Correctional leaders are confronted with implementing the goal of offender rehabilitation in the context of limited funding for treatment programs. The pursuit of rehabilitation and trauma healing is further impeded by rising mental health problems in jails and prisons

Consequently, there is a crucial need for effective and scalable interventions that help reform offenders and reduce recidivism in a cost-effective and replicable way. We offer an empirical assessment of a volunteer-led, small-group program of trauma healing for inmates housed at a regional jail in the United States. The program was administered by two faith-based, non-profit organizations that partnered to equip chaplains and volunteers to facilitate the program.

The elusiveness of offender rehabilitation

In general, there are four major goals associated with correctional policies and the supervision of incarcerated individuals: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation (Kifer et al., 2003). Among these goals, the public is particularly supportive of rehabilitation, especially when people are asked to rank the importance of rehabilitation versus punishment (Cullen et al., 2013; Johnson & Larson, 1997). Not only do a majority of Americans support the pursuit of offender rehabilitation, but there is also empirical evidence that effective rehabilitation programs can indeed reduce recidivism (Baker et al., 2015; Gannon et al., 2019; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007; Mitchell et al., 2007). At the same time, recidivism rates remain high (Alper et al., 2018), which is a constant reminder to policymakers that effective rehabilitation of incarcerated individuals continues to elude many correctional leaders.

There are many reasons why rehabilitation is difficult to achieve, but shrinking correctional budgets is likely at the top of the list. The failure to widely implement effective correctional treatment programs has often been met with the perception that correctional leaders oppose treatment in favor of more punitive approaches. The reality, however, is that wardens and correctional administrators overwhelmingly value the pursuit of rehabilitation. Still, they struggle with how to fund these approaches in the context of budget constraints (Cullen et al., 1993). The pursuit of rehabilitation is further exacerbated by the alarming rise of mental health problems in jails and prisons, the deleterious effects of unaddressed trauma experienced by most offenders in correctional facilities, and the shortage of volunteer-led programs and trained volunteers to staff existing rehabilitation programs.

Mental health problems in jails and prisons

In the early 1960s, states embarked on an initiative to reduce and close publicly operated mental health hospitals, a process that became known as deinstitutionalization. Advocates of deinstitutionalization argued that it would result in the mentally ill living more independently, with treatment provided by community mental health programs. The federal government, however, did not provide sufficient ongoing funding for community programs to meet the growing demand. As a result, many thousands of mentally ill persons were released into communities that were not prepared to meet their treatment needs, consistent with a report of the U.S. Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Consequently, many of the individuals released into the community without support ended up incarcerated in jails and prisons.

According to national surveys of the U.S. correctional population, 56% of state prisoners and 45% of federal prisoners experience mental health problems compared to 11% of adults in the general population (James & Glaze, 2006). The rates are higher among jail inmates (64%). Serious mental illness has become so prevalent in U.S. correctional facilities that jails and prisons have been referred to as “the new asylums” (Public Broadcasting System, 2005). Moreover, about 20% of inmates in jails and state prisons are estimated to have a serious mental illness (Gonzalez & Connell, 2014; Steadman et al., 2009). According to this estimate, in 2014, about 383,000 individuals with severe psychiatric diseases were behind bars in the U.S.

Because of their impaired thinking, many inmates with serious mental illnesses present behavioral problems, and this is a contributing factor to their over-representation in solitary confinement. Relatedly, suicide continues to be a tragic problem within the correctional system. In fact, suicide is the leading cause of death in jails, and multiple studies indicate that as many as half of all inmate suicides are estimated to have been committed by those with serious mental illnesses (Carson & Cowhig, 2020).

Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder among incarcerated individuals

Adding to the problem of mental illness is the fact that trauma exposure and trauma-related symptoms are prevalent among incarcerated individuals. For example, studying a random sample of adult males in a high-security prison, Wolff et al. (2014) found rates of current post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and lifetime PTSD to be 10 times higher among male prisoners than rates found in the general male population. Moreover, lifetime rates of trauma and PTSD are known to be associated with psychiatric disorders (Gobin et al., 2015).

Various types of potentially traumatic events (PTEs) occur throughout the life course, including child or adult sexual abuse, physical abuse or neglect in childhood, nonsexual assault, emotional abuse, witnessing violent death or injury (including criminal victimization), disaster or fire, and accidents. Research shows that offenders in jail and prison tend to report significantly higher rates of PTEs than those in the general population. For example, one study found that jail inmates were 7.5 to 11.3 times more likely to have a history of homelessness than those in the general U.S. adult population (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2008).

