Efficient public warning systems save lives. Their efficacy has been highlighted in recent events across the world and is proven to be the difference between swift evacuations or fatal outcomes in the face of disasters.

Here, George Karagiannis, Risk and Resilience Program Director at Resilience Rising, explains why strong early warning systems need to be established in every country and how telecommunications are playing an increasingly significant role in navigating natural hazards

Climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of natural hazards, causing disasters to affect more people across the world. When a disaster occurs or is about to occur, one of the most important things to do is warn the affected population about any impending hazard or actual disaster.

Warnings provide vital information to the population and allow people to take protective action.

Risk to life: A direct correlation

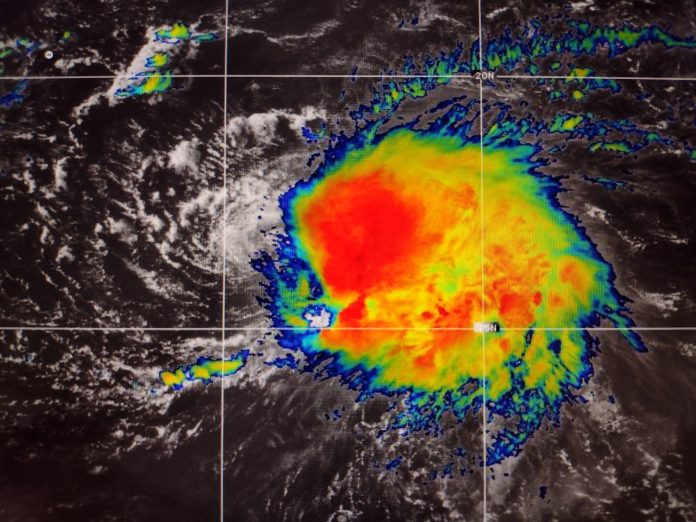

Implementing early warning systems is the first step. In February 2023, Cyclone Freddy hit Mozambique twice over the course of five weeks and became the longest-lived cyclone in recorded history. (1)

Communities across the country, including in Inhambane Province in the south, received warning of the impact through mobile brigades, radio and megaphone announcements, days before Cyclone Freddy hit. Thanks to this, new, locally-centred early warning systems helped communities reach safety early and mitigate the fallout of such a huge natural hazard.

Much as the availability of public warning systems saves lives, the lack of these capabilities has been associated with many preventable disaster deaths. For instance, a fairly small brush fire claimed 104 lives in the seaside community of Mati, Greece in July 2018. Strong winds coupled with dry vegetation caused the fire to spread quickly to the residential area by the waterfront, destroying about 1,200 buildings in the process.

People were burned in their cars as they attempted to flee, while hundreds of people escaped to nearby seaside cliffs, hiked down to the beach, and were evacuated hours later from the water. In the absence of public warning capabilities, people self-evacuated when flames were hundreds of feet away or at the encouragement of neighbours.

Stagnant change

Despite being widely acclaimed for saving lives, early warning systems are still not available where they are needed most. About 70% of climate-related deaths in the last 50 years were in the least developed countries, and 91% in the developing world. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction estimates that as few as 24 hours of warning of an impending storm or heat wave can reduce the losses incurred by 30%.

Yet, multi-hazard early warning systems exist in only about 40% of the least developed countries and small island developing states. Globally, the number of countries reporting having such capabilities has almost doubled from 50 in 2015 to 101 in 2023, with a lot of improvement made in the last decade in Africa, Asia and the Pacific. However, coverage remains well below 50% in the Americas and the Caribbean, and significant gaps persist in Africa. Notwithstanding the relatively good coverage of dissemination technologies, public warning is often identified as a persistent gap and disaster preparedness remains one of the most problematic areas (2).

Preparedness saves lives

On August 8, 2023, fires broke out in different parts of Maui, Hawaii. One of the fires destroyed the historic town of Lahaina and claimed 98 lives, becoming the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century. Although Maui is no stranger to vegetation fires, Lahaina was ravaged and the majority of its about 1,800 buildings completely burned. People sought refuge at sea, whereas others burned in their cars trying to evacuate (3,4).

As fires broke out, broadcast emergency messages and social media posts from the County of Maui provided updates, alerts and evacuation calls for some areas, but apparently not Lahaina, despite it being densely populated with limited escape routes. Confusing messaging and delayed evacuation alerts did not help. Sirens are an integral part of the islands’ warning capabilities but were not activated in the fire.

