arriving at a synapse excites the next neuron depends on the strength of the connection, which depends on several properties, including the amount of transmitter released and the number of receptors it can bind to.

Each neuron integrates the activity of thousands of synaptic inputs, and when the excitation level is high enough, it fires an action potential. The result is a constant level of network activity in which neurons mutually excite each other. A class of inhibitory neurons is also present in the network to ensure the excitation doesn’t get out of hand.

So, how can the brain, with its billions of neurons making trillions of connections, “learn” something and memorize it?

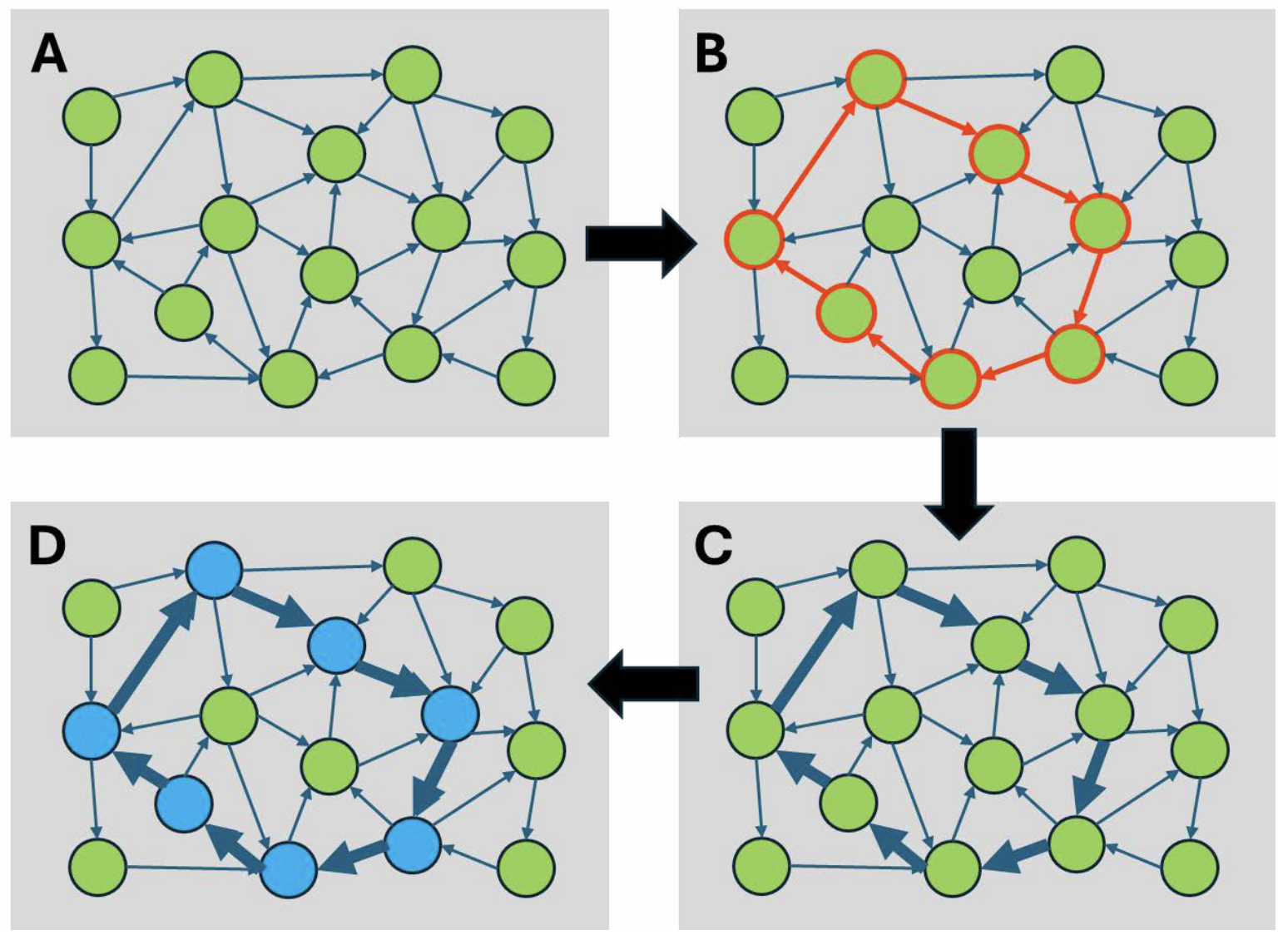

One important key is synaptic plasticity: the ability of synaptic connections to increase or decrease their strength or efficacy quickly in response to altered network activity (Fig. 2). This change in connectivity strength can last for a long time, thereby allowing information to be stored. Learning is the initial phase in which information is perceived and transformed into a format that can be stored. Sensory stimulation (auditory, visual, touch, smell, taste) elicits electrical activity in sensory neurons, which is transmitted to the central nervous system, where it activates a subset of highly interconnected excitatory neurons (Fig. 2B). Neuronal activity can reverberate for some time within this subset, thereby maintaining the sensory percept for a short time. When the neuronal activity is high enough, the synaptic connections between the neurons are strengthened by a process called long-term potentiation (LTP) (Fig. 2C). This results in a ‘memory’ lasting for hours to days. The increased connectivity between the neurons of this subset allows the original activity pattern (the percept) to be reliably recreated by a weak or partial stimulus: this allows the memory to be recalled from a cue or by association.

The strengthened synaptic connections are still relatively labile; they can be weakened by new synaptic activity. There is an additional process termed memory consolidation that ensures essential memories are stored for a prolonged period of time. When a connection strengthens after receiving strong synaptic inputs, it can signal the neuronal nucleus to change the structure of chromatin, protein assemblies that package genomic DNA (Fig. 1G). Chromatin remodeling plays a critical role in the formation of stable memories by regulating gene expression of plasticity and memory-related genes. Histones are proteins around which DNA is wound, and their chemical modifications influence chromatin structure. Key histone modifications include acetylation and methylation, which can loosen or tighten chromatin, thereby turning genes on or off. These epigenetic changes can persist for a long time, acting as a molecular memory that maintains the expression of essential genes involved in synaptic strength and plasticity. These persistent changes in gene expression in the subset of neurons that encode a memory to form an engram or memory trace (Fig. 2D).