According to a study of male inmates in a New York State prison, the prevalence of childhood victimization by physical or sexual abuse and neglect was as high as 68.4% (Weeks & Widom, 1998). In a study of female parolees from five prisons in California, Messian and Grella (2006) found that the prevalence of childhood traumatic events was higher among female offenders than women in a comparison sample from a health maintenance organization in a metropolitan area.

Not surprisingly, experiencing PTEs has been linked with poor physical health, substance abuse, and psychiatric disorders including PTSD, depressed mood, and suicidality among offenders (Gibson et al., 1999). These are all significant social and public health problems that reduce the likelihood of rehabilitation of offenders, as well as their successful reintegration back into society. Unless healing from trauma becomes a priority, offender rehabilitation will continue to remain an elusive goal, as will the problem of societal reintegration.

In sum, incarcerated individuals are much more likely than the general population to have serious mental illnesses, and a substantial portion of the correctional population is not receiving treatment for mental health conditions. This problem has the potential to affect not only inmate health and safety during incarceration but also recidivism, as it hinders any efforts for rehabilitation before release. Moreover, despite the fact that trauma-associated mental health problems are more prevalent among inmates in jails than prisons, jail inmates remain even less likely to receive treatment than state and federal prisoners (Chari et al., 2016; James & Glaze, 2006). This problem is exacerbated by the transient nature of jails (Gonzalez & Connell, 2014; Zeng, 2020).

In this context, we conducted a quasi-experimental study to assess the effectiveness of a short-term, volunteer-led program for trauma healing among jail inmates.

Assessing a faith-based program for trauma healing

We examined the effectiveness of the Correctional Trauma Healing Program (CTHP) of the American Bible Society (ABS), a volunteer-led program for inmates housed at the Riverside Regional Jail in North Prince George, Virginia, which is supported by Good News Jail & Prison Ministry (Good News). Founded in 1816, ABS is a U.S.-based non-denominational Bible society that publishes, translates, and distributes the Bible. Good News places Christian chaplains in jails and prisons to minister to the spiritual needs of inmates as well as correctional staff. This ministry believes that the most effective tool for meeting the needs of inmates and staff is the daily presence of a chaplain. The chaplain serves as a pastor, counselor, mentor, and friend to those behind bars. Although correctional chaplaincy has existed for many decades in federal and state prisons, on-site chaplains were virtually non-existent in jails in the 1960s, and Good News was, in part, launched to remedy this oversight.

Correctional Trauma Healing Program (CTHP)

The ABS and Good News partnership relies upon the book, Healing the Wounded Heart: An Inmate Journal, and adjoining program model. Chaplains and volunteers deliver the program in 29 states. The Bible is a central component of the program, which is grounded in Scripture-based stories and examples. Here is a description of the program:

This unique method of trauma healing unites proven mental health practices and engagement with God through the Bible. Trained facilitators empower participants to identify their pain, share their suffering, forgive their oppressors, and bring their pain to the cross of Christ for healing. As they release their pain, they are often able to forgive and sometimes can be reconciled with those who have inflicted the pain. They are freed to care for themselves and serve others. Healing the Wounded Heart, ABS’s contextualization of the program for those in correctional ministry, contains a set of practical lessons that lead incarcerated people and those transitioning back to their communities, on a journey of healing.

In the current study, the CTHP was offered throughout the jail facility in Virginia on a rotating basis ensuring that inmates of every security classification level (i.e., minimum, medium, and maximum) and all housing units (each of which consisted of five “Pods” with a capacity of 60 to 90 inmates each) had access to the program. On average, two healing groups were offered monthly, one for females and another for males. About a week before the start of each group, a flyer about a recruitment day was posted, and a verbal announcement was made inviting interested inmates to attend a presentation explaining the program and how they could benefit from it. After the presentation, questions were answered, and inmates expressing interest were given an application/commitment form. About three days before a group started, chosen inmates and alternates were confirmed their acceptance into the program, and were also offered the opportunity to participate in survey research related to the program.

The CTHP was implemented primarily by Good News volunteers at the jail who sought out training to meet the mental and spiritual needs of inmates. Volunteers interested in helping others in this Bible-based trauma healing program attended an equipping session. This session invited them to (a) experience the program themselves, explore the trauma they may be carrying, and bring it to Christ for healing; (b) experience and practice participatory learning; and (c) learn basic biblical and mental health best practices. Then, they developed their own plans for using the material in their facility. At the end of the training, they were given feedback on whether they could continue in the process. Those who were certified to continue returned to their communities to apply what they had learned through a practicum. During the practicum period, they facilitated the five lessons of Healing the Wounded Heart at least two times and to a minimum of three people. After the practicum, they attended an advanced equipping session, which enabled them to hone skills, receive more feedback, and provide care for traumatized individuals.

