Though electric cars are greener than those running on fossil fuels, they generate mass carbon emissions during production and remain predominantly inaccessible

The global carbon emission target, aiming to reduce greenhouse gases to 1.5 degrees Celsius, has continued to be emphasised by governments – especially in 2021’s COP26 summit – stressing the need for urgent action from international authorities.

Global governments have begun investing into electric cars, but this expensive and largely inaccessible green trend shouldn’t be held as the ideal carbon-reduced commodity.

One of the strategies to implement change on a local level has been the generation of electric vehicles – yet research finds, this implementation hasn’t been very local after all.

If electric vehicles don’t use fossil fuels, how do they generate a carbon footprint?

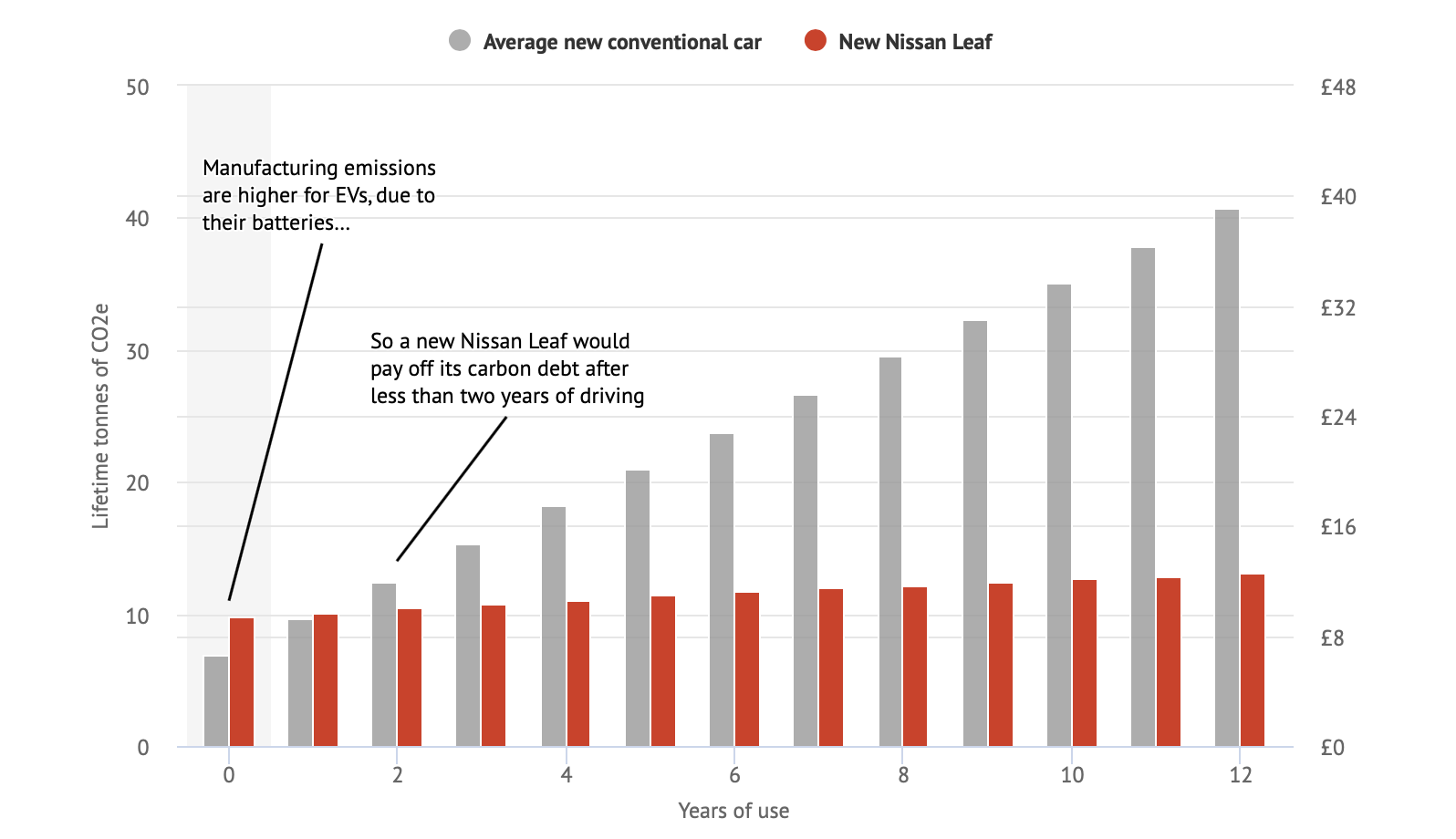

Considering the entire life cycle of electric vehicles, consumers must note the carbon footprint developed during the production, shipping, and battery generation of the cars before committing to an electric car.

Though no greenhouse gas emissions directly come from electric cars, they do still rely on electricity that is, largely, produced from fossil fuels in many different parts of the world where it is shipped to be manufactured.

The vehicle and the battery of the cars require copious amounts of energy to run.

Overall, electric cars will not be the ultimate saviour tactic to reduce emissions locally. As reported by C40 Cities, public transportation use in cities must double by 2030 for the world to meet its 1.5-degree target.

“We can’t slash climate emissions at the pace required without reducing the number of solo trips”

Aiming for an affordable, accessible, safe mode of transportation, electric car guidelines and future requirements set by governments are at risk of shifting the responsibility of lessening emissions from the government to the people.

60% of potential electric car buyers feel that there need to be better incentives like tax rebates

