Rick Goodman, Food Allergy Research and Resource Programme at the University of Nebraska, discusses ongoing issues such as food security in the wake of COVID and economic crises

When it comes to COVID-19, the impact of the virus is seen in intricate, deep-rooted ways across the globe and outside of the death toll alone. Shadow pandemics, such as economic crises that impact the most vulnerable groups or mental health issues that afflict whole sectors, are emerging – even as the pandemic continues across most countries.

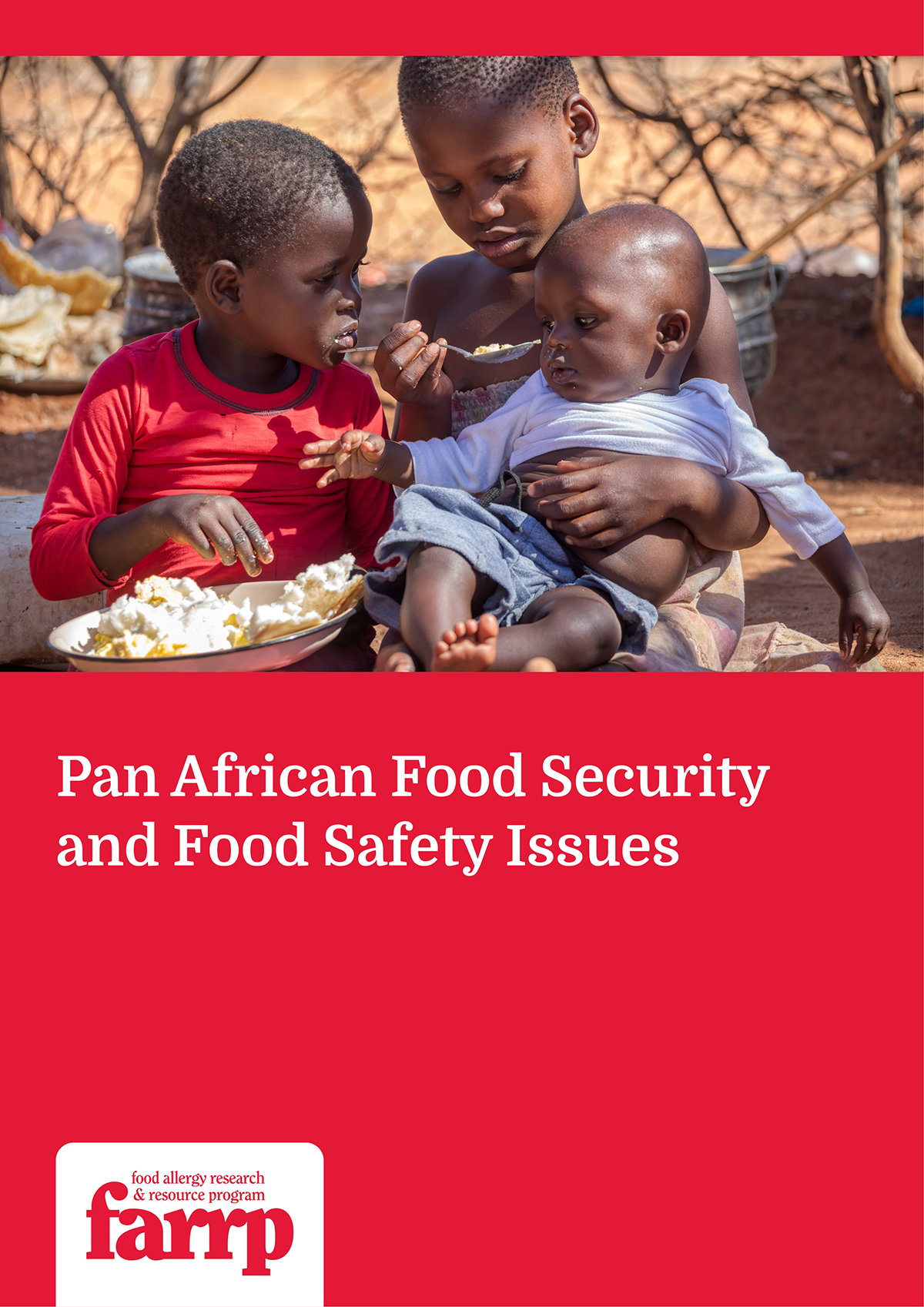

One key shadow pandemic that implicates thousands of people is increased food insecurity. Across the globe, those who already had risky relationships to a secure source of food have been forced to experience a worsening situation. But this problem has been an undercurrent in Africa since long before the virus hit – now it has simply come to the fore in an urgent way.

In 2019, 647,000 children younger than the age of five were considered severely malnourished in Somalia. The changing political situations in the region can also have a direct impact on who can access food, and who can grow it.

According to Goodman, agricultural output in Africa is not matching population growth. Right now, the population of Africa is roughly 1,362 billion, and growing by the day. Yet the production of food remains relatively low in sub-Saharan Africa, in contrast to other regions of the world. It is essential that no matter the political situation and the changing climate, local people can have secure access to food. When it comes to access, there are issues that Goodman identifies about the future of Pan African food security that could potentially be resolved.

If you want to understand what solutions exist for Pan African food security, read more about the work of the Food Allergy Research and Resource Programme at the University of Nebraska here.