Research questions

This study addresses four interrelated questions:

- Does the Correctional Trauma Healing Program (CTHP) work?

- In other words, is the CTHP an effective treatment intervention that helps incarcerated individuals who have previously experienced traumatic events cope with the negative consequences of their trauma? For example, do inmates with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) report a reduction in PTSD symptoms after completing the program?

- How does the program work? Stated differently, if the CTHP works, why is it effective and what are the mechanisms that promote healing from trauma?

- Moreover, what are the anticipated outcomes of the CTHP that are likely to help victims cope with trauma consequences in prosocial or positive ways? For example, after completing the CTHP, are participants more forgiving and less vengeful toward a person who caused a traumatic event than before? Does the program help the participants become resilient or regain a sense of meaning in life that they may have lost as a result of trauma?

- Does the impact of the CTHP last?

- That is, if the program is effective, how long does the impact of this intervention last? This is an important question since the effect of certain programs – especially those of short duration, like CTHP – may be short-lived, disappearing relatively soon after a program has ended. Relatedly, correctional decision-makers need to know not only if the negative consequences of trauma are reduced after the program, but also whether they remain at a reduced level for a given period or soon return to the previous level. For example, if PTSD decreases after the program, does that reduction hold for a month or even longer after completing the CTHP?

- Is the observed pattern of reduction in trauma consequences attributable to the pattern of the program’s outcomes?

- In other words, regardless of how long the impact lasts, are changes in trauma consequences over time after the program attributable to changes in the program’s outcomes? This is a longitudinal version of the second question. For example, if the level of PTSD symptomology decreases after participation in the CTHP, is the effect likely due to increased forgiveness or resilience among CTHP participants?

Methodology

To address these questions, the American Bible Society awarded a research grant to Baylor University’s Program on Prosocial Behavior at the Institute for Studies of Religion. Our subsequent research relied upon a longitudinal survey that was conducted from September 2018 to March 2020 at the Riverside Regional Jail in Prince George County, Virginia (Johnson et al., 2021; see Appendix A for details). The following summary provides a brief description of the research design and analytic strategy as well as demographic profile of the sample (Johnson et al., 2021: see Tables A1 and A2):

- The survey was conducted with a sample of 349 inmates (178 males and 171 females).

- The total sample consists of a treatment group of 210 inmates (106 males and 104 females) who participated in the CTHP, and a control group of 139 inmates (72 males and 67 females) who did not participate.

- The program was run in small groups, each of which began with, on average, 12 inmates.

- The treatment group was comprised of 22 healing groups (10 male and 12 female groups), each of which completed four surveys: a pretest (before the program started), a posttest (soon after the program ended), and two follow-ups (approximately one and three months after completing the CTHP).

- The control group was created based on a random sampling of inmates who did not sign up for the CTHP and participated in two surveys: a “pretest” and a “posttest,” with a two-week interval.

- The study participants were, on average, about 38 year sold, with the youngest and oldest being 18 and 65, respectively. The sample was split almost equally between two race groups: 48% white and 52% black.

- About eight out of 10 (79%) study participants were single, and 85% reported a religious affiliation: 72% Christian (61% Protestant, 11% Catholic), 9% Muslim, 1% Jewish, 3% other religion, and about 15% no religion.

- One third (34%) of the participating inmates were pre-trial detainees. The most common charge was a technical violation of probation or parole (65% of the sample), but some were charged with violent (28%), property (36%), and drug offenses (26%) as well.

- More than eight out of 10 (86%) inmates had experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, and, importantly, the treatment and control groups did not significantly differ in terms of the average number of traumatic events experienced (i.e., about 3 events each).

- Approximately 70% of the sample was screened as PTSD positive, with treatment group inmates (72%) being more likely to be positive for PTSD than their control group counterparts (61%).

