Patients with diabetes mellitus in rural communities face major impediments in achieving and maintaining control of glucose levels and preventing complications; patients in these areas endure their healthcare being medically underserved and financially challenged

Patients in rural communities generally occupy the lower strata of income and educational attainment and often lack adequate transportation to their medical providers. Internet access is sparse, as is connectivity to telephone networks and to the technological components useful for diabetes management.

In the USA, the Federally Qualified Health Center system is a potential answer to providing both infrastructure and financial support for patients with diabetes in rural areas. A complementary solution to diabetes care in underserved, rural areas is to recruit retired endocrinologists using telemedicine to assist in patient management.

This treatise will review various factors which compromise the care of patients with diabetes living in rural, underserved areas. These involve geographical, financial, and educational factors as well as a lack of availability of endocrinologists, certified nurse educators and health insurance. A partial solution for these patients is to utilize Federally Qualified Health Centers (described below) and to convince retired endocrinologists to return to practice to help with patient management.

The goal of this article is to provide comprehensive information about the specific issues related to health care in rural, underserved areas; and specifically, to issues related to diabetes.

Demographic Factors regarding rural healthcare

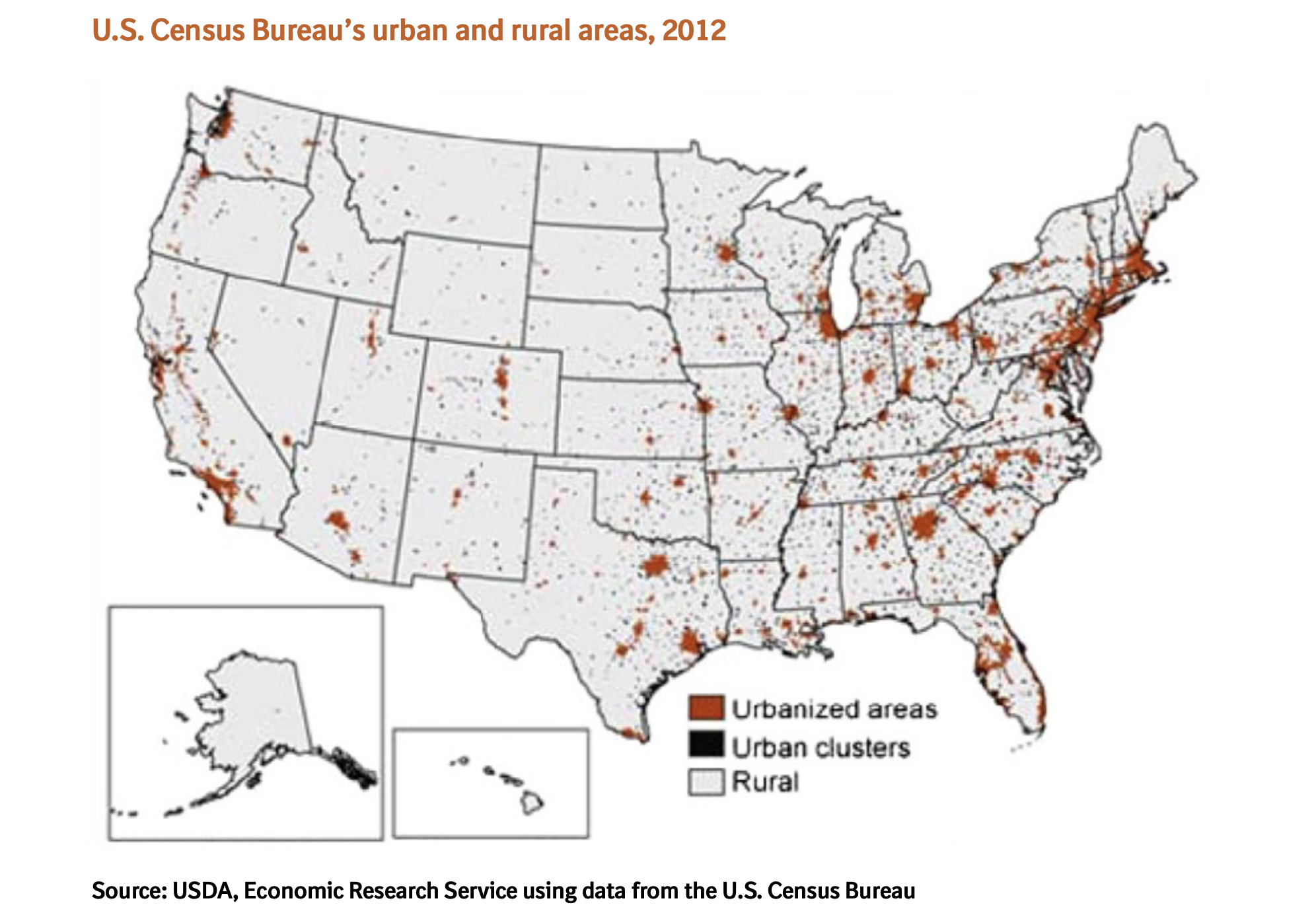

Nearly 25% of the US population lives in rural communities, compared with over 75% that reside in urban areas. (Figure 1).

Rural communities are unevenly distributed across the United States, with greater concentrations in the western and central regions of the country. Furthermore, a significant segment of the total rural population is aging, with an estimated 18% being over 65 years of age.

“Diabetes is increasing at an alarming rate worldwide and within the United States”

Populations within the United States disproportionately affected by diabetes are African-Americans, Hispanic-Latino Americans, American Indians, certain Asian American groups, and native Hawaiians.

Patients in rural communities experience a 17% higher prevalence rate of diabetes than their urban counterparts, with social indicators such as low educational attainment, financial constraints, and distance from providers contributing to the ongoing disparities.

The geographic maldistribution of physicians and other care providers adversely impacts rural populations. Only an estimated 10% of physicians practice in rural communities. One reason for this is that rural physicians and hospitals receive dramatically less federal government reimbursement payments than their urban counterparts for equivalent services.

These financial issues further complicate physician shortages in these areas as well as unwillingness to practice within the rural community settings.