The memory gene Arc is involved both in controlling synaptic plasticity and activity-induced chromatin remodeling. Therefore, Arc’s function in synaptic plasticity and the nucleus will be reviewed next.

The memory gene Arc

Arc (Activity-Regulated Cytoskeleton-Associated Protein) plays a critical role in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. It is an immediate early gene (IEG) that is rapidly expressed in response to synaptic activity, particularly in response to learning-related stimuli. Arc is a master regulator of synaptic strength, central to long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). In LTP, Arc contributes to the strengthening of synaptic connections by facilitating the trafficking of AMPA receptors to synaptic membranes, which increases the neuron’s responsiveness. AMPA receptors bind the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and mediate excitatory neurotransmission. Conversely, Arc is involved in receptor endocytosis, particularly the removal of AMPA receptors from the synaptic membrane. This downregulation of receptor density contributes to LTD, a mechanism critical for pruning unnecessary connections and fine- tuning neural circuits. Arc plays a critical role in homeostatic plasticity: it helps maintain overall neural circuit stability by participating in homeostatic scaling, which adjusts synaptic strength to stabilize neural network activity. For example, during periods of heightened activity, Arc can reduce synaptic strength to prevent overexcitation by promoting AMPA receptor internalization.

In the processes underlying learning and memory, Arc is indispensable for the formation and stabilization of memories. Memory encoding: Arc is rapidly transcribed in response to activity in learning-related tasks, indicating its role in encoding new information. Memory consolidation: Arc helps consolidate memories by facilitating synaptic remodeling and strengthening relevant neural circuits during post-learning. Mice in which the Arc gene has been knocked out only display short-term memory in a fear-conditioning test. Memory lasting more than a few hours is abolished in these mice. Spatial memory: studies show that animals with impaired Arc function exhibit deficits in spatial memory, suggesting its importance in hippocampus-dependent tasks. Synaptic tagging: Arc is critical in the synaptic tagging and capture hypothesis, which explains how transient synaptic activity leads to long- lasting changes. Arc acts as a molecular marker at active synapses, enabling them to “capture” plasticity-related proteins (PRPs) necessary for LTP and memory formation. Cytoskeletal dynamics: as its name suggests, Arc associates with the cytoskeleton and modulates structural changes at the synapse. Arc regulates actin filament organization in dendritic spines, the primary sites of excitatory synaptic input. This function supports the structural plasticity required for memory storage.