Though electric vehicles are rapidly growing with popularity – almost doubling in demand since 2021 – reports reveal that the UK alone will need at least £16.7 billion to get public charging networks ready for mass electric vehicle markets. The UK would need to build 507 new charge points every day until 2035, to improve buyer confidence.

Consumers are becoming increasingly expected to afford and utilise electric cars over the traditional diesel design, which will theoretically be banned from the market by 2030 in line with carbon emission goals.

A survey by SMMT finds that 52% of potential buyers avoid the switch due to higher costs of driving electric cars, 44% worry about the lack of local charging points, and 38% fear of being caught short on longer journeys.

While of 37% potential consumers remain optimistic about buying a full EV by 2025, 44% don’t think they’ll be ready by 2035 – with 24% saying that they can’t ever see themselves owning one due to all the aforementioned factors which come with electric car ownership.

SMMT also found features which drivers were the most attracted to: The lower running costs (41%) and chance to improve the environment (29%). Yet while these cars now account for one in six models on sale (17%), they still only make up just one in 13 purchases (8%), emphasising their inaccessibility.

Additionally, the carbon footprint of electric cars, once manufactured, depend on where they are. For instance, countries which generate electricity from predominantly renewable sources (such as Paraguay or Iceland), charging electric cars from the mains will have a much lower carbon footprint.

Adversely, countries that have high usage of coal in generating their electricity, the carbon emissions from using electric cars would be much higher, and in some cases actually exceed that of petrol and diesel vehicles.

However, as technology progresses, the batteries of the new cars will become increasingly longer and may have a second life as domestic storage batteries – reducing the overall environmental impact.