Overview of impediments to optimal care in rural areas

General factors

These include lack of health insurance, barriers to healthcare access and education; long travel distances; lack of public transportation; communication difficulties due to lack of Internet coverage; and major financial challenges, including the ability to pay for prescriptions and professional fees.

The geographic maldistribution of physicians in rural areas limits the number of providers available for patient care. With sixteen per cent of the US population living in rural areas and only 10% of physicians practicing there, rural residents have been found to have a 17% higher rate of type 2 diabetes than their urban counterparts.

Health Insurance

The healthcare system in the United States is compartmentalized, with extensive coverage for some and minimal or no coverage for others.

Coverage for those over 65 is comprehensive due to the Medicare program, which provides health insurance for those over 65 and for individuals with disabilities. Another government plan, formally called the Affordable Care Act and informally Obamacare, provides insurance at a lower cost for otherwise uninsured patients.

Medicaid is a general term for individual state programs which provide coverage for individuals who cannot otherwise afford to pay for medical care. Current military service personnel and veterans who served in the military in the past are covered through the Veterans Administration system.

The CHIP program provides care for children living in families meeting financial requirements related to low income. Private insurance is available to those who can afford it. Even with all of these programs, there are approximately 15 million living in the United States who do not qualify or do not take advantage of these programs and consequently have no health insurance.

Notably, patients living in rural areas are more likely to be uninsured (17.8%) than their urban counterparts (15.3%).

Internet access

In general, federally funded clinics in rural areas are confronted with poor broadband coverage, as are many rural healthcare providers. Although the federal government is trying to provide grants to improve broadband coverage, this still is not adequate in rural underserved areas.

When the author became involved with these clinics in Southwest Virginia, he sought to identify specific internet limitations experienced by patients living in underserved areas. He initially documented this by accessing the signal strength bars from Verizon and T-Mobile, 2 major Internet services, when driving through the areas of referral. Many areas had no signal at all, and other areas had signal when at the top of hills or in non-mountainous areas.

This deficiency markedly diminishes the ability of physicians to utilize technology to access continuous glucose monitoring data and also supervision of the use of insulin pumps, as glucose data is not readily accessible online by the provider. Numerous technology options are necessary to care for patients in rural areas, but a lack of cell phones, transmission towers, and cell phone connectivity hinders utilization.