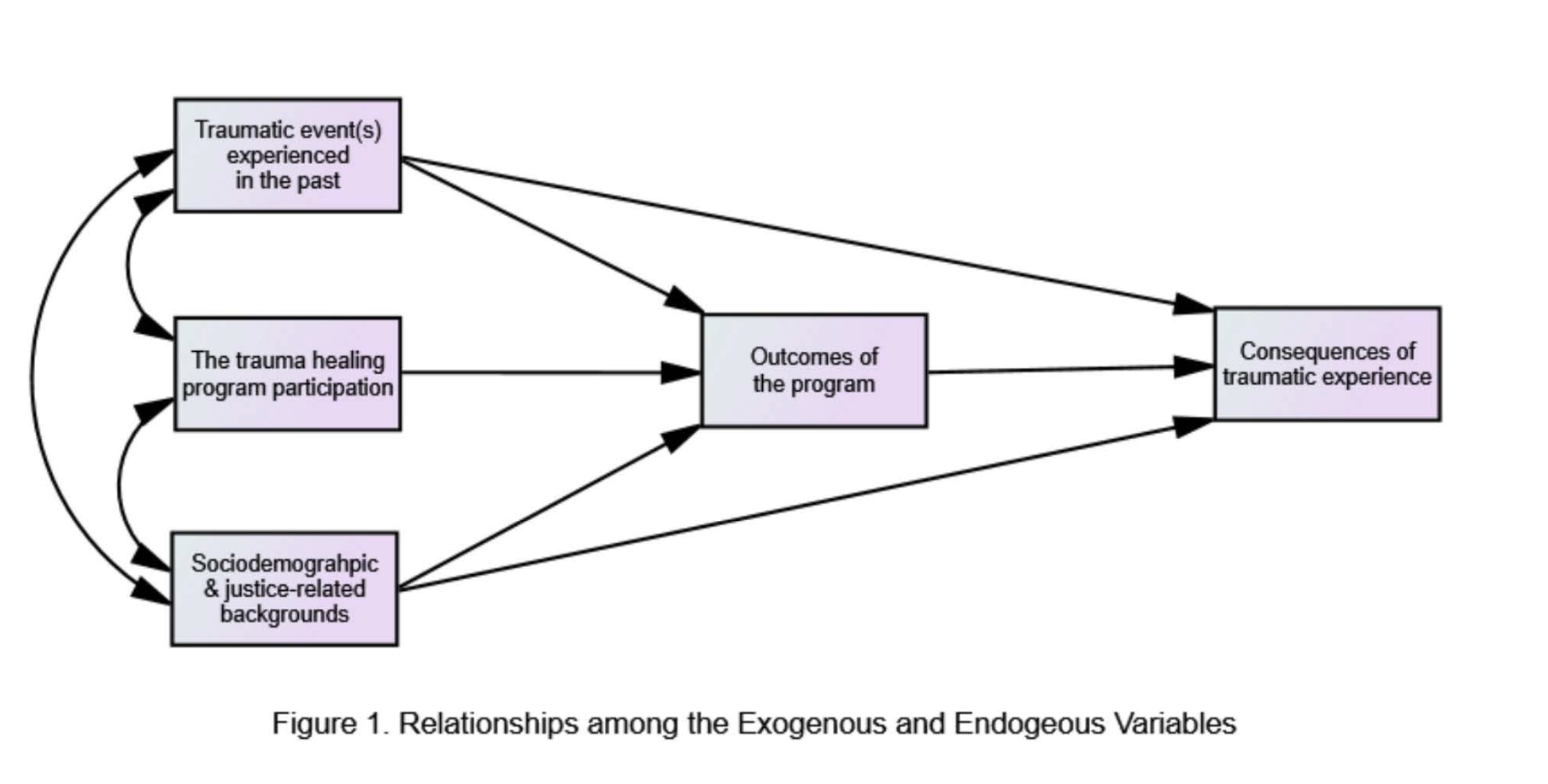

The survey included items measuring a variety of concepts (e.g., PTSD symptoms, depressed mood, depressed malaise, suicide, interpersonal aggression, etc.), mostly using multi-item scales (Johnson et al., 2021; see Appendix B for the actual survey). Information on sociodemographic and criminal justice-related backgrounds came from official data provided by the Riverside Regional Jail. The following three groups of concepts/ variables were included in analysis (see Figure 1 for relationships among the three groups of variables):

- Sociodemographic, criminal justice-related, and trauma exposure backgrounds (exogenous variables): age, sex, race, marital status, religious affiliation, number of admissions to jail, security classification, types of offenses committed, etc.

- Outcomes of the CTHP (mediating endogenous variables): forgiveness, resilience, religiosity, perceived social support, a sense of meaning in life, Bible impact, etc.

- Consequences of trauma (ultimate endogenous variables): PTSD, complicated grief, negative emotional states (depressed mood, depressed malaise, and anger), suicidal ideation, and intended aggression (the self-reported risk of interpersonal aggression)

For scale construction, the validity and reliability of survey items were examined based on factor analyses and inter-item reliability scores before combining items into composite measures by averaging or summing them. All scales had good to excellent measurement quality across surveys (Johnson et al., 2021; see Table A3).

The data were analyzed using various statistical methods to answer the research questions: one-way and two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), structural equation modeling, and random-effects models. All of the results summarized below are statistically significant at the level of .05 or less unless noted otherwise. Complete results from all of the analyses conducted are available in a separate document (Johnson et al., 2021; see appendices).