Temperature variations effect the functionality of electrical cars

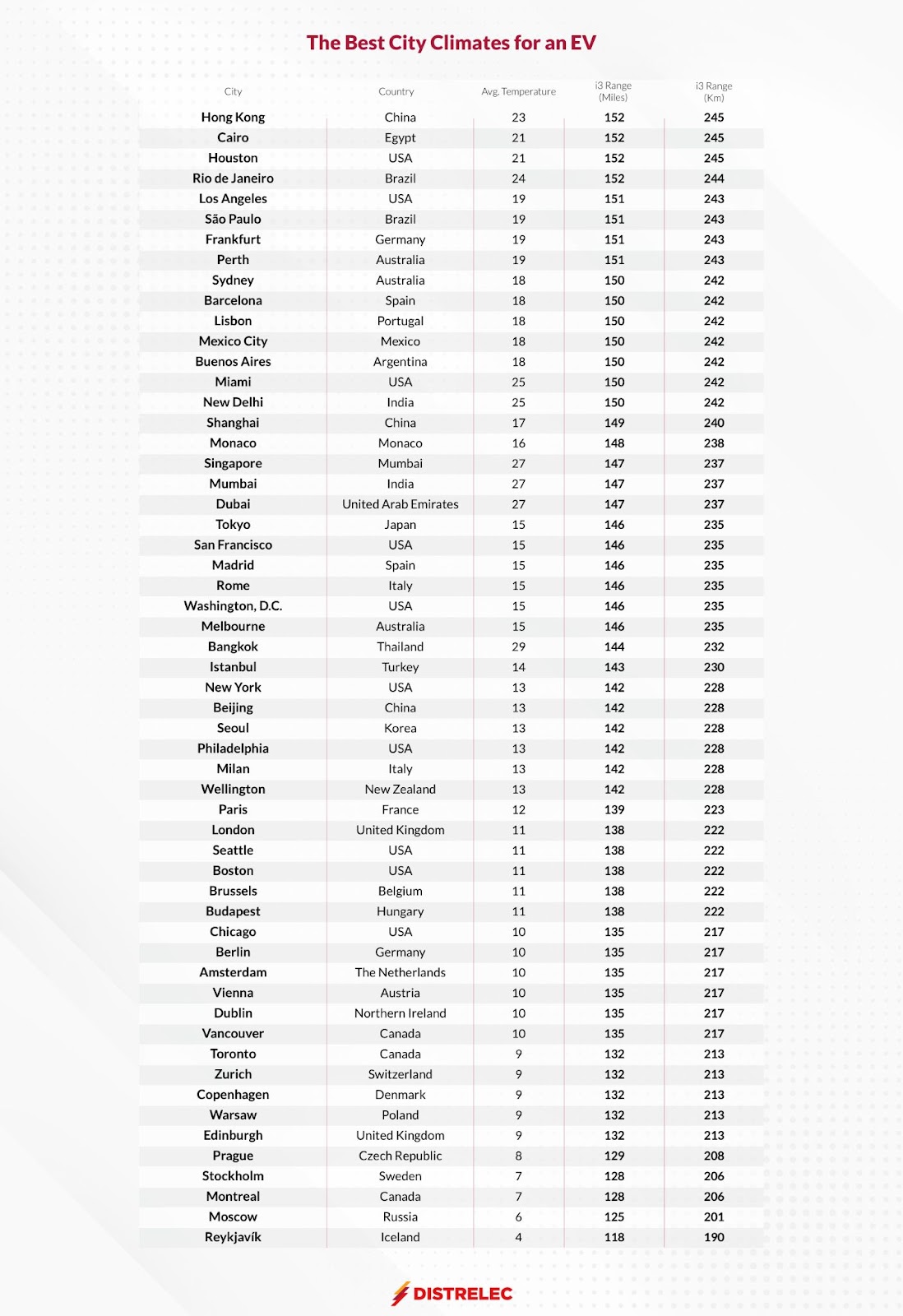

Data from Distrelec reveals that the ideal climate is 21°C for an EV, to get the highest number of miles out of a single charge; meaning that Hong Kong, Cairo, Houston and Rio de Janeiro all maintain the perfect average temperature to achieve a peak mileage of 152 miles.

At the top of the scale, Rio’s average temperature is 24°C. With anything higher than this, and the mile count begins to deplete more rapidly. As seen with countries with colder weather, such as Canada, Poland, Russia, Iceland and the UK, there can also be adverse effects on electric cars.

Reykjavík’s average yearly temperature is just 4°C, which reportedly loses residents an average of 34 miles from a full charge in comparison to those within the optimal temperature bracket.

