Dr Becky Shu-Chen, Conservationist and Project Coordinator for China at the Zoological Society of London, explores the possibilities of positive human-wildlife coexistence, and how technology can be used to protect elephants

Human-wildlife conflict is one of the biggest challenges to the survival of the Endangered Asian elephant. Alongside other factors such as poaching and increasing pressures from climate change; habitat loss is driving the species into decline.

It is estimated that at the turn of the century there were more than 100,000 elephants in Asia (Santiapillai and Ramono 1992). The surviving population of Asian elephants is now estimated between 30,000–50,000, one-tenth of that of African elephants. As the human population rises, urbanisation and cleared spaces for agriculture increases. With this comes more occurrences of people and wildlife coming into contact, often with detrimental effects for both.

Coexistence is key to conservation

Living alongside large wildlife such as elephants can be difficult and at times, dangerous. No matter how well- meaning, the challenges associated with communities encountering wildlife is often misunderstood by those who aren’t on the front line. However, mitigating human-wildlife conflict is essential if we are going to be able to protect iconic species such as the Asian Elephants which not only have a place in our hearts, but play an important role in their wider ecosystems.

As part of my role at ZSL as Project Coordinator for China, I focus on people’s understanding of the increasing challenges that Asian elephants face. In 2021, a herd of fifteen wild Asian elephants in the south-west of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) made global headlines. They had left their nature reserve in Xishuangbanna, in Yunnan province, not far from the border with Myanmar and Laos, a year earlier. By early June, they had trekked more than 500 kilometres north to the outskirts of Yunnan’s capital city, Kunming, which is home to 8.4 million people.

During this time, I undertook an analysis of public perceptions using comments from Weibo- China’s largest social media platform. ‘Cute’, ‘gentle’, ‘intelligent’, and ‘human-like’ were the most popular reactions from people engaged with the daily reports of the herd’s progress.

While these reactions were encouraging, I was interested in the gap between general public understanding and the challenges on the ground. Elephants are often thought of as gentle giants. Undoubtedly wonders of nature, they have many endearing qualities such as close family units and clear emotional bonds. However, it must not be forgotten that they are wild animals. Often growing to four metres tall, weighing five tonnes, with an ability to run at twenty-five kilometres per hour — elephants can pose a threat to any unsuspecting person who crosses their path, particularly during a surprise encounter or while they have young with them.

In fact, during the infamous trek, some communities were left with vast damages of crops (approximately U.S. $1 million worth) and destroyed property and infrastructure. A rural communities’ reaction to damages like this can sometimes be met with blame from outsiders, but as the line between wildlife and people blur, we need to have a bigger discussion around what communities need to live alongside large wildlife and involve them in decision making on conservation efforts.

What do solutions look like?

ZSL works closely with communities in Kenya as well as across borders in India and Nepal to support positive human-wildlife coexistence, which includes working with governments and local wildlife agencies to support the improvement of livelihoods and well-being of people. This work is key to supporting vulnerable communities to find real benefits to conserving large species such as tigers in Nepal and India, and cheetah and wild dogs in Africa, which may otherwise pose a threat. For conservation to really work, local people need to be part of decision making and benefit from protecting the large wildlife that they live alongside.

With ecological, cultural, political, and historical diversity across nations, coexistence has no simple answer. The solutions are complex but research and past conservation success do point to the importance of protecting remaining wild habitats, reconnecting these wild places with ‘wildlife corridors’, education, and joined-up thinking between government, conservation groups and local people.

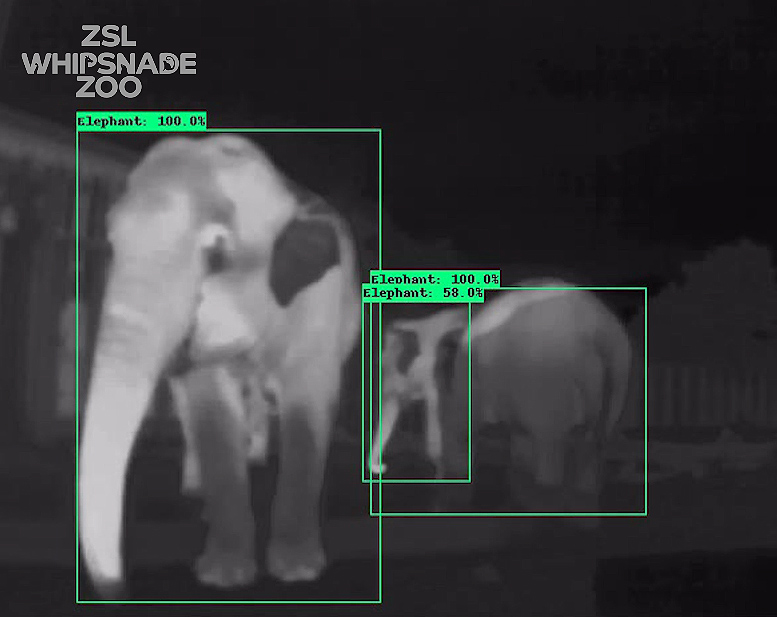

Technology can also be used to create effective change. The HEAT (Human-Elephant Alert Technologies) project is an early warning system tool that is currently being developed at ZSL Whipsnade Zoo. Camera systems that can detect elephants 24/7 use heat sensors to show the thermal shape of elephants (even in the dark). Once ready for launch, this technology could be used by communities to send an alert to people living around elephants so they can avoid any conflict situations.

More data is also needed. Human-wildlife conflict is compounded by fast-moving environmental changes. For example, amidst the global fascination with the elephants’ journey lies a sad truth. Their trek is a troubling sign of the poor health of the natural world.

Drought linked with climate change is one factor thought to have caused the elephants to make their journey, and with our current trajectory, it may not be the last time we see mass movement.

With movement of species comes a significant need for communicating the latest knowledge with those making decisions. The urgency to make sure that nature is at the heart of decision-making starts with understanding. Only when you understand the motivations and barriers for conservation actions can you make effective change.

ZSL is urging governments to put nature at the heart of policy-decision making, prioritise biodiversity loss and recognise its interconnections with other environmental issues such as climate change.

You can support ZSL global science and conservation work by donating at www.zsl.org.