Tim Broadhurst, CCO at CooperÖstlund Ltd, explores the financial and environmental benefits of considering CHP as part of a blended energy programme

The National Grid, a centralised system with an oligopoly of energy providers and a dated logistics network, is, arguably, no longer fit for purpose. Increasingly expensive to use, the UK’s commercial energy market has two uncompromising traits – inflexibility and unpredictability. For facilities managers in need of dependable supply and efficient overheads, finding a viable alternative is critical.

Centralised generation sees power created at scale and distributed through the National Grid. Purchased at variable rates and used by multiple end-users, it’s an expensive (and often unreliable) way to source your energy supply. Decentralised generation, on the other hand, such as combined heat and power (CHP), is a low-carbon solution to generate power on-site.

Effectively a gas power station, but more than twice as efficient, CHP combusts natural gas to generate electricity and thermal energy. The electricity can be used in place of the mains supply, while the heat can be used for space heating or to provide a continuous supply of hot water.

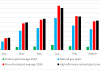

As gas prices are lower and more stable than mains electricity contracts, businesses can achieve significant cost savings by self-generating power (a payback period of less than five years, on average). Combined heat and power (CHP) technology, with typical efficiency levels exceeding 80%, can see operators save c.20% on energy bills and reduce their carbon emissions by, on average, some 30%. Transmission and distribution losses are reduced, while fuel supply security is maximised.

With energy supply at breaking point, centralised supply is crying out for decentralised support. As such, any excess energy generated through CHP operation can be sold to the National Grid – at a premium. Depending on the efficiency of the installation, natural gas supplied to the CHP and the resulting energy generated can be exempt from the main rates of the Climate Change Levy. Furthermore, as CHP offsets carbon, it can be used to meet Part L of the Building Regulations.

District heating and CHP

While the benefits of CHP as part of a blended energy programme are clear, its application within district heating has been relatively unpublicised. District heating is defined by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) as ‘a pipe network that allows centralised heat sources to be connected to many heat consumers’. It uses a network of insulated pipes to deliver heat, in the form of hot water or steam, from a centralised location to multiple end-users. In the UK, the Government’s 2018 Clean Growth Strategy confirmed its commitment to district heating, predicting that by 2050, 17 to 24% of UK heating will be supplied by district heating systems.

Small-scale district heating networks can be effectively powered with the heat created by CHP. While national systems, like those operational across Scandinavia, typically harness heat from the incineration of waste, on a smaller scale, it is perfectly possible to power apartment buildings, commercial properties and business parks with CHP-driven heat. Hotels, hospitals and nursing homes, for example, which consume huge amounts of energy, are ideal outlets. Furthermore, they will also benefit from the cost-efficient decentralised on-site power generation element.

CHP and the future of UK energy supply

At CooperOstlund, we believe a pioneering approach is needed to safeguard the security of energy supply for the future. Decentralised technology will play a driving role – whether on-site energy generation or as part of a district heating supply network. For the energy consumer, the benefits are clear – dependable, reliable, cost-effective, low-carbon supply. There’s a long way to go before the government’s 2050 predictions become a reality, but the start of the journey has well and truly begun.