The UK’s change to the Homecharge government scheme

Another issue with the UK’s adoption of electric cars is the lack of funding. This includes the lack of funding provided to charging ports, small businesses which rely on transportation, and other issues which revolve around the infrastructure which electric cars require.

The government began the OLEV Grant, or the Electric Vehicle Homecharge Scheme, which entitled homeowners to money from owning specific low emission vehicles and electric charger installation. This would theoretically help to meet the government’s ambitious net zero emissions target by 2050.

This grant covers up to £350 of the costs associated with installing a home electric vehicle charging point. However, this announcement came with hindrances – as political leaders allocated a specific amount of money to this grant scheme, which has now come to an end.

Though there are some requirements which still allow some buyers the OLEV grants, the government are going to scrap home-charging OLEV grants from 31 March 2022. According to experts, there are not enough funds to keep the scheme going across the country.

Should electric cars continue to be advocated by the government to be for the public good, local governments would have to pay for charging points in areas where demand is too low to offer healthy profits.

While local authority budgets remain as tight as they currently are, why is the UK not doing more to improve existing transportation?

Is it time for the UK to invest into public transportation?

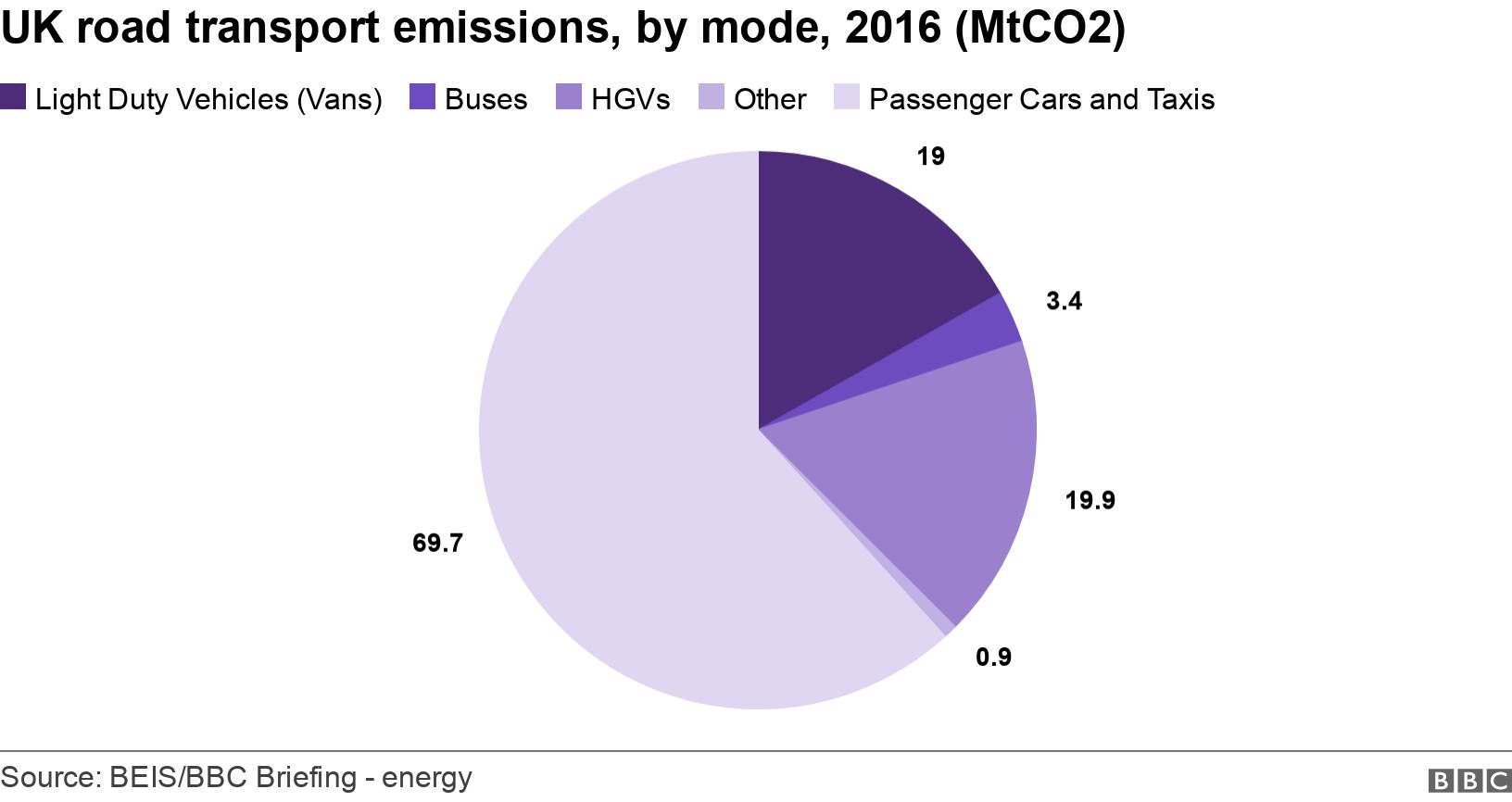

The UK has increasingly focused on electric cars but decreasing diesel and gas cars can’t be the only goal: they also need to increase public transit use. Transportation is responsible for about a quarter of all global CO2 emissions, from fossil fuel combustion.

Distrelec finds that doubling public transit use by 2030 would create 4.6 million new jobs in the 97 C40 member cities alone, and tens of millions of jobs around the world, according to that research. It would also cut urban transport emissions by more than half and reduce transportation pollution up to 45%.

Their survey revealed that only 42% of the surveyed would be willing to invest in an EV, with 40% of the same group also believing that having an EV would not help air and climate pollution.

Yet 70% of drivers stated that they would like more variety for plug-in models, including SUVs, minivans and sedans, which would benefit businesses which rely on everyday transport.