Arc protein is enriched in synaptic connections (Fig. 1E), where it acts as a master regulator of synaptic plasticity. However, it also localizes to the neuronal nucleus, where its function is only starting to be understood. Arc forms distinct puncta in the nucleus that associate with genomic DNA (Fig. 1F), and it colocalizes with Tip60 (Fig. 1G), a chromatin-modifying enzyme. Chromatin is a complex of DNA and histone proteins. Its primary function is to efficiently package the long DNA molecules into a compact structure, allowing them to fit within the nucleus. Histones help condense DNA and play a key role in regulating gene expression. Tip60 controls chromatin structure by acetylating histone lysine residues, which opens the chromatin structure, allowing access of the transcription apparatus for specific genes. Arc expression level correlates with the acetylation status of one of Tip60’s substrates, H4K12, a memory-associated histone mark that declines with age. Arc’s association with genomic DNA and chromatin is not random: it specifically colocalizes with regions containing histone marks for active transcription.

Malfunction of Arc expression or regulation is associated with neurological and psychiatric conditions, such as neurodevelopmental disorders: impaired Arc function is linked to autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and intellectual disability. Arc dysfunction also contributes to neurodegenerative diseases: abnormal Arc activity contributes to Alzheimer’s disease, which will be discussed next.

Arc and Alzheimer’s disease

Published studies have revealed a strong association between Arc and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A landmark study published in 2011 showed that Arc protein is required to form amyloid (Aβ) plaques. Moreover, Arc protein levels are aberrantly regulated in the hippocampus of AD patients and are locally upregulated around amyloid plaques. In contrast, a polymorphism in the Arc gene confers a decreased likelihood of developing AD. It has been shown that spatial memory impairment is associated with dysfunctional Arc expression in the hippocampus of an AD mouse model. These published results suggest that aberrant expression or dysfunction of Arc contributes to the pathophysiology of AD.