Lack of Specialists

Rural underserved areas in the United States lack specialists to take care of chronic, longstanding medical problems. This is particularly true for endocrinologists. Workforce data from the United States indicates a large gap in the number of endocrinologists available to take care of patients with uncontrolled diabetes. According to the work of the Vigesky and colleagues, there were only 5496 board-certified adult endocrinologists in the United States in 2014, and this has not improved substantially.

Diabetes affects 27 million in the United States, and the prevalence is increasing, particularly due to the increase in obesity. In the United States, only 15% of patients with diabetes at the present time are evaluated by endocrinologists. To meet this need, each endocrinologist would have to evaluate 5500 patients with type 2 diabetes.

The American Diabetes Association recommends a referral to an endocrinologist and a diabetes educator when patients do not achieve the desired goals of treatment, namely a hemoglobin A1C of ≤ 7%. In a 1602 type-2 diabetes patient trial, the average A1C at the end of the intervention was 9.0±1.8%, with very few patients less than 7%. This data suggests that a large fraction of patients with type 2 diabetes should be referred to an endocrinologist for advice or management.

Health disparities

A major reason we see health disparities for patients with diabetes in rural areas is that rural populations tend to encompass a large proportion of ethnically diverse cultures, including non-Latino whites, Latinos, African Americans and Native Americans. This diversity accompanies the use of complementary and alternative medicine options that include herbal and dietary remedies and spiritual interventions. These alternative approaches to health care are often integrated with Western-based medical care.

These patients are less likely to commit to routine glucose monitoring and exercise. Factors associated with an increased risk of unsuccessful diabetes self-management include a lack of self-confidence which hinders the ability to follow recommended guidelines; unavailable social support during the teaching of type 2 diabetes self-management skills; and a negative outcome expectancy for self-management.

Financial considerations

The costs associated with diabetes care also provide a substantial obstacle for patients in rural communities. These residents tend to be poor and are more likely to live below the poverty level than those living in urban areas. These residents are more likely to rely heavily on federally funded programs for food stamps and health insurance. In addition, rural residents are more likely to be uninsured (17.8%) than their urban counterparts (15.3%).

It is not surprising that limited financial resources often constrain the active participation of patients in rigorous clinical treatment regimens. Additionally, patients in rural communities are more likely to defer care because of treatment costs compared to their urban counterparts.

Moreover, access to safe sidewalks, walking tracks, exercise facilities, and grocery stores with affordable produce is sparse within rural areas, further impeding the potential for successful self-management.

Low educational attainment represents another problem

The National Standards for Education Statistics 2007 reported that high school graduates within rural communities are less likely to enroll in college than graduates in any other locale, with an even smaller percentage of rural adults obtaining a bachelor’s degree.

Low education levels often inhibit a person’s ability to understand and manage a disease as complex as type 2 diabetes. Compounding this are communication barriers such as language, hearing, or visual impairment, as these limit a person’s ability to fully comprehend or have the agency to successfully self-manage their disease.

The aging population in rural communities exacerbates these issues even more, as this group often experiences visual changes, dexterity, cognition, and mobility that hinder efforts at successful self-management of diabetes.

Other roadblocks to care for patients in rural communities

The diverse geography of rural communities multiplies the challenges in obtaining health care. Rural residents often encounter increased travel distances, extreme weather conditions, environmental climate barriers, and challenging roadways. Depending on location, rural residents must deal with mountainous regions, desert regions, and or traversing rivers and other large bodies of water. These topographical issues create added obstacles for persons already living on the margins, with fuel prices, lack of public transport, or limited vehicle transportation all impacting their ability to reach their nearest healthcare professional.

In terms of a communities’ ability to provide adequate health care, an aging population creates an increased burden and augments the need for more support programs for the elderly. The development of effective community-based strategies for promoting adequate health care is reliant upon a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence the behaviors and activities of rural-dwelling adults with diabetes.