Comparing prices for diesel and e-vans, it can be considerably more expensive to lease an electric version of a popular van, than a diesel one, insinuating that electric vans remain unaffordable and inaccessible for many small businesses and self-employed delivery drivers until they become more available and cheaper.

Though there is more choice for those looking for an electric car, electric cars are still predominantly aimed at the higher end of the market, where minimal completely electric models are available for less than £20,000. Right now, buying a new Tesla Model 3 costs about £37,000.

FOI finds UK local authorities lack the money for an EV transition

Centrica found that local authorities in the UK will play host to just 35 on-street electric car chargers on average by 2025. However, councils broadly cited funding constraints, rather than a lack of mandate from governments, as their biggest challenge in switching to electric vehicles.

An FOI request by the Guardian in 2019 also found significant funding issues. In over 300 councils, some 100 said they had no confirmed plans to install more charging points due to financial constraints.

A Policy Exchange report in February that the UK’s annual charging point installation rate is currently just one-fifth of the levels needed to deliver the transition. Some 35,000 new points must be added annually through to 2030, the report stated, claiming that many local councils do not have the funding or in-house expertise to accelerate delivery.

Katherine Garcia, acting director of Sierra Club’s Clean Transportation for All campaign, said: “We can’t slash climate emissions at the pace required without reducing the number of solo trips. We absolutely need to increase investment in public transit. Public transit systems offer a sustainable and efficient way of moving through populated areas.”

Generally, it may be time to consider reducing emissions from the bottom up, focusing on the largest carbon emissions being reduced by improved and more affordable public transportation – with less focus on expecting consumers to make the environmental switch, without substantial support from the government.

References

https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/EV-life-cycle-GHG_ICCT-Briefing_09022018_vF.pdf

https://www.sierraclub.org/transportation

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-51977625

https://knowhow.distrelec.com/transportation/consumer-demand-survey-for-electric-vehicles/