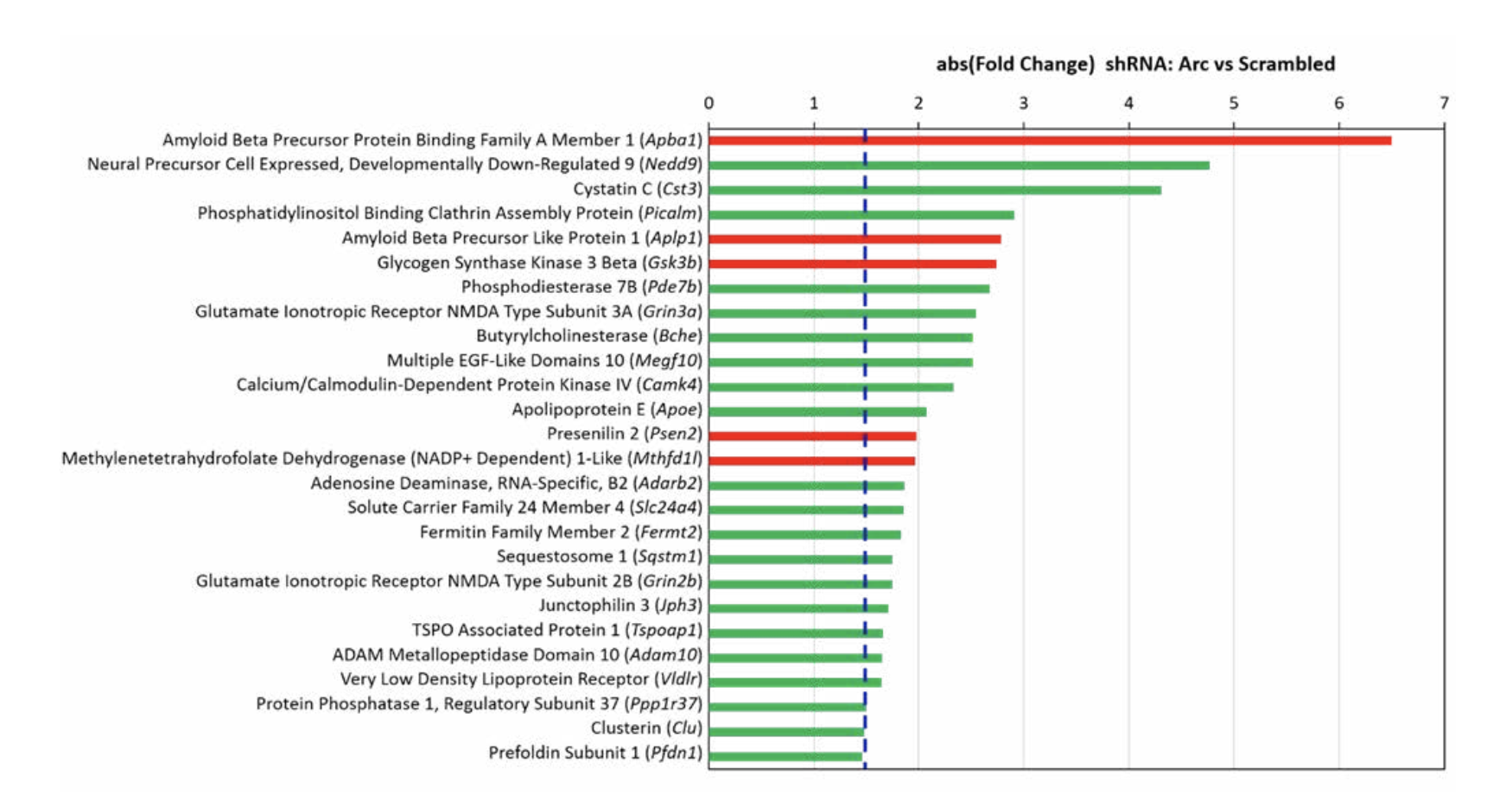

This idea has come into sharp focus with our recent finding that Arc is a master regulator of gene expression. When Arc expression was prevented in cultured hippocampal neurons using an RNA interference technique, the transcriptional program typically seen with network activation was dramatically altered. Notably, critical genetic risk factors of AD, including Picalm, ApoE, Slc24a4, and Clu were downregulated upon the knockdown of Arc. Out of 39 AD susceptibility genes, 26 were affected by Arc knockdown (Fig. 3). Arc also regulates genes that are more broadly involved in the pathophysiology of AD. While some differentially expressed genes control amyloid beta formation/accumulation through the regulation of cleavage and stabilization of amyloid precursor protein, others are involved in the hyperphosphorylation of tau and formation of neurofibrillary tangles. Arc knockdown also altered the gene expression associated with the neurodegeneration and neurotoxicity observed in AD. Finally, Arc-regulated genes are associated with altered cognitive function, an AD characteristic. In total, over 100 genes related to the pathophysiology of AD are transcriptionally controlled by Arc.

In summary, Arc is a master regulator of both synaptic plasticity and activity-dependent gene transcription. It exerts high-level control of two critical processes underlying learning and memory: alterations in synaptic strength following high-frequency inputs and changes in chromatin structure and transcription programs following network activation. Both are long-lasting, allowing the memories they encode to persist. Together, these two Arc-dependent processes allow for the formation of memory traces or engrams (Fig. 2). Arc has also been implicated in controlling the expression of many AD genes, suggesting that it could guide novel therapeutic approaches.

Arc as a therapeutic hub for Alzheimer’s disease

Existing pharmacologic treatments for AD, such as cholinesterase inhibitors and an NMDA receptor antagonist, only offer symptomatic relief. The failure of many high-profile clinical trials targeting beta- amyloid deposition or tau phosphorylation suggests that AD involves multiple pathways and complex interactions that still need to be fully understood. Innovative research avenues, like the role of Arc in AD proposed here, provide hope for new therapeutic strategies. Targeting Arc opens a new frontier of “multi-target” therapy designed to simultaneously intervene in several aspects of the disease. Because of Arc’s role in controlling the expression of multiple genes and pathways implicated in AD, it could serve as a therapeutic hub.

One could take at least two approaches to develop therapeutic AD strategies targeting Arc. The first one targets Arc itself, while the second approach targets the gene networks that Arc controls. Controlling activity-induced expression of Arc is possible because we have identified how neuronal activity-dependent transcription of Arc is regulated. It again involves chromatin modification, crucial in how our brain adapts and learns. Two specific types of changes to histones, the proteins that help package DNA, are methylation and acetylation. These changes can turn genes on or off, but how these changes are controlled in neurons is incompletely understood.