Mechanical sirens, such as the ones used in Hawaii, produce a single tone, alerting people of an impending hazard, but provide no information about the nature of the hazard, its severity and, most importantly, protective action guidance. Note that the system is referred to as all-hazard, including for wildfires, and claimed as the largest in the world.

To be effective, sirens need to be associated with a single clear protective action. In fact, Maui County had advised people that when a siren tone is heard other than a scheduled test, tune into local Radio/TV/Cable stations for emergency information and instructions by official authorities. If you are in a low-lying area near the coastline; evacuate to high grounds, inland, or vertically to the 4th floor and higher of a concrete building.”

In other words, Maui residents were given incomplete information – the reference to evacuating to high ground is likely for tsunami emergencies, yet there is no reference in the instructions to tsunamis. This confusing messaging is exactly what emergency managers are taught to avoid.

Emergency managers preparing crisis response plans need an understanding of the factors affecting which sources of information people consider to be the most trustworthy and which ones they would prefer to get warning information from. Global safety charity Lloyd’s Register Foundation surveyed more than 125,000 people across 121 countries in their latest World Risk Poll, powered by Gallup, to gather insight into what most affects people’s safety globally. When residents from Africa (including Eastern, Central/Western, Southern and Northern Africa), one of the regions with low warning system coverage, were asked who they trust to provide information about a disaster, the results varied by region. However, all regions ranked local news as their most trusted source of disaster information.

Over one-third (38%) of respondents in Southern Africa trusted local news through newspapers, television, or radio to provide disaster information. Nearly half (47%) of respondents from Northern and Eastern Africa also trusted local news to provide disaster information, similar to respondents in Central/Western Africa where 40% of respondents trusted local news. Significantly, over 10% of respondents in Eastern Africa and Central/Western Africa trusted social media to provide information about a disaster, with over 13% of respondents in Central/Western Africa stating they also trust local religious leaders as sources of disaster information.

Telecommunications: The future of early warning systems?

Public alert and warning systems are becoming an increasingly critical link in the process. These systems provide emergency information to the public, and save lives when disasters are about to strike. To be effective, warning messages need to be issued from credible and trusted sources, such as weather services, local authorities, and local media. Modern public alert and warning systems enable emergency management agencies to disseminate information through multiple pathways, including mobile and landline phones, radio, television, highway variable message signs and others.

Because of the inherent complexity in combining all those technologies, these systems should be tested to the limit of their abilities at regular intervals. In addition to the obvious maintenance benefit, these tests are opportunities for informing the public about the capabilities of alert and warning systems, as well as teaching individual and family self-protection in disasters. In the US, nationwide tests of the Emergency Alert System – which is based on radio and television, cable systems, satellite radio and television – and the Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system – delivering alerts from cellular towers to mobile devices using a one-to-many technology called Cell Broadcast (CB) – have been required every three years since 2015.

European Union countries have been legally required to put in place public alert and warning systems using location-based SMS or similar technologies no later than June 2022. Although such systems were already used in several European countries before that deadline, Greece was one of the first countries to use Cell Broadcast for wildfire evacuations. The country learned the lessons of the Mati catastrophe and rolled out the 112 Emergency Communications Service in 2020.

The new service integrates a unified, multi-agency public safety answering capability based on the European emergency number 1-1-2 with a nationwide integrated public alert and warning system. Other European countries have followed suit. For example, France, which operated a warning system based only on sirens, deployed a Cell Broadcast system in 2022. In the UK, the first nationwide test of the Emergency Alert system, which also uses Cell Broadcast, was conducted in 2023.

In short, public warning systems are lifesavers, but they need preparedness and planning to work. Global funding and legislation will help with physical infrastructure, but building trust and communication specific to individual communities can make or break early warning systems in the face of natural hazards.

Extra information

- For more information about Resilience Rising, please click here.

- For more information about Lloyd’s Register Foundation, please click here.

- For more information about the World Risk Poll, please click here.

References

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/09/11/early-warning-system-saves-lives-in-afe-mozambique

[2] UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction), and WMO (World Meteorological Organization), 2023. Global Status of Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems 2023. Geneva: UNDRR.

[3] https://www.wsj.com/articles/lahaina-and-the-fires-in-greece-firefighters-natural-disaster-evacuations-maui-emergency-hawaii-fa99f1c0

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/19/opinion/maui-wildfires-hawaii-sirens.html