The Federal Government program for underserved areas

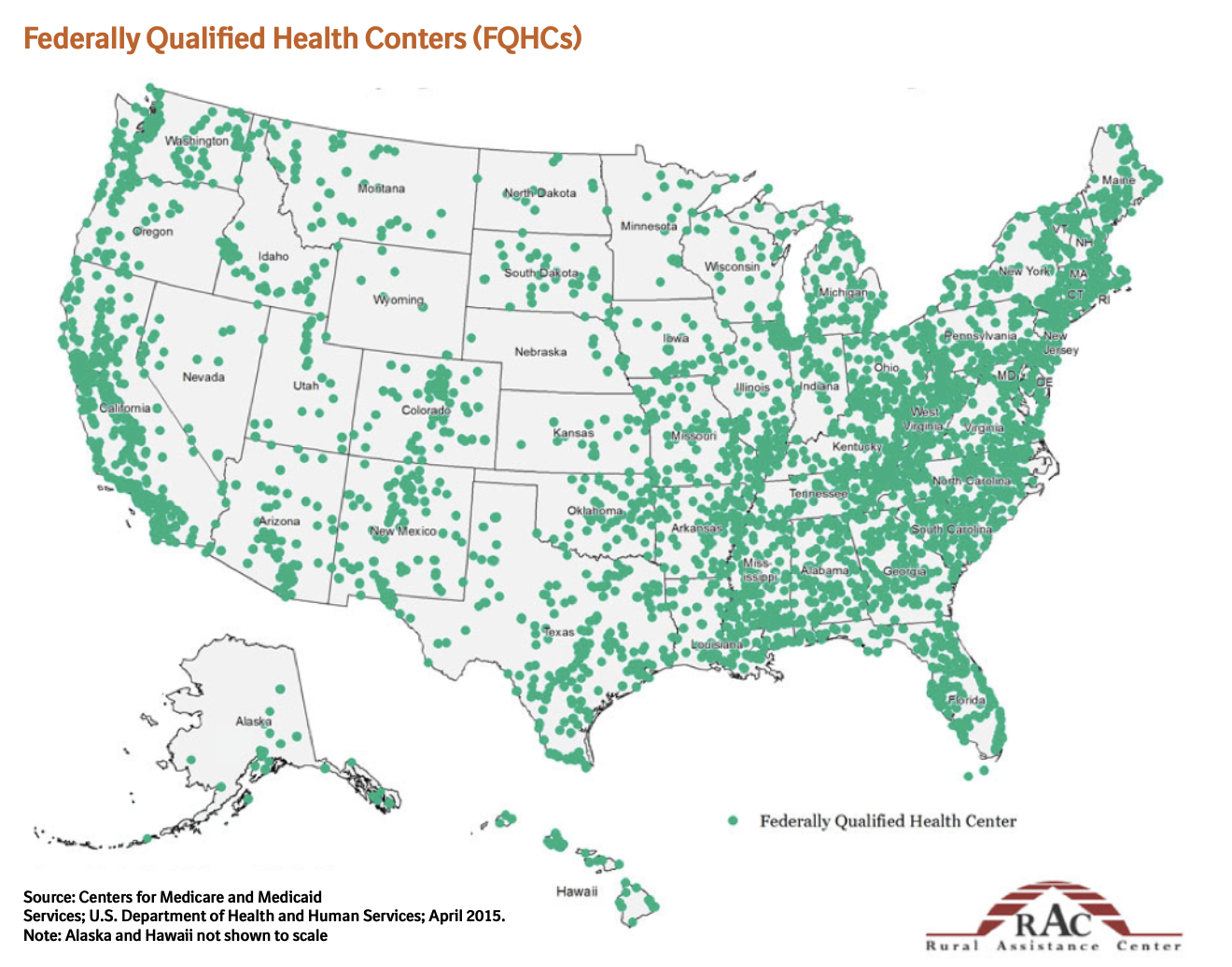

Efforts to correct some of these problems are a goal of the Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) program (figure 2).

Clinics located in underserved rural and urban areas and are funded by the federal government’s Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). As a result of receiving this designation, these clinics must see all patients, regardless of their ability to pay. After qualifying for this status, a clinic is able to apply to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to become a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC). Becoming an FQHC allows these clinics to become eligible for a variety of benefits, including better reimbursement. There are approximately 14,000 FQHCs in the United States, and every state has a number of centers. (Figure 2)

Many of them are located in rural communities. The federal government provided $6.7 billion to fund this program in 2022. Most physicians do not know about this program and have not participated in it.