Our laboratory has identified two proteins that work together to modify chromatin and regulate the expression of the Arc gene. The key players are PHF8, a protein that removes certain chemical tags (demethylase), and Tip60, which adds acetyl groups (acetyltransferase). Note that Tip06 is also a binding partner of Arc, as discussed above. Interestingly, mutations in the PHF8 gene are linked to intellectual disabilities, and Tip60 has been connected to Alzheimer’s disease. This protein couple is quickly sent to the Arc gene’s regulatory region when neurons become activated. It removes a chemical mark (H3K9me2) that keeps the gene off and adds another mark (H3K9acS10P) that allows the gene to turn on. As a result, the Arc gene is activated and transcribed.

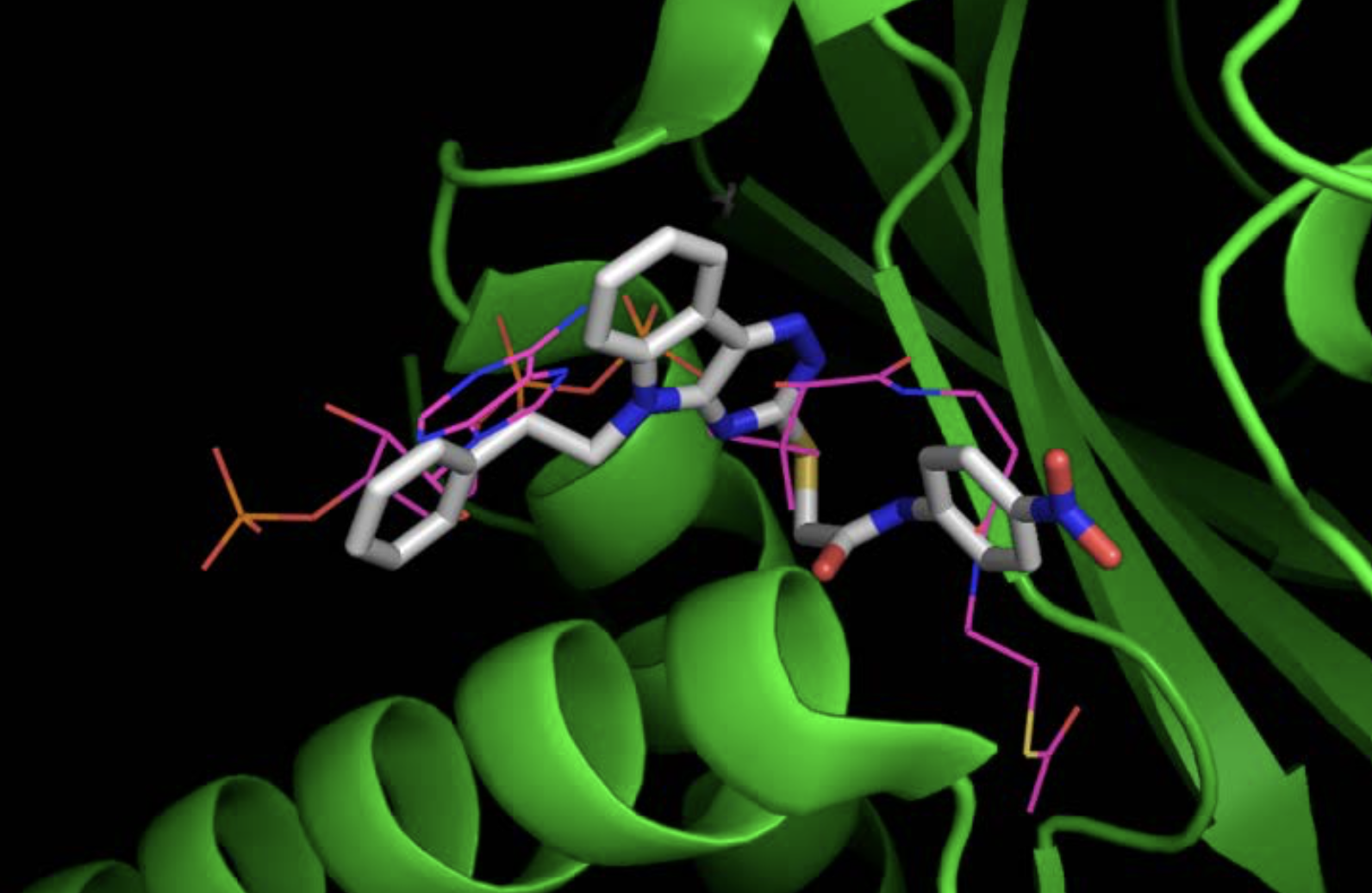

PHF8 and Tip60 are components of a chromatin-modifying complex that regulates the activity-dependent expression of Arc. High-resolution X-ray structures for both proteins have been published. We have therefore used an in silico screening procedure, the eHiTS docking algorithm, to identify drugs predicted to bind to Tip60 and PHF8 with high affinity. A library of 20 million compounds was docked into the acetyl-CoA binding site of Tip60 and the K4 and K9 binding sites of PHF8. Binding affinities were estimated for each compound and used to rank their estimated affinities. Several inhibitors for Tip60 and PHF8 were identified, which alter Arc gene expression individually and in combination. Figure 4 illustrates the optimal 3D pose of the top-ranking drug for Tip60. The efficacy of these novel drugs in preventing neuronal activity-induced Arc expression was demonstrated in cultured hippocampal neurons. These Tip60 and PHF8 drugs now need to be tested for their efficacy in reducing Arc expression and potentially slowing down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in a mouse model.

The pharmacological approach targeting Tip60 and PHF8 can only reduce Arc expression.

Given the preliminary data discussed above on Arc and Alzheimer’s, it is not yet possible to firmly conclude whether Arc function needs to be toned down or enhanced to be therapeutic in AD. A second approach to developing a therapy for AD involves targeting the genes and pathways that Arc transcriptionally controls. There are two classes: the expression of some genes is enhanced by Arc, while RNA levels for other genes are reduced (Figure 3). Therefore, we can mimic either inhibition or enhancement of Arc function by targeting the genes in one of these classes. If we inhibit the genes whose expression is reduced by Arc, we partially mimic the effect of Arc induction. If, on the other hand, we inhibit the genes whose expression is stimulated by Arc induction, we counteract the effect of Arc.

But how can we target the function of such a large number of genes? The answer is we exploit drug promiscuity, the ability of drugs to bind with high affinity to more than one target. A preliminary study using all FDA-approved drugs and 622 proteins co-crystalized with an FDA-approved drug demonstrated the feasibility of such an approach. We will need protein X-ray structures for members of the two classes of genes controlled by Arc. High- resolution structures are available for thirty proteins at this point. For the remaining genes without a protein X-ray structure, we can use alphafold 3 to predict the structures. Then, we can dock a very large database of 9 million compounds available for purchase into each protein structure and identify drugs that bind with high affinity to many class members but not to other proteins. Depending on which class was targeted, these promiscuous drugs will either mimic Arc’s function or counteract it.

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a debilitating disorder characterized by progressive memory loss and cognitive decline. Despite extensive efforts targeting amyloid plaques and tau tangles, these approaches have largely failed in clinical trials, highlighting the need for new strategies. Recent research suggests that the Arc gene, a master regulator of learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity, could offer a novel therapeutic avenue.

Arc plays a central role in synaptic plasticity by regulating synaptic strength and remodeling neural connections. It also controls the expression of many genes implicated in AD, including those associated with amyloid plaque formation, tau pathology, and neurodegeneration. Aberrant Arc expression has been linked to cognitive impairments in AD, making it a promising target for multi-faceted therapeutic approaches.

Therapeutic Potential: One approach would be to target Arc directly. Two proteins, PHF8 and Tip60, have been identified that regulate Arc expression via chromatin modifications. Drug candidates targeting these proteins have been identified and shown to influence Arc expression in neurons, with further testing needed in animal models of AD. A second approach targets Arc-Regulated Genes: Arc influences over 100 AD-related genes. Drugs could be developed to mimic or counteract Arc’s effects on these genes. A computational approach using protein structures and drug databases could identify compounds interacting with multiple target genes simultaneously.

By focusing on Arc, multiple pathways involved in AD could be addressed, offering a “hub” for innovative, multi-target therapies. This approach holds promise for intervening earlier in the disease and tackling its complex pathology more effectively than current single-target strategies.