Because of their funding streams, FQHCs are able to be located in areas where private practices may not be sustainable. Their grant funding and reimbursement provide support for infrastructure, personnel, building maintenance, equipment, and facilities adequate to evaluate and treat outpatients. The FQHC program was added as a US Government Medicare benefit in 1991, and this program has been a literal lifesaver for patients in medically underserved areas.

This program serves one in three people living in poverty in the United States, one in five living in rural communities, one in 9 children, and nearly 400,000 Veterans of military service.

In 2021, these clinics conducted more than 124 million visits, including 26.1 million virtual visits. A requirement of the FQHC program is the use of financial sliding scales. Each FQHC has its own set of sliding scales, but it is possible that if an individual is in the lowest tier of income, the cost of a new patient evaluation may be around $10, and prescriptions may be around $3. As a person’s income increases, the cost of care slides upward to relatively standard levels encountered elsewhere in the country.

A requirement of the HRSA Health Center program is that these clinics are required to have a Board of Directors who live or work in the community, and a majority must be patients of the center, to have cost evaluation programs in place, and to provide data on the effectiveness of care. Data indicate that these programs have been quite successful in providing a source of care for those in underserved areas who would otherwise not have access to this care. However, because their grant funding must be spent on primary care, these clinics generally lack the involvement of specialists and referrals to specialists are often constrained both by geographic and financial considerations.

Other programs needed to improve care for patients in rural communities

Provider support, increased educational opportunities utilizing technology, tailored interventions, and family support are vital clinical tools important to improving type 2 diabetes self-management in rural communities. Family support and involvement have also been shown to be a positive factor and important instrument and successful diabetes self-management, which minimizes disease and related distress.

Studies performed on the psychosocial impact of type 2 diabetes self-management among rural African-Americans found that one of the major contributing factors to their success was family support. Identification and acknowledgement of each individual’s perceptions about diabetes self-management, efforts to involve family members as supportive figures, and healthcare providers offering constructive support enhance the quality of diabetes management.

Implementation of guidelines

A key goal in managing patients with diabetes is to meet the guidelines for care established

by professional societies. Unfortunately, a limited number of primary care providers for patients in rural communities are not adequately implementing recommendations regarding diabetes self-management.

Data suggest that physicians do desire to address diabetes education and management for patients in rural communities but lack the resources to do so. The ADA and other national accreditation bodies provide evidence-based guidelines for the management and treatment of diabetes. Consistent adherence to such guidelines is critical if clinicians are to successfully manage diabetes, reduce comorbidities, and reduce complications.

Individual responsibility is important in diabetes care, but adequate support, proper use of provider tools, and education for patients and providers can enhance overall patient self- management and performance. Nonetheless, further research is needed in order to improve our understanding of barriers hindering type 2 diabetes self-management and the use of provider tools for self-management efficacy.

Potential solutions to the problems outlined

A key limitation of the FQHC program, especially in rural areas, is the lack of access to specialists. Although the FQHCs themselves provide high-quality primary care, they do not have the patient load necessary to support having specialists on staff. Similarly, the low population density makes it difficult for specialists to set up practices in rural locations. However, with the wide availability of telemedicine, it is now possible for specialists working in urban areas to consult on or co-manage patients at a distance.

The personnel working at the FQHCs can interact with the specialists to facilitate the ordering of medications and laboratory tests. Frequent follow-ups are possible either by telephone or television. The financial reward to the specialist can be through billing through his/her office or through payment by the FQHC.

Future goals for protecting patients in rural areas

This author’s six-year experience in co-managing patients with diabetes in FQHCs via telemedicine provides evidence that concurrent care with input from an endocrinologist can be beneficial for these patients. The future plan of the author is to recruit retired endocrinologists to utilize his template and set up collaborations with FQCHCs. If successful, this plan has the potential to benefit a large number of patients.

It is important to remember that knowledge and experience are too precious to waste!

To read and download the full eBook ‘Challenges to care of patients with diabetes in rural, undeserved